The Russian Empire, which until its collapse in 1917 included Ukraine, was the last of the European powers to abolish slavery that had for several centuries existed in the form of peasant serfdom.

In the Ukrainian lands, Russian landlords had been free to sell, buy, exchange, exploit, punish, and even kill any kripak (Ukr. for serf). The great Ukrainian poet, painter and national prophet, Taras Shevchenko, himself a kripak for half his lifetime, didn’t live quite long enough to see the abolition of serfdom in 1861.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

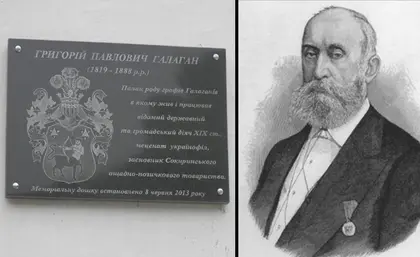

One of Shevchenko’s close friends, Hryhoriy Halahan, helped the Ukrainian peasantry to emerge as a class. Halahan significantly contributed to land reform which, by its scale and purport, could be compared to the Homestead Act in the U.S. He insisted that all peasants not only be freed from serfdom, but also be given plots of farmland in order to sustain themselves and feed the entire Russian Empire.

Halahan knew perfectly well that they would need money to cultivate their farmland, so he put in one million rubles to start a loan and savings society, the prototype of present-day land banks. That was a princely sum – one sixth of what the U.S. paid Russia for Alaska. Halahan maintained, “Ukrainian peasants should not borrow money from foreign banks or dishonest local moneylenders who despise the Ukrainian interest. They should have a reliable, legal lender.”

Halahan, the last but one male of a six-generation Cossack family, was born on August 15, 1819, in the village of Sokyryntsi, Chernihiv province. His father was a rich landlord who owned several villages and hundreds of hectares of land in Poltava and Chernihiv provinces. He received a very good home education. His tutor was Fyodor Chizhov, an associate professor of mathematics at St. Petersburg University and a multilingual connoisseur of world literature who translated into Russian “The History of European Literature of the 15th and 16th Centuries.”

Having graduated from the Law Department of St. Petersburg University, Halahan spent two years traveling across Western Europe. He then settled in his family estate in Sokyryntsi and decided to engage in agriculture.

In 1847 at age 28, Halahan was elected marshal of nobility of Borzna district, Chernihiv province. That same year, he married the daughter of a rich landowner. From April to October the couple lived in Sokyryntsi, and in the cold season in their large mansion in downtown Kyiv.

In 1850, Halahan became a school board trustee and a justice of the peace in Chernihiv. In 1858, he was appointed a member of the Chernihiv Province Committee on Peasant Affairs where he showed his commitment to the peasantry and organized relief aid to victims of crop failures. He actively and openly supported the abolition of serfdom and took an active part in drafting future peasant reform legislation. His consistent efforts to defend peasants’ rights often caused serious conflicts with local landlords.

Halahan’s biographers point to an interesting genealogical fact which weighed down on Halahan until his last days. It was about the treachery of his ancestor, Colonel Hnat Halahan, who commanded the Chyhyryn regiment of the Cossack army led by Hetman Ivan Mazepa. When the combined Swedish-Ukrainian troops were defeated by the Russian czar Peter the Great at Poltava in 1709 and Mazepa fled to Bessarabia, Hnat Halahan defected to the Russians.

Moreover, Hnat Halahan persuaded the Cossack leadership to surrender on allegedly safe and good terms: “Lay down your arms!” he told them. “All will be well: the Russian czar grants you freedom, authority, rights, and well-being. Just lay down your arms.”

Three hundred Cossack elders did so and were killed as one. Hnat Halahan was cursed by all Ukrainian Cossacks and generously rewarded by the Russian czar who gave him a lot more than 30 pieces of silver: the turncoat became the owner of vast areas of farmland near the town of Pryluky, Chernihiv province, and several thousand serfs to boot.

Hryhoriy Halahan knew the disgraceful story of his ancestor and must have felt an urge for redemption. It was his earnest wish to free Ukrainian peasants from serfdom. At the same time however, he never even thought of Ukraine being an independent state rather than a Russian province.

On his way back from St. Petersburg University, he wrote, “Why was I, a despicable being, born to do so much misery? Why am I condemned to be the unwitting culprit of the misery of so many people? And then, all my desire is to make as happy as possible the three thousand souls that have been bestowed upon me. I think about it more than anything else.”

One day, soon after he returned from his travels across Western Europe, Halahan attended a peasant wedding in a neighboring village where he saw a fiery folk dance and heard beautiful folk songs. As he recalled later, that dance and those songs brought him the true sense of the language, culture and spirit of his nation. It must have been then that the awareness of his national identity drew him to the field of Ukrainian folklore, ethnography and science.

He became the first head of the Southwestern Geographic Society and published a collection of Ukrainian songs and three volumes of works by Mykhailo Maxymovych, the man who founded and led almost all Ukrainian studies.

It was under Halahan’s leadership and with his financial and organizational support that Volodymyr Antonovych and Mykhailo Dragomanov founded the Ukrainian school of history.

And yet, holistically aware of his Ukrainian identity, he admitted that he was completely embedded in the Russian Empire.

In a letter to Mykhaylo Yuzefovych, the turncoat who was to blame for the arrest of most members of the Brotherhood of Cyril and Methodius, and whose hand clamped down the hardest on the Ukrainian language, Halahan wrote: “I confess that I will never, and in no way, be able to betray my deep love for my native tribe, but believe me, I feel no less Russian.”

Halahan financed Russophile publications in Lviv, thus contributing to the eradication of Ukrainian self-identity and to its cultural assimilation with Muscovy. In particular, je financed the first Russophile magazine in Halychyna (Galicia) called Slovo (Word). Its first issue came out in 1861, a few months after Taras Shevchenko died

The magazine promoted the idea of Halychyna and other parts of Ukraine – collectively termed as “Malorossiya” (Russia Minor) – being an organic part of the Russian Empire and the Ukrainians and Muscovites being one people

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter