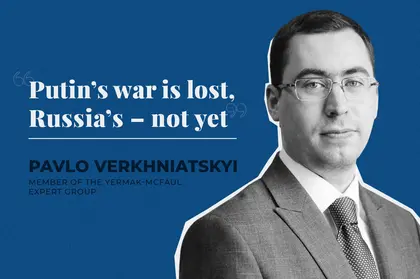

A graduate of the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, Pavlo Verkhniatskyi specializes in corporate intelligence and compliance. He is the founder of the Kyiv-based firm COSA, and member of the Yermak-McFaul Expert Group on Russian Sanctions.

Our conversation focused on economic matters mostly, but as it unraveled, we examined Russian society through the lens of two Ukrainians who know firsthand that in Russia actions do not always follow conventional patterns of logic.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

From riches to rags

When asked how Russian business felt in Ukraine after Russia’s first invasion in 2014 Verkhniatskyi answers, “Very comfortable, if not to say frivolously.”

Although it is trickier for Russians to enter the Ukrainian market, with enhanced due diligence checks, public scrutiny increased and state-owned banks like VTB and Sberbank sanctioned, big businesses, especially with decades-long embedded links, have managed to avoid repercussions.

He cites the real estate and energy business as an example. Despite elaborate, opaque ownership chains, some assets turned out to belong to Russian oligarchs now sanctioned by the West.

Similarly, the Alfa Group companies owned by businessman Mikhail Fridman and his partners, which include Alfa Bank, Kyivstar, Morshynska, and Borjomi – considered by some to be close to the Kremlin – have operated both during the Poroshenko and Zelensky presidencies, with Alfa Bank cards used for paying even governmental salaries.

Diane Francis Interviews Mikhail Zygar, Yaroslav Trofimov on Prospects of Russia’s War on Ukraine

After Feb. 24, the situation changed dramatically, Verkhniatskyi emphasized. Alfa Bank, for example, is on the verge of being nationalized even though there is a lobby attempting to prevent that.

Fridman, who until recently was a welcome guest in Ukraine, organizing jazz festivals and business forums, may now lose his business. Another Russian oligarch Vladimir Yevtushenkov, involved in the Russian military-industrial complex long before the full-scale war, has also had his assets confiscated.

Some businesses involving Russian nationals could not even repay their debts because their accounts are now frozen, and Ukrainian banks are instructed by the regulator not to process their transactions.

So, how did the situation effectively go from 0 to 100 percent after Feb. 24?

Good question, Verkhniatskyi notes, saying that vested interests coupled with lucrative schemes played a key role in the reluctance to introduce drastic measures earlier. He hopes that a sense of moral obligation contributed in part to the change, but it is also about reputation and political risks that now exceed monetary gains.

He adds frankly that the potential nationalization of certain companies related to Russians does not guarantee that these companies will not eventually return to their initial owners in the long run, by means of opaque methods of ownership.

Russia’s resources and undemanding poplulation

We proceed to talk about sanctions and their effectiveness in light of Russia’s continual attempts to circumvent them.

Sanctions are an effective and necessary method, Verkhniatskyi argues, but they require refinement. Before Feb. 24, they were nominal compared to what we see now, with many Western companies continuing to operate in the Russian market, tolerant in their approach to secondary sanctions and nearly no limitations regarding the banking system.

Although Russia has had limited access to technology, over 1,500 components from around 200 companies worldwide, including developed Western countries, have still been delivered, with some companies, for example, simply prolonging the existing pre-sanctions contracts, thus benefitting from a legal loophole.

Also, Verkhniatskyi says that since Russia is a big country with many resources it can cover some of its needs. Given that a large proportion of its society’s needs are basic, it helps the economy stay afloat.

After Feb. 24 the situation changed dramatically, with Russia now becoming the most sanctioned country in the world – and the sanctions do bite.

It still manages to circumvent some of them, as was the case with a cryptic company in Abu Dhabi with an email domain “mail.ru” that provides the kind of services well-known European companies had been doing in the Russian gas sector until recently.

The circumvention mechanisms are numerous and at times quite creative. So it is not easy to prevent it.

Nevertheless, the Yermak-McFaul Expert Group on Russian Sanctions, which recently co-authored the sanctions evasion paper, is already preparing to update it.

How other countries see it

Continuing the discussion, we touch on the grander geopolitical context of sanction evasion: namely, how non-Western, often authoritarian countries are helping Russia. And whether the West can impact them as their economies are intertwined.

“It’s a very good question. I have raised it several times on different levels, particularly what Ukraine is doing to impact those [non-Western] countries,” Verkhniatskyi says, adding that Kyiv mainly maintains a dialogue with Western countries, with much less attention to promoting its messages among the so-called Global South, where Russian reach, on the contrary, is very strong.

Overall, he admits that the situation is complicated, not least because the Russo-Ukraine war is a war of values, and not all European countries find an affinity with Asian and African autocracies, where some regard Putin and his regime as a bulwark, or are simply happy to accept his money.

“Josep Borrell, [EU’s top diplomat] noted this in his latest momentous speech,” Verkhniatskyi emphasizes, saying that states like Vietnam, India, Brazil and China are also helping Russia, including in international organizations, or simply within trade deals others would be squeamish about.

Yet for all the support that Russia may seem to be feeling from that part of the world, the countries in question are also pragmatic, and that is something that Ukraine and its partners may be willing to exploit through diplomatic channels and other means.

“For example, the idea of an oil price cap, designed to decrease Russian oil revenues looks like a good initiative,” Verkhniatskyi says.

He adds that many countries – including those of the Collective Security Treaty Organization and marginals like Serbia – are now trying to distance themselves from Russia, with Kyrgyzstan recently refusing to host the drills dubbed “Ironclad Fraternity.”

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi likewise pushed back on Putin during the Shanghai Cooperation Organization leaders’ summit in Samarkand, Uzbekistan.

“Some Indian companies are reaching out to me to ask how they are perceived in Ukraine and whether they’ll be able to rebuild it, and I answer that in my opinion, until India joins the sanctions, there will be no significant additional opportunities for Indian businesses here. Americans and Europeans are helping us, and thus they will be the ones benefitting here after the war,” says Verkhniatskyi.

The Russian army isn’t bad, it’s just the Ukrainian one is better

We proceed to talk about the battlefield. Verkhniatskyi addresses the subpar performance of the Russian army, saying that it stems from when the current Minister of Defense Sergey Shoigu took office in 2012. His predecessor Anatoly Serdyukov and his accomplice Yevgeniya Vasilyeva were implicated in a $100 million embezzlement case that cost them their jobs.

“In 2013, as a young analyst, I wrote a paper presented to certain European embassies and multinationals about Shoigu and the measures he took after Serdyukov. It did seem like he managed to fix the surface, but as it turned out, they in no way stopped stealing,” he says.

So, when in 2014 the so-called “green men” arrived in Crimea well-dressed with modern arms and equipment, Verkhniatskyi had the impression that there was something odd about this: “I believe they sent their elite troops, attempting to create an illusion that this is what the entire Russian army looks like.”

This impression was fueled by Russia’s constant plans “in the making,” such as the creation of the Armata tank, which to date remains little more than a prototype.

“The Ukrainian army and territorial defenses have done unreal things. At the beginning of the war, they were truly stressed as the Russians had a lot of equipment. But later they understood that the so-called empire no longer had full capacity, not least because of the restrictions on the foreign military supplies since 2014 and the internal multilevel corruption,” he says. “It’s not that the Russians were weak in all respects, it’s just the Ukrainians were undervalued.”

Putin’s war is lost, Russia’s – not yet

In another time-traveling exercise, we go back to the late 2000s when Putin’s regime was at its peak. It is precisely at this time that Verkhniatskyi studied at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, offering a peek into what the sentiment was like among the students and the professors.

Except for the international relations faculty, most of the university was not overly politicized, he notes.

“For example, we’d take a piece of paper with a NATO logotype to list the present students, and pass it to the professor,” Verkhniatskyi says. He describes the Dugin-inspired Eurasianism optional seminars in the late 2000s at his alma-mater, Moscow State Institute of International Relations, which he and other student attended out of curiosity.

“Our economics professors could openly say that the data provided by the Russian authorities is unworthy, or that it is a lie that Russia is about to detach from its dependency on oil and gas revenues,” he says, adding, however, that one of the most overt propagandist speeches he heard there was delivered by the Russian Federation Senator Aleksey Pushkov, a household name at one time, whose influence in Russian has become less conspicuous over the years.

“He simply walked in and said that Ukrainians don’t have a history and that Poland has twisted its own too,” he recalls. “Overall, Russians like to label foreigners using slurs, having a special one for most nations.”

We view that notion through a lens unfamiliar to the Western mindset: how in Russian culture such labeling is not necessarily an offense, it’s the norm. Whether on the level of interracial or domestic relations, or daily interaction, the notion of respect is lower in that part of the world.

Perennially dissatisfied and angry, Russian society is accustomed to conflicts, erratic behavior, and grand speculations, as often depicted in Dostoevsky’s novels.

It is also subservient, according to Verkhniatskyi, who believes that contemporary Russian bureaucrats, policy makers and other officials share three main qualities: love for easy money, servility, and fear. Putin nourished them throughout the years, deterring them from opposing the regime.

But now that his war has been lost from a political perspective, the Russians will seek an alternative.

The regime will fall, and figures like Nikolai Patrushev will not necessarily take over in replication of the Brezhnev-Andropov succession style, Verkhniatskyi contends, betting instead on the opposition and even the potential collapse of Russia. He also assumes that the mysterious deaths of top executives in Russian corporations recently could be explained by their attempts to find Putin’s “successor.”

“We should not exclude scenarios where the people from the system remain in power, bringing up someone comfortable to all sides as a front man. This, however, still might not keep Russia with its current borders,” he adds. “A scenario where Putin keeps the throne for a while is very unlikely, but possible, which could take place only if he stops the war, pulls back and presents this to his people as a victory.”

Vilifying Ukraine

Elaborating on the complexity of Russian society’s modus operandi, we touch upon why Russians are not acting the way certain Western politicians and commentators expect them to, including when it comes to challenging Putin’s regime more systematically.

“You’re absolutely right when you say that they vilify Ukraine much more than they do their own government for all the problems and the inconveniences they experience as a result of the war. This applies to the mobilization too. Just because they crossed over the border with Georgia to save their lives doesn’t mean that many of them stopped being chauvinists,” says Verkhniatskyi.

He contends that even though the Russians are “marinated” in propaganda daily, it is true that the support for the war is shared by some educated individuals who travel abroad and until recently visited Ukraine as well.

“I keep in touch with some acquaintances in Russia and the emerging consensus is that even though the war is bad, Russia should proceed and achieve better bargaining power, which actually means killing more people and causing more destruction. How wicked is that?” he asks rhetorically.

“We lived as though Russia weren’t deranged”

As our dialogue slowly wraps up, we talk about the war and its outcome.

Verkhniatskyi is confident that Ukraine can liberate the territories occupied by Russia post-Feb. 24, especially with new weapons flowing in.

He still believes that NATO should have closed the Ukrainian sky early on, with a no-fly zone, by resorting to the same audacity as the Russians do when saying that they are merely carrying out “a special military operation.”

“And we’re simply closing the sky. Just don’t fly around here,” he says, adding that Russia’s behavior is oftentimes much less fierce than it likes to portray. When Turkey shot down a Russian bomber in 2015 over its territory, Moscow was churning out threats in its typical manner, but in the end, it just banned the import of certain fruit.

While Russia is possibly experiencing a shortage of some ammunition and is using Belarus as a way to keep the Ukrainian troops pinned in the north, he warns against fully underestimating the enemy. In terms of arms supply, Ukraine still needs more equipment for the infantry to be transported safely, as well as tanks, air defense systems, artillery and ammo.

It also needs warplanes, which he is positive Ukraine will get, hopefully sooner rather than later, as it takes time to approve and implement decisions.

“The return of Crimea may happen, but it will probably occur simultaneously with the demise of Putin’s regime, which would involve a deal with the new government,” he speculates, adding that the use of nuclear weapons most likely terrifies even Putin’s loyalist. “They [Western intelligence], I believe, have ears most likely in the Russian government, which is why the situation is somewhat monitored.”

Talking about the European armies, Verkhniatskyi says that the war exposed some of them being worse off than expected, including that of the Bundeswehr.

Poland, however, takes the threat seriously, buying tanks and other modern systems from Korea and the U.S., while producing some of its own. It is on its way to becoming the strongest army in Europe. Cooperation with the U.S. defense industry makes this process even quicker and consistent: something to consider during the rebuilding process in Ukraine.

In an ideal world, he argues, all this money would instead be spent on other needs, but “when you have a deranged neighbor, you can’t afford that,” he says, then adds: “All these years, we’ve lived as though Russia weren’t deranged. Look where it got us.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter