Billionaire Victor Pinchuk is Ukraine’s most renowned philanthropist, spending $125 million on many worthy causes. But no matter how much he tries to improve his reputation, few can forget how he made his fortune under the autocratic presidency of his father-in-law, Leonid Kuchma, or how some of his oligarchic ways persist even today.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of the Oligarch Watch series of reports supported by Objective Investigative Reporting Program, a MYMEDIA project funded by the Danish government. All articles in this series are available in English, Ukrainian and Russian. They may be published freely with credits to their source. Content is independent of the donor. Contact [email protected]

- Check out the freshest Ukraine news items as of today.

- Check out the freshest Ukraine news items as of today.

- Russian Losses in Ukraine War

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

A snapshot of Victor Pinchuk

Date of birth: Dec. 14, 1960.

Place of birth: Kyiv, but shortly after moved to Dnipropetrovsk

Wealth: $1.3 billion, fourth richest person in Ukraine, according to a 2016 estimate by Focus magazine.

Key Assets: Interpipe, a steel pipe and wheels manufacturer; Credit Dnipro Bank, ferroalloy plants; and his media empire, which includes ICTV, Novy Kanal, STB and, until recently, Fakty newspaper.

Personal: Married to Elena Pinchuk, the only daughter of former Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma. Three daughters; his eldest daughter is from his first marriage.

Praised for: Donating $125 million through his foundation to educational projects and scholarships, his annual Yalta European Strategy conference, Jewish causes and his art center in Kyiv.

Criticized for: Amassing wealth from insider deals when his father-in-law, Leonid Kuchma, was president; using his media arm to obstruct the investigation into the 2000 murder of journalist Georgiy Gongadze; his courtship of corrupt regimes, including the administration of overthrown President Viktor Yanukovych.

STORY AT A GLANCE

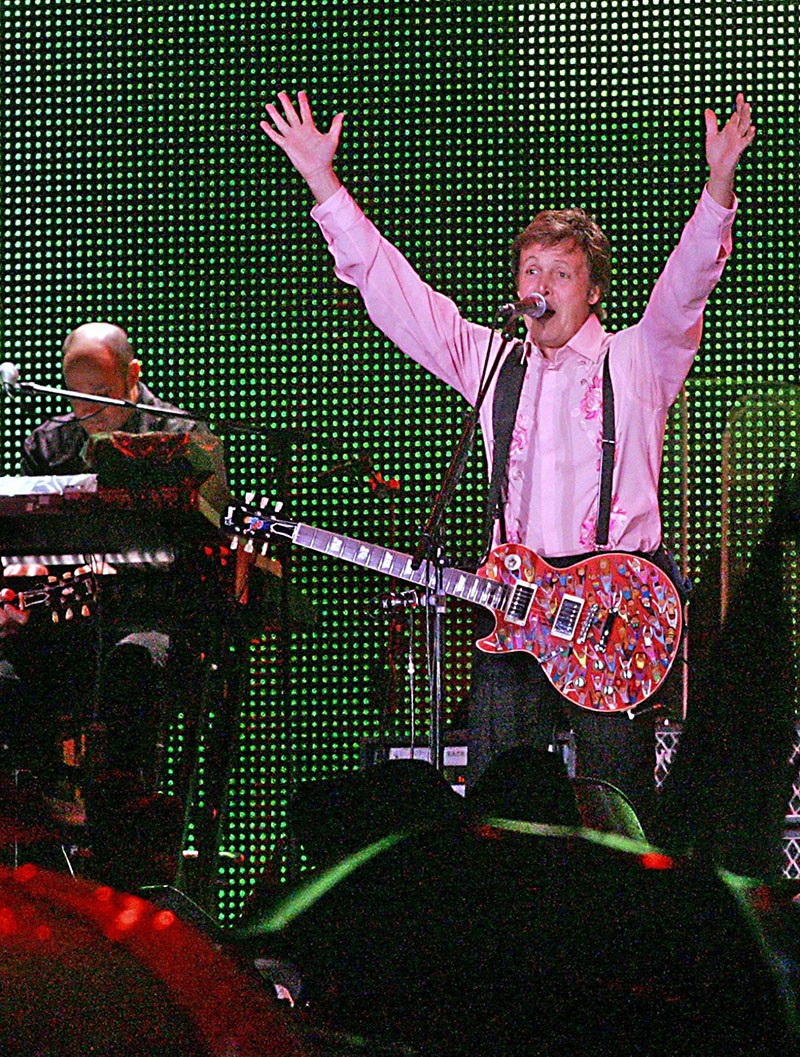

- Victor Pinchuk’s “friends” include Hillary and Bill Clinton, Tony Blair and Elton John. In paying millions of dollars in honorariums for famous politicians, entertainers, and business people to come to Ukraine, he has brought star power to Ukraine and raised the nation’s profile internationally.

- Pinchuk’s family includes wife Elena Kuchma, daughter of ex-President Leonid Kuchma. Pinchuk’s business empire was built via non-transparent tenders, mostly during Kuchma’s presidency between 1994 and 2005.

- Pinchuk helped Kuchma deflect blame for the Sept. 16, 2000, murder of journalist Georgiy Gongadze, exposed by the Mykola Melynchenko recordings, through his media holdings, including ICTV and Fakty newspaper.

- Other than fellow oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, with whom he has feuded, Pinchuk maintains working relationships with other oligarchs and top politicians, including Kuchma’s three successors – Viktor Yushchenko (2005-2010), Viktor Yanukovych (2010-2014) and incumbent Petro Poroshenko.

- Besides his well-publicized philanthropy, Pinchuk has luxury tastes in his personal life. The London Telegraph reported that Pinchuk spent $5 million for his opulent 50th birthday party in the French ski resort of Courchevel, flying in the Cirque de Soleil and superchef Alain Ducasse. Pinchuk also bought a top-end home in London at 17 Upper Phillimore Gardens, Kensington, for $120 million (at the time, Hr 1 billion) in 2008.

SEE ALSO:

New generations come to power with help from Pinchuk, one way or another, do they still owe him?

For this oligarch, owning 3 TV stations is way to help friends, warn enemies

STORY STARTS HERE:

In 2013, Ukrainian billionaire Victor Pinchuk welcomed current U.S. Democratic Party presidential nominee Hillary Clinton onto the stage at his Yalta European Strategy, an annual conference he funds to promote Ukraine’s European integration and strategy, calling her: “a real megastar.”

Clinton and her husband Bill, the 42nd U.S. president, have been paid speakers at the annual YES and other Pinchuk events. They describe themselves as friends of Pinchuk, who is known internationally as a businessman and philanthropist.

To date, Pinchuk’s charitable foundation has given $125 million to various causes, according to his spokespeople.

As well as the Clintons, Pinchuk can count Tony Blair, the former United Kingdom prime minister, and Elton John, the music legend, among his friends.

Billionaire Victor Pinchuk, founder the board of the Yalta European Strategy, introduces ex-U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in 2013. (Yalta European Strategy)

“Victor Pinchuk is the leading advocate for bringing his country into the European Union. He is heroic in his fight against anti-Semitism as well,” John once wrote. “Victor shows his love of our planet and makes the world a better place to live.” At the 2016 YES conference, actor Kevin Spacey made an appearance as Pinchuk’s special guest.

In April, Pinchuk was invited to join the international advisory board at the Atlantic Council, one of Washington’s best-known think tanks. Also on the board is former Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt, former U.S. national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, former U.S. Secretary of Defense Charles T. Hagel, and top business leaders.

“His efforts promoting Ukraine’s partnership with the European Union is matched by his unwavering commitment to promoting human rights in Ukraine,” Fred Kempe, president and CEO of the Atlantic Council, said in a statement about Pinchuk.

But Pinchuk hasn’t always mixed in such circles or received such praise. Pinchuk would not be interviewed for this story.

Moving to Kyiv

Pinchuk’s ascension to the top of Ukraine’s elite and into White House society began in 1990 with Interpipe, a Dnipropetrovsk steel pipe and wheel manufacturer that sold to countries in the former Soviet Union.

A pipe engineer by education, Pinchuk says he developed the business based on his own patents. At that time, Ukraine didn’t have a national currency, only the interim one known as the karbovanets, or coupons, so Pinchuk sold the steel pipes to Russia and central Asian countries in exchange for natural gas.

In the mid-1990s, he teamed up with Yulia Tymoshenko, then a Dnipropetrovsk-based gas and oil trader, to start a company called Sodruzhestvo.

“The then-governor (Pavlo) Lazarenko was also a beneficiary (of Sodruzhestvo). No one did anything without him in those days,” said Nikita Poturayev, Pinchuk’s de facto communications head in 1998. Pinchuk was first elected to parliament in 1998, serving as a lawmaker until 2006.

“But at some point Pinchuk understood that for him things could end badly, they might even kill him because they now knew how the scheme worked and they didn’t need him anymore,” Poturayev recalled. “So he started looking for connections in Kyiv. It took a while before he was in (then President Leonid) Kuchma’s circle though.”

According to Poturayev, Pinchuk was a classical music fan and funded several concert tours of famous Soviet orchestras to which he would invite members of the elite. It was at one of these concerts in 1996 that he was introduced to Kuchma’s only child, his daughter Elena. She became his second wife six years later.

Lazarenko fell from favor after challenging Kuchma for the presidency in 1999, fled and was subsequently arrested and later convicted in the United States on money laundering charges. Pinchuk took over his gas trade (as Lazarenko and Tymoshenko’s company, United Energy Systems of Ukraine, was excluded from the market) and became the top oligarch in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast through a series of privatizations, and the growth of Interpipe.

Victor Pinchuk remains a loyal son-in-law to Leonid Kuchma, Ukraine’s longest-serving president, in office from 1994 to 2005. (Volodymyr Petrov)

Jewish revival

Pinchuk helped a revival of the long-repressed Jewish community in Dnipropetrovsk led by Israeli-American rabbi Shmuel Kaminetzky, who arrived from Brooklyn in 1990. The Holocaust and World War II had almost wiped out the 100,000-strong pre-war Jewish community.

“From 1939 to 1990, there was no rabbi—there was some official communist-appointed rabbi, but no real Jewish life. They shut down 47 synagogues, they controlled everything, but in every major city the communists left a token religious community and one small synagogue,” Kaminetzky said in an interview with the Combined Jewish Philanthropies organization.

Joining the revival besides Pinchuk were Dnipropetrovsk business partners and future oligarchs Ihor Kolomoisky and Gennadiy Bogolyubov. The trio have donated tens of millions of dollars to Jewish projects in the city.

Kaminetzky was not just a spiritual leader. According to what Dnipropetrovsk businessman Edward Sartan told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in 2005, Kaminetzky also reconciled business disputes.

Feud with Kolomoisky

In 2013, Pinchuk sued archrival Ihor Kolomoisky and his partner Gennady Bogolyubov in London’s High Court for $2 billion, unleashing testimony on their sordid business dealings from 1999 until the mid-2000s.

Pinchuk claimed that they had wrongly held onto and profited from shares in KZhRK, a major Ukrainian ore mining enterprise, that he paid $143 million for in 2005.

Kolomoisky and Bogolyubov, however, insisted that Pinchuk’s claim over the shares derived from his sense of “entitlement” because he was the president’s son-in-law at the time.

Kolomoisky and Bogolyubov acquired KZhRK in July 2004 as part of the privatization of the Ukrrudprom Group, a state holding of ore mining businesses. Pinchuk insinuated in his claim that if it wasn’t for him, the pair would not have been successful in the state tender, as the law was designed to favor those who already owned shares in Ukrudprom – Kolomoisky and Bogolyubov included. Kuchma had the right to veto the law, Pinchuk pointed out. Kolomoisky and Bogolyubov agreed in their defense that Pinchuk used his influence to pass the law and to ensure an artificially low price.

The London court documents show that, while on a trip with Bogolyubov to Jerusalem in 2005, Kaminetzky received a phone call from Pinchuk. When Pinchuk heard Kaminetzky was with Bogolyubov, he asked the rabbi to relay a question about whether he would receive KZhRK if he paid $143 million for Alcross, a shell company that supposedly owned the shares of KZhRK.

Bogolyubov said yes, but when Pinchuk bought Alcross he found it owned no shares.

Nikopol Ferroalloys

Bogolyubov later claimed he thought that Pinchuk was referring to other money that he and Kolomoisky believed they were still owed for Nikopol – a ferroalloys plant privatized in 1999 and that they allege Pinchuk had promised, yet failed to share with them.

All three successfully bid for 4.6 percent of Nikopol in 1999, with Pinchuk owning half of the stake. They then agreed that any future shares acquired would be split equally, along with the profit. Between 2000 and 2003, Pinchuk’s Credit Dnepr bank and the Industrial and Financial Consortium of Pridneprovye acquired the majority share of Nikopol, but the defendants allege Pinchuk didn’t stick to the agreement.

Pinchuk also was accused by the defendants of abusing his connections to control state-owned enterprises and extract kickbacks. For instance, according to the defendants, in exchange for control over the board of Ukraine’s largest state oil and gas company, Ukrnafta, Kolomoisky (who owned 40.1 percent of the company) paid 50 percent of the profits into one of Pinchuk’s accounts monthly, plus $5 million a month into a “special fund” that Pinchuk allegedly said was for the upcoming 2004 election campaign.

Conversely, Pinchuk accused Kolomoisky of ordering the murders of three people, including a Dnipropetrovsk lawyer, and repeated corporate raiding. Kolomoisky has denied these accusations.

Neither side came off well from the pre-trial testimony.

Taken together, the depositions show how the oligarchy operated behind closed doors, colluding in privatization tenders to rob the state of revenues in auctions that should have been competitive.

The much-anticipated trial was settled days before the case was due to start in January.

Gongadze’s murder

On Nov. 28, 2000, crisis hit the families of Leonid Kuchma and Victor Pinchuk.

Two months after journalist Georgiy Gongadze went missing, the leader of the Socialist Party Oleksandr Moroz made a sensational speech in parliament.

He claimed to have recordings of Kuchma ordering Gongadze’s disappearance. On the tapes, a voice resembling Kuchma can be heard complaining about Gongadze’s articles to then-Interior Minister Yuriy Kravchenko:

“I say, as Volodya (Lytvyn, head of the Presidential Administration) says, the Chechens must kidnap him and take him to Chechnya by his dick and demand a ransom.” (Kuchma and Kravchenko, July 3, 2000)

“I’m telling you to drive him out, give him to the Chechens…Take him there, undress him, the fucker, leave him without his trousers, and let him sit there… He’s simply a fucker.” (Kuchma and Kravchenko, July 10, 2000)

In the weeks leading up to his kidnapping and death on Sept. 16, 2000, Gongadze voiced concerns to his friends and Ukraine’s General Prosecutor’s Office that he was being followed.

The recordings, which became known as the “cassette scandal,” consisted of more than 500 hours of conversations secretly recorded in the president’s office by Kuchma’s bodyguard, Mykola Melnychenko, from 1998 until a week after Gongadze’s disappearance. Aside from Gongadze, the tapes point to entrenched high-level corruption by the political elite – led by Kuchma.

Georgiy Gongadze, the journalist who founded Ukrainska Pravda, was murdered on Sept. 16, 2000.

Ukrainska Pravda journalist Pavel Sheremet (L) shakes hands with ex-President Leonid Kuchma (C) during the Yalta European Strategy annual meeting on Sept. 11, 2015, in Kyiv. On July 20, Sheremet was murdered by a car bomb in Kyiv, a reminder of the murder of Ukrainska Pravda founder Georgiy Gongadze on Sept. 16, 2000. Kuchma remains the top suspect in order Gongadze’s murder. He has always denied the accusation and has never formally been charged. (Volodymyr Petrov)

Gongadze’s beheaded body was discovered in woods in Kyiv Oblast on Nov. 2. In addition to the body initially being left in conditions that hastened decomposition, it also disappeared temporarily and turned up in a Kyiv city morgue. Several DNA tests later confirmed the body was that of Gongadze.

In 2001, the Labor Ukraine party that Pinchuk was affiliated with paid Kroll Associates, an American private investigations firm, to analyze the authenticity of the tapes. Kroll concluded that they had been doctored.

On the other hand, forensic audio specialists BEK TEK concluded that the recordings were authentic and had not been tampered with, and that the voices were indeed those of Kuchma and then-Interior Minister Yuriy Kravchenko. The owner of BEK TEK, Bruce Koening, who had been an FBI audio-verification expert, stated that their findings would stand up in a Western court.

No investigation within Ukraine has ever supported their authenticity. To some extent, the debate over the tapes was part of a diversion. With the prosecutor’s office controlled by the president, no serious investigation was ever undertaken by the Ukrainian authorities into the tapes, or the veracity of what was said on the tapes.

What’s a son-in-law for?

Pinchuk’s media outlets rallied to the defense of his father-in-law.

Fakty, Ukraine’s largest newspaper at the time, immediately produced dozens of disparate versions of Gongadze’s disappearance, amplifying the authorities’ contradictory statements. From claiming that he was still alive, and had been spotted by witnesses in various places in Ukraine and abroad (witnesses who later proved to be fake), to that he was killed by the same mafia types who falsified the recordings.

Kuchma and his supporters have long argued that the recordings were organized by his opponents and doctored to distort what had been said.

In 2002, the Financial Times correspondent to Ukraine Charles Clover, along with producer and filmmaker Peter Powell, was paid by an unknown source to produce an hour-long documentary entitled “PR.” It alleged that the U.S. government was using the Gongadze scandal to replace an innocent Kuchma with then-Prime Minister Viktor Yushchenko. In the two weeks leading up to the 2002 parliamentary elections, the film was broadcast three times, twice on Pinchuk’s ICTV and once on 1+1, whose programming was then allegedly controlled by Oleksandr Volkov, another Kuchma ally.

According to the 2003 book entitled “Beheaded” by Jaroslav Koshiw (Editor’s Note: The book’s author, former Kyiv Post editor Jaroslav Koshiw, is the father of Kyiv Post staff writer Isobel Koshiw, this article’s author): “The news on Kuchma’s son-in-law’s ICTV aggressively defended the president and attacked the authenticity of the recordings.”

The media campaign in support of Kuchma continued intermittently for over a decade after the killing, as the General Prosecutor’s Office opened and closed investigations into the murder. The investigation remains open today.

The highest-ranking person convicted in the murder of Gongadze was former police Gen. Oleksiy Pukach, sentenced on Jan. 29, 2013 to life imprisonment. Pukach has said Kuchma and Lytvyn should stand trial as well. Three lower-ranking police officers were also convicted and received lesser prison sentences.

After being driven from power with Yanukovych and other allies, former Deputy Prosecutor General Renat Kuzmin in 2015 told the Ihor Kolomoisky-owned 1+1 TV channel that Kuchma paid “a colossal $1 billion bribe to close the criminal case” against him. Kuchma called the allegations “yet another dirty lie” in comments to the Kyiv Post.

Without Kuchma

The Melnychenko scandal ignited an anti-Kuchma protest movement, “Ukraine Without Kuchma,” which became the basis of the 2004 Orange Revolution. Kuchma’s camp was accused of rigging the Nov. 21, 2004, presidential election in favor of his intended successor, Viktor Yanukovych. A public uprising forced a Supreme Court ruling and a re-run election, which Yushchenko won on Dec. 26, 2004.

Initially, the anti-oligarch rhetoric from the newly elected leaders, Yushchenko and Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, was strong. Tymoshenko went after a number of assets she said were unfairly privatized, including those of Pinchuk.

Kryvorizhstal reversal

She was successful in nationalizing and then re-privatizing the Kryvorizhstal steel mill, which was 44-percent owned by Pinchuk. Originally privatized for the rock-bottom price of $800 million in 2004, with his father-in-law still in power, Indian-owned Mittal Steel paid six times as much – $4.8 billion – only a year later in 2005.

Overall, however, attempts to right past wrongs waned, and the entrenched oligarchy created over the past 15 years fought back with vengeance and remained in power.

London court documents from 2013 show that Pinchuk acted together with other oligarchs to consolidate several metallurgy assets and protect them from the same fate as Kryvorizhstal: namely by creating an offshore company called Ferroalloys Holding. According to Kolomoisky’s defense referring to a meeting in 2006:

“The claimant said that he was concerned that if Yulia Tymoshenko returned as prime minister (she served from Jan. 24, 2005 to Sep. 8, 2005 and again from Dec. 18, 2007 to March 4, 2010), there was a real risk that the shareholding in Nikopol of 50 percent plus one share would be re-registered in the name of the State Property Fund of Ukraine.”

Despite their attempts, Pinchuk had to battle it out for control of Nikopol in the Kyiv courts, eventually winning on appeal in 2007. The review of past privatizations was discarded when Tymoshenko was unseated as prime minister in 2005.

Kuchma stays free

Justice for Gongadze took a similar turn for the benefit of the Kuchma family.

On the eve of Svyatoslav Piskun’s appointment as general prosecutor, a voice resembling his can be heard on a leaked recording, most likely released by a dissident security services agent, promising someone with a voice resembling that of Pinchuk that he will protect the Kuchma family in exchange for the appointment:

Piskun: Viten’ka (diminutive for Viktor), I beg you on my knees, and with every, you know what … go there and take this question in hand.

….

Pinchuk: In short, assure us, that you are a friend?

Piskun: Not only (a friend).

Pinchuk: A great friend.

Piskun: Yes. And tell him that we, as our families have been friends, we will continue to be friends. And everything will be fine.

(Alleged recording of Piskun and Pinchuk, Dec. 9, 2004)

In 2005, Piskun denied that such a conversation had taken place: “Of course, it was hoax,” he told Radio Svoboda journalists when asked about its authenticity.

At his Kyiv office in July, however, Piskun told the Kyiv Post he had reached out to Pinchuk to get Kuchma to reappoint him as prosecutor. When asked if the conversation took place, he gave a characteristically vague answer:

“I don’t remember. He (Pinchuk) said that the conversation occurred. I don’t remember it. Maybe it happened because I remember when the topic of my return was being discussed I talked to Pinchuk. I talked to Pinchuk. Why? Because for me Pinchuk seems more democratic. A more rightful person than Kuchma. Do you understand? So if I understood that Kuchma is the Red Commissar, Red Director. He has the soul of a communist. I considered Pinchuk a more Western person. But there was one phrase in that conversation: ‘I beg you on my knees.’ I never say things like that. I haven’t even knelt down in front of my own mother.”

Piskun: Tapes authentic

In his interview with the Kyiv Post, Piskun became the first senior official to admit to the authenticity of the Gongadze tapes and, moreover, that he believed, due to the FBI analysis carried out in 2003, that they were genuine even back then. However, he says there is not evidence that Kuchma ordered the journalist’s murder, as Kuchma did not use the word “kill.” Instead, he says a case needs to be opened to establish and investigate causal links.

Piskun: “I know what I know. I know what he said. And I believe that on those tapes there is the voice of Kuchma, (former President Viktor) Yanukovych, (then head of Presidential Administration Volodymyr) Lytvyn, Kravchenko and others. I know this. I believe the study that has already been done. But what is needed is to establish the causal link. This needs to be done by investigators.

Kyiv Post: But the causal link is that he was the president and he said these words to Kravchenko who was the head of Interior Ministry.

Piskun: Attention! They didn’t carry out the order. What was the order?

Kyiv Post: To take him to Chechnya.

Piskun: Why didn’t they take him to Chechnya?

Kyiv Post: I don’t know. I remember at that time there was a method that the security services used when they choked people. They did the same to Gongadze but for too long.

Piskun: And you’re telling me that? (laughs)

On March 4, 2005, the Gongadze investigation came to yet another halt after Interior Minister Yuriy Kravchenko was found dead in his home on the day he was scheduled to give evidence. The authorities declared it was a suicide, but some gun experts say it would have been nearly impossible for Kravchenko to shoot himself twice in the head.

Moving West

Even before his father-in-law left the presidency, Pinchuk began to expand his horizons.

In the summer of 2004, he held the first Yalta European Strategy summit in Crimea. There were around 30 attendees. Thomas Eymond-Laritaz, a foreign consultant and one of Pinchuk’s key advisers between 2004 and 2009, was one of them. At the time, according to Eymond-Laritaz, Pinchuk was looking for somebody to manage his international relations and non-business activities.

From 2006, with the help of Eymond-Laritaz, he started to fund large-scale philanthropic and development projects under the umbrella of the Victor Pinchuk Foundation. It has sent 80 students on part scholarships to study abroad since 2010; given scholarships to 2,000 students within Ukraine; created 32 neonatal centers across the country; provides training courses for medical staff dealing with war casualties, and supported the revival of the Ukrainian Jewish community.

It has sent 80 students on part scholarships to study abroad since 2010; given scholarships to 2,000 students within Ukraine; created 32 neonatal centers across the country; provides training courses for medical staff dealing with war casualties, and supported the revival of the Ukrainian Jewish community.

Pinchuk was the first Ukrainian oligarch to set up a foundation, and the others followed suit, Eymond-Laritaz told the Kyiv Post.

“There was a real philanthropic revolution in Ukraine that was driven by Pinchuk,” said Eymond-Laritaz.

Friends in high places

By 2007 and 2008, once he could demonstrate the success of the projects, Pinchuk was able to make connections with the international leaders he associates with today, according to Eymond-Laritaz.

His relationship with the Clintons is particularly famed. In 2015, the Wall Street Journal alleged that Pinchuk was the largest individual donor to the Clinton Foundation, giving at least $8.6 million between 2009 and 2013. The foundation in September also reported it has given an additional $7.4 million to the Clinton Global Initiative charity.

The clout that comes with such a friendship is evident. As an example of his access to White House, between September 2011 and November 2012, Pinchuk met State Department officials a total of 12 times, the New York Times reported.

Pinchuk has given nearly $1 million to Blair’s foundation and Blair has come to Ukraine several times at Pinchuk’s invitation. Last year, via Pinchuk, President Petro Poroshenko tried to bring Blair in as an adviser, although, in the end, it amounted to nothing more than a photo opportunity.

Pinchuk has been awarded a seat on the board of the Atlantic Council and the Brookings Institute, and was on the board of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, all prominent U.S. think tanks. He has reciprocated. In 2016, Peterson Institute and Brookings fellow Anders Aslund became a member of the board at Pinchuk’s Credit Dnipr, along with former International Monetary Fund head Dominique Strauss-Kahn.

Out of public office

The development of the foundation and the conference came hand-in-hand with Pinchuk’s moves to distance himself publicly from politics. When his second consecutive term as a parliamentary deputy ended in 2006, Pinchuk decided not to stand for office again.

Said Eymond-Laritaz: “The funny thing is that this transition – and he was the first one, the first large oligarch to decide to withdraw from politics at that time, I vividly remember – takes time to become reality. Today you can discuss politics and the name of Pinchuk never appears. So, in a way, this decision he took in 2004 and 2005 to withdraw from political life is a real fact now. It was a real fact before. But in a way he really stopped being an oligarch and became truly a business leader and philanthropist… 10 years ago, nobody would believe that a billionaire like Pinchuk could have nothing to do with politics, but today, it’s a fact.”

Around the same time Pinchuk also took the decision not to participate in any further privatizations in order to “cut the relationship between his business activities and the state,” said Eymond-Laritaz.

Star shows

Actor Kevin Spacey’s appearance at this year’s YES conference underscored Pinchuk’s transformation from son-in-law oligarch to international businessman. In heart-wrenching irony, Spacey walked onto the stage at the YES dinner at precisely the same moment the 16th anniversary of the Gongadze’s murder was happening across town. After giving an entertaining dinner speech, Spacey was ushered away by Pinchuk himself. A select number of guests were allowed to ask Spacey questions during a question and answer session led by Pinchuk. All of the questions focused on House of Cards, Spacey’s latest TV show.

In heart-wrenching irony, Spacey walked onto the stage at the YES dinner at precisely the same moment the 16th anniversary of the Gongadze’s murder was happening across town. After giving an entertaining dinner speech, Spacey was ushered away by Pinchuk himself. A select number of guests were allowed to ask Spacey questions during a question and answer session led by Pinchuk. All of the questions focused on House of Cards, Spacey’s latest TV show.

“Given the range of things you can do, and The Usual Suspects was a work of genius, how do you compare or prepare yourself from going from that to (Spacey’s character Frank) Underwood?” asked former U.S House of Representatives speaker Newt Gingrich from the audience.

No longer an oligarch?

Over the last decade, through his foundation and the conference, Pinchuk has presented himself to hordes of political and business leaders as a proponent of Ukraine’s European integration, and as a Western businessman.

This attempted image makeover comes despite the fact that his main business interest, Interpipe, is aligned with Russia or other former Soviet republics. The company has looked to break into new markets upon facing significant losses since Russia refused to extend its duty-free quotas in 2013, and global oil prices fell, shrinking the demand for railcar wheels and oil and gas pipes.

According to Dennis Sakva, energy sector analyst at Dragon Capital, Interpipe has $1.1 billion in debt. Political analyst Taras Berezovets sees no contradiction in Pinchuk’s openly European Union stance, while having hisbusiness in Russia.

Rather, he told the Kyiv Post, it’s a balancing act.

“He never was in favor of some sort of Soviet Union or whatever kind of union Putin would like to make with Ukraine,” said Berezovets. “He understands that Ukraine has much better prospects on the EU market.”

Silent on Putin

Ukraine’s political realities, however, have never allowed for full-fledged independence. Like almost all the Ukrainian oligarchs, Pinchuk is silent on Putin or Russia’s war to preserve his business in Russia, says Berezovets: “I don’t remember a single case where Pinchuk said anything about… Putin’s aggression.”

Similarly, when Yanukovych was elected president in 2010, he went after Kuchma for abandoning him during the 2004 Orange Revolution. Ukrainian prosecutors breathed new life into a criminal investigation into Kuchma’s suspected involvement in Gongadze’s murder. The case was closed because the Constitutional Court concluded the recordings were obtained illegally and thus “violated the person’s rights and their fundamental freedoms.”

Club with Yanukovych

The renewed investigation, however, didn’t stop Pinchuk or Kuchma from associating with Yanukovych.

This included membership of Yanukovych’s Kedr hunting club. The club and its membership, which included several oligarchs, was discovered by journalists in documents left behind by Yanukovych at his vast Mezhyhirya estate north of Kyiv when he fled Ukraine on Feb. 22, 2014.

Pinchuk told YanukovychLeaks journalists that his membership was not for resolving business problems: “The purpose of my stay at the hunting club was hunting.”

He said that he joined the club in 2008 when Yanukovych was in opposition. “When the situation changed, the rules dictated that one did not refuse an invitation from the president.”

Clinton’s friend

Pinchuk’s political capital, albeit in some dimensions limited, comes from his connections, as showcased at the YES conference, which brings together more big names than any other conference, as well as his ownership of three major Ukrainian TV channels. Together they have a combined viewership of 22 percent of the population, the Industrial Television Committee reported in September, meaning Pinchuk has the widest reach.

“He can sell these facts to the president or the Ukrainian government,” says Berezovets.

This has never been more true than in the post-Yanukovych era: the government’s promise of EU integration, its reliance on IMF money and its need for continued Russian sanctions has left it dependent on good relations with the West.

With Hillary Clinton likely to be the next president of the United States, Pinchuk may yet achieve what others in the Ukrainian elite can only dream of: being a personal “friend,” as Clinton called him at YES 2013, of the U.S. president.

Victor Pinchuk and ex-United Kingdom Prime Minister Tony Blair at the 12th annual Yalta European Strategy conference on Sept. 11, 2015 in Kyiv. (UNIAN) .

Escaping his past?

However, despite all of Pinchuk’s attempts to make people forget how he became wealthy, the past may haunt him forever. The investigation into Kuchma’s suspected involvement in Gongadze’s murder has never been closed. He clings to his TV stations. He tries to stay on the good side of whoever is in power. He spends at least as much on personal luxuries — like a $120 million London house — as his foundation gives away. And the largest recipients of his foundation have a self-promotional component: The Pinchuk Art Centre and the annual Yalta European Strategy conferences.

Oleg Rybachuk, the former chief of staff to President Viktor Yushchenko and one of Ukraine’s most prominent civil society leaders, casts doubt on Pinchuk’s sincerity. Just before the EuroMaidan Revolution, “when there was all this pressure from Russia and he had lots of business in Russia … he was very much in favor of Ukraine not moving towards the EU. His idea was it’s a mistake for Ukraine to become part of the EU. So he was looking for some compromise.”

His legacy, perhaps, is still yet to be decided.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter