The Ukraine Context for International Grievances

As alarming reports of the Russian military’s attacks on Ukraine’s civilian population splash across the pages of the world’s media, politicians and pundits have referred to the ongoing atrocities as “crimes against humanity” and “war crimes” while demanding an international trial for the perpetrators. But how realistic is it that Russian officials will face a tribunal for breaching international law in Ukraine?

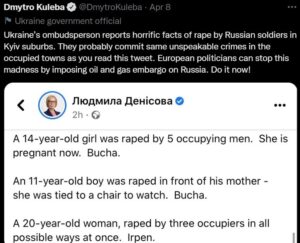

This month, in a Facebook post that was later shared on Twitter by the Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba, Ombudsman Ludmila Denisova alleged that Russian soldiers had attacked peaceful Ukrainian citizens, including “a 14-year-old girl was raped by five occupying men. She is now pregnant. Bucha; An 11-year-old boy was raped in front of his mother – she was tied to a chair. Bucha; A 20-year-old woman, raped by three occupiers in all possible ways at once. Irpin.”

Legal foundations

Sexual violence is not new to war, though “grave sexual violence” is one of the eleven “physical elements” that must be present for a crime to be classified as a “crime against humanity.”

According to the United Nations (UN), the 1998 Rome Statute, which established the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, Netherlands, a “crime against humanity” occurs “when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population,” with the conscious will, or knowledge of the actor and must have at least one “physical element” of “murder; extermination; enslavement; deportation or forcible transfer of population; imprisonment; torture; grave forms of sexual violence; persecution; enforced disappearance of persons; the crime of apartheid; [or] other inhumane acts.”

Similarly, the United Nations’ definition of “war crimes” includes all of the “physical elements” that may demonstrate “crimes against humanity”, but adds additional “physical elements” that are specific to warring nations, such as prohibiting crimes against prisoners of war (e.g., deprivation of due process, summary execution, etc.), crimes against laws of war (e.g., misusing the flag of surrender), or actions against the civilian population (e.g., using civilians as human shields, etc.).

If Ukraine “gets its day in court,” to prosecute Russians guilty of international crimes the most likely avenue would be via the ICC who is tasked with passing judgment on international cases relating to genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes of aggression.

Even though neither Russia nor Ukraine have ratified the ICC’s Rome Statute, Ukraine was granted jurisdiction at the ICC, in 2014, when Russia’s invasion first began, allowing for the judicial body to investigate alleged crimes committed by Russia within Ukrainian territory. Since the beginning of February’s hostilities, more than 40 countries have referred the situation in Ukraine to Karim Khan, the Prosecutor of the ICC.

To aid the investigation, Mr. Khan issued a statement in March indicating that the ICC had launched an online portal “through which any person that may hold information relevant to the Ukraine situation can contact our investigators.”

Mr. Khan’s statement went on to note that “if attacks are intentionally directed against the civilian population: that is a crime,” continuing that “there is no legal justification, there is no excuse, for attacks which are indiscriminate, or which are disproportionate in their effects on the civilian population.”

Laying the groundwork

The ICC has begun its investigation as to whether international law has been broken in Ukraine, however it will not be a straight-forward nor rapid process to hold accused Russian war criminals or human rights violators accountable.

Vasil Vovk, a retired Major-General of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) and lawyer, said that “today many people are talking about ‘genocide,’ which is the correct term to use, from a politico-military point of view,” and “now is the time to be doing the investigation.”

“The wisest course of action,” said Mr. Vovk, is to have the “Security Service of Ukraine, as it is within their jurisdiction, to register the crimes per Article 442 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (i.e. Genocide, that is an act committed with intent to destroy in whole or in part any national, ethnical, racial or religious group…)” which would give Ukrainian authorities the needed legal justification to investigate the crimes.

Simultaneously, a case should be launched per “Article 437 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (i.e., Planning, preparing, launching, or waging a war of aggression)” for which Ukraine must act quickly to “gather solid, admissible evidence” to be submitted in a future international trial, said Mr. Vovk.

Ukrainian authorities are now collecting evidence indicative of “war crimes” and “crimes against humanity” in the hopes that eventually this evidence will be used to prosecute the perpetrators at the international level, something that has gained greater attention after US President Joe Biden said this month that he believes that the Russian President is a “war criminal” and that “We have to get all the details [of the crimes] so this can be … a war crime trial.”

There is precedent of former national presidents being sent to The Hague (i.e. Slobodan Milosevic and Charles Taylor), but it remains improbable that a contemporary court in Russia would order their president’s legal immunity from prosecution stripped and his subsequent extradition to stand trial in an international criminal proceeding against him.

Assuming Russia does not extradite Mr. Putin, another option, albeit unlikely, would be that a country party to the ICC agreement takes the decision to act on an ICC-issued extradition warrant for Mr. Putin. However, making such a bold move would violate international law, and create a tremendous diplomatic scandal, as Mr. Putin travels on a diplomatic passport when he is outside of his country; thus, Mr. Putin is immune from arrest per the Geneva Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961.

Historically, Russia has shielded persons wanted for questioning by foreign governments in relation to crimes committed at the behest of the Russian state. Such was the case of Andrey Lugovoi, who allegedly traveled to London in 2006 to poison and kill former Russian spy Alexander Litvinenko, a personal enemy of Mr. Putin, with polonium-210.

British Government demands to interrogate Mr. Lugovoi were ignored by the Kremlin, and Mr. Putin orchestrated Mr. Lugovoi’s election to the Russian Parliament from Mr. Putin’s own political party, thus guaranteeing Mr. Lugovoi’s immunity and his issuance of a Russian diplomatic passport.

Another option, however unlikely, is that any country could unilaterally attempt to try Putin under the pretext of “universal jurisdiction,” a legal concept that some laws, such as human rights, are not limited by national borders and so any country can try those who are guilty of violating human rights. This theory has been put into practice by countries before, such as by Germany and Spain, but it is not likely that many countries would be willing to charge Russia’s head of state for human rights crimes in Ukraine.

In an interview with the Kyiv Post, Ukrainian MP Valentyn Nalyvaichenko, who formerly served as Ambassador to Belarus and as the head of the SBU in 2006 – 2010 and in 2014 – 2015, during which time Russia’s war on Ukraine first began, related that, “what we have seen – in Bucha, Irpin, and other cities – is that Putin, and his military, committed atrocities. More precisely, we should refer to these atrocities as ‘genocide.’ Why ‘genocide?’ Because the intention is to exterminate local people.”

Mr. Nalyvaichenko emphasized that none of the crimes taking place in Ukraine were mishaps, but the result of “careful Russian military planning – which further demonstrates intent, as required in order to prosecute international war crimes or human rights violations.”

As for what crimes Russian officials could be charged with, the former Ukrainian spy chief said “Where to start? The systemized bombing of civilian centers? The summary execution of civilians? The forced deportation of our citizens? The Russian soldiers’ disgusting torture and rape of Ukrainian women and children – simply because they were Ukrainian? An international court would have everything necessary to find the perpetrators of these heinous crimes guilty.”

Road to justice

Those interviewed agreed that Russia had violated international law in Ukraine but acknowledged that it would be an uphill battle for Ukraine to bring the perpetrators to justice in the near term.

Steve Nix, a Georgetown-educated lawyer who currently serves as the Eurasia Regional Director of the International Republican Institute (IRI) in Washington, D.C., indicated that “Vladimir Putin deserves the docket in the Hague or some variation of a Nuremberg Trial for the human rights violations in Ukraine.”

“The only way this can happen,” cautioned Mr. Nix, “is if there is an external demand to remand Putin to face justice,” something that would only be realistically acted on by a Russian court “if there is a transition of power in Russia” which he said was within the realm of possibility and “could very well happen.”

Sharing this view, Mr. Nalyvaichenko observed that since the situation in Russia is “perhaps more unstable than many realize, soon there could be substantial changes in Russia. Look at the total madness now – Putin is having FSB generals arrested. This could backfire on him.” However, Mr. Nalyvaichenko is certain that “this is not the same Russia that we knew before February 24,” and so there could be “yet unknown outcomes for Russia and its president.”

Mr. Putin’s problems will be compounded, says Mr. Nalyvaichenko, as the international community will not relent from its pressure to punish the wrongdoers. The eventual comeuppance must be “From the top-down: Putin and his cronies who planned and executed crimes against the people of Ukraine; Every General who disregarded and ordered violations of international law; Every soldier who committed raped. All of these crimes must be investigated until the very last man responsible for breaking international law is brought to face justice,” said Mr. Nalyvaichenko. To achieve these goals, Mr. Nalyvaichenko suggests that Ukraine sign multilateral agreements with other countries willing to assist Kyiv in investigating the crimes so that any future trials would be successfully prosecuted. Ukraine signed such agreements after Russian troops shot down Malaysian Airliner MH-17 over Ukraine in June 2014.

Darius Jurgelevičius, an international law expert and former diplomat who later served as the Deputy Director of the Lithuanian intelligence service, indicated that though presently Mr. Putin is quite securely installed in the Kremlin, there was no guarantee that Mr. Putin would be able to maintain power in the future.

“If Putin falls from power, the new Government may decide that by extraditing Putin, they are both reopening relations to the West while also getting-rid of their political opponent. Sending Putin to the Hague creates a win-win solution: They gain the West’s support while eliminating a political opponent. A new government could very well agree to extradite [Putin],” said Mr. Jurgelevičius.

Mr. Jurgelevičius added that after the war, an international donors’ conference would likely raise suitable sums to rebuild Ukraine, complimented by monies Ukraine would receive following an international court ruling that Russia was guilty of having launched an unprovoked attack on Ukraine.

“Undoubtedly, an international court will eventually find Russia guilty of starting this war, and will award restitution for damages to Ukraine,” said Dan Rapoport, a U.S. investment banker who spent nearly twenty years in Moscow before moving to Kyiv, where he is now participating in efforts to defend the city from Russian invasion. “Russian money and Russian Government money to rebuild” will cause a post-war boom for the beleaguered Ukrainian economy as “there is almost a trillion dollars of frozen Russian funds worldwide, including personal sanctioned funds and Central Bank funds. These funds will eventually be transferred to Ukraine as compensation after a court decision showing Russia’s culpability in the war.”

Mr. Jurgelevičius observed that one of the great inadequacies of international law today, as we see in the current situation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, is that Russia “never technically ‘declared war.’ By doing this, Russia sought to skirt international law as established in The Hague Conventions.” Moreover, “Russia loves to always cite that it is the successor of the Soviet Union, which is why it was given the USSR’s nuclear weapons, but it is not fulfilling the obligations deriving from the Helsinki Final Act of 1975, which was ratified by the Soviet Union, which guarantees the peaceful resolution of conflicts and the ‘peaceful change of borders.’” Mr. Jurgelevičius suggested that “Given this new reality, that a country like Russia thinks that the international law does not apply as they called their invasion of a sovereign country ‘a special military operation,’ instead of what it is – ‘a war’ – it is clear that we need to revisit international law so every country is clear that mincing, or playing with words, does not change the consequences for violating human rights or international conventions.”

Though the path to justice for Ukraine is complex, there is a consensus that Mr. Putin should not be sleeping too peacefully. When asked if Putin would realistically have a future court date in the Hague, an American legal lawyer working in the former Soviet States, who asked not to be named, said “Remember Russian history: Prior to 1917, when it was still not clear that the First World War was a disaster for Russia, few people were saying that the Tsar would soon fall. However, within a brief period of time, due largely to a disastrous war, the Tsar and his inner circle fell. Why should we think that Putin will not fall like his predecessor?”

For the victims of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the dream of seeing Mr. Putin stand before the world to answer for his crimes may yet become a reality.

Screenshot of Ludmila Denisova tweet on horrific brutality of Russian forces in Bucha