Editor’s Note: This story has been expanded to add more commentary from experts.

One month ago, Ukraine launched its new wholesale energy market, with mixed results.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

The change, two years in the making, completely reworked how electricity is sold. Before July 1, the state enterprise Energorynok bought energy from all producers and sold it to regional and independent distributors at fixed rates.

- Check out the freshest Ukraine news items as of today.

- Check out the freshest Ukraine news items as of today.

Now, consumers, especially businesses, can choose how they buy their power in one of four market segments. From least to most expensive, these are as follows: bilateral deals with energy suppliers; a market to buy power for the following day; a market to buy power for the same day; as a last resort, consumers can buy power on the so-called balancing market, mere minutes before they need it.

The system worked. There were no blackouts. But some problems showed up in the first two weeks. Industrial energy costs spiked by up to 30 percent. Heavy restrictions on some producers hamstrung competition. Regulatory gaps remained unfilled. Lawsuits threatened to paralyze parts of the energy infrastructure.

“We are in a transitional stage,” said Svitlana Teush, an energy lawyer at Redcliffe Partners. “The new market model is not yet fully functional, with substantial administrative interference.”

She also said that there is currently insufficient competition and market liquidity, among other challenges. The European Delegation echoed her words in an emailed statement.

“We welcome the reform step made but think that much further work is needed to complete the opening of the electricity market to the benefit of citizens and business in Ukraine,” the delegation wrote.

A new system

The new energy market law, adopted in 2017, was supposed to bring in real competition and bring Ukraine closer to integration with Europe. The European Union even made energy market reform a prerequisite for receiving its next 500 million euro assistance tranche.

The reform rolled out in two parts. The retail energy market launched in January, while the more significant wholesale market was scheduled for July 1.

As July neared, some of the same international bodies that pushed for the change, began to suggest that Ukraine consider pushing back the launch date by at least a few months. For example, the World Bank warned that parts of the regulatory base and the needed IT systems would not be ready and a premature launch would threaten the new market. The European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development agreed, remaining supportive but suggesting a smoother transition.

Some Ukrainian officials agreed, including President Volodymyr Zelensky and members of his team. Zelensky even introduced a law trying to push back the start date.

Others, including Energy and Coal Industry Minister Ihor Nasalyk pushed back, insisting that the launch happens on schedule.

Attempts to delay did not work. The new system, warts and all, kicked in on July 1.

On July 16, lawmakers, regulators, state enterprises, power suppliers, industry representatives, energy investors and other stakeholders met in parliament to discuss the new market’s status. Many agreed — now that the market has launched, there is no going back.

But the main problem — the increased cost of electricity — drew complaints and outrage.

Growing costs

According to Ukrenergo, the state enterprise that operates the country’s backbone grid, energy costs for industrial consumers increased between 14 and 28 percent since the start of July.

The Cabinet of Ministers earlier in July released a statement criticizing Ukrenergo’s methodology for calculating the price increase.

However, the Federation of Employers of Ukraine, a major business association bridging companies in metallurgy, produce, chemicals, engineering, communication and other sectors, had similar findings to Ukrenergo. In the first week of the new market, energy costs for the federation’s members increased by about 25 percent, according to public statements.

“The prices of all the energy producers went up,” said Andriy Gerus, Zelensky’s representative in the Cabinet of Ministers and an energy expert.

“On monopolized markets, prices usually jump up when liberalization is done. It’s right to do liberalization on competitive markets,” he said.

According to Gerus, the average price for (state nuclear energy producer) Energoatom grew by 25 percent in July, compared with June. The average price of thermal (coal) power plants grew by 20 percent. The average tariff of (state hydroelectric producer) Ukrhydroenergo grew by 40 percent.

Multiple energy experts who spoke to the Kyiv Post agreed that energy costs went up across the board. However, some experts cautioned that the actual percentage would be hard to figure out until data for the entire month of July becomes available in August.

Soaring tariffs

Before July 1, Ukrenergo had a transmission tariff of 5.7 kopecks per kilowatt-hour. The National Energy and Utilities Regulatory Commission decided that starting July 1, this tariff would become 34.7 kopecks per kilowatt-hour. Another routing tariff of 8.9 kopecks per kilowatt-hour was added on top of it.

To energy customers, the change was a stunning sixfold increase. An Ukrenergo spokesowman said that the grid operator merely inherited this tariff from Energorynok, whose responsibility it was before the new market launch.

Another thing that Ukrenergo inherited from Energorynok is responsibility for the green feed-in tariffs paid out to renewable power plants. The government enterprise, Guaranteed Buyer, must pay the feed-in tariff to renewable producers but the money comes from Ukrenergo.

Renewables are a small but growing portion of the energy market and their prices are disproportionately high. This year saw a massive surge of new renewable projects trying to grab the last of Ukraine’s generous feed-in tariff before the end of the year.

Energy expert Andrey Buzarov said that Ukraine has an “unrealistic” energy balance for 2019, which overestimates the share of energy production from renewables.

“It is necessary to adjust the energy balance, reducing the share of renewable energy sources to realistic values,” he said.

Steel vs. green power

The sharp increase in the tariff raised many eyebrows but the strongest response came from ferroalloy producers, for whom electricity can be between one third and two-thirds of the cost of production, according to statements made by several metallurgy plant representatives in parliament on July 16.

“We will not survive working at a loss,” said Volodymyr Kutsyn, the head of Nikopol Ferroalloy Plant, who said that a 25 percent increase in power costs meant millions in losses per month. Other metallurgy industry representatives backed him up. Metalworkers protested outside NEURC offices.

The Nikopol plant, which belongs to oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, along with four other metallurgical companies filed a lawsuit in the Kyiv Administrative District Court, to block these tariff regulations. The court granted an injunction against the tariffs in late June. This prevented Ukrenergo from collecting the full amount it needed to cover its expenses.

Late in the afternoon on August 1, the court lifted the injunction and unblocked the tariffs, according to a statement by Ukrenergo. Only the five plaintiff companies are currently exempt from having to pay the full amount to Ukrenergo.

The lawsuits had raised concern among renewable energy developers and investors. The industry group European-Ukrainian Energy Agency, which comprises multiple Ukrainian and international green energy companies sent a letter to President Zelensky, writing that as a result, Ukrenergo was not able to compensate the Guaranteed Buyer, which threatens to destabilize the renewable energy market.

“The implementation of financing agreements with national and international credit institutions… is being finalized now for several renewable projects representing 500+ MW and worth several hundred million euros of investment,” European-Ukrainian Energy Agency wrote.

Experts had warned that the case may have hurt the new energy market and Ukraine’s reputation among international investors, the longer the standoff continued. Buzarov said that international energy investors would be willing to turn to international courts to protect their investments — and they would win.

“In order to ease the growing tension amongst market participants and mitigate the impact on industrial consumers following the transmission tariff increase… it may be necessary to begin developing solutions now,” said Teush.

Nuclear, hydro hamstrung

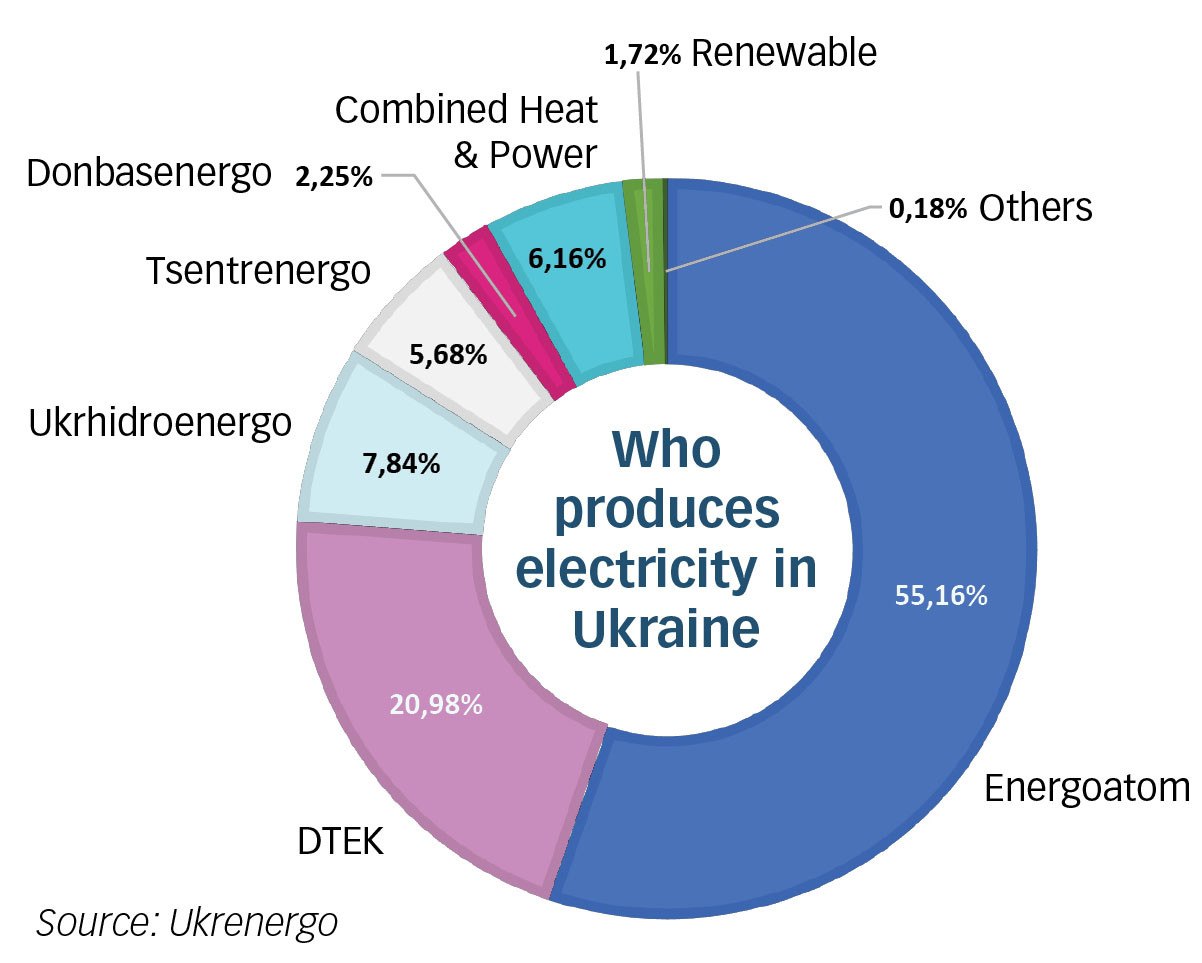

Government power companies, which create most of Ukraine’s electricity have to work under heavy restrictions, limiting their role in the market.

“The [market] fragmentation reduces market liquidity,” wrote the European Delegation. “Furthermore, as market players are obliged to sell certain amount of their production in the tightly or semi regulated markets, the other players may gain market power in the remaining wholesale market segments.”

Energoatom, which encompasses all of Ukraine’s nuclear power plants, produces about 55 percent of Ukraine’s total energy. But its total share of the energy cost is only 26.6 percent, according to Ukrenergo.

A Cabinet of Ministers decision in June forced Energoatom to sell 75 percent of its energy at a fixed rate to the state’s “guaranteed buyer,” for the sake of the population. Energoatom also has to allocate 15 percent more to balancing out the grid.

Only 10 percent of all nuclear power is available for purchase in the competitive market segments. This denies many companies the opportunity to make a bilateral deal with Energoatom and buy cheap nuclear power.

All this means that industries have to turn to the more expensive market segments and the pricier coal-fired thermal electricity. Thermal plants make about 30 percent of Ukraine’s electricity but account for 47 percent of all energy costs in the country.

Energoatom President Yuriy Nedashkovsky said on July 16 that “Energoatom’s right to equality was violated” and that during the first two weeks of July, no energy was sold outside the obligatory amount. According to Nedashkovsky, industrial consumers could have had access to 30 percent cheaper energy.

However, Yaroslav Mudriy, the managing partner of energy company ERU Trading, said that even though only 10 percent of Energoatom’s electricity saw a price increase, it was enough to push prices higher in the energy marketplace.

According to Ukrenergo, thermal plants are trying to sell as much electricity as possible in the most expensive segment of the market — the balancing market. The reason is that nighttime price caps on the day ahead and intraday markets are too low.

“Therefore, thermal power plants are not interested in selling electricity in these segments, especially at night and are trying to maximize in the balancing market, which is much more expensive,” Ukrenergo wrote.

Setting aside a huge percent of nuclear power is supposed to guarantee low prices for the population. However, Viktoria Voitsitska, an outgoing lawmaker and Secretary of the Parliamentary Committee on Fuel and Energy complex, suspects that more is at play.

“Someone is taking cheap electricity from Energoatom and is adding their margin on top of that and is selling it to end consumers,” she said. “Both the private companies and the public sector.”

Voitsitska said that if industry and municipal services see a consistent increase in energy costs, they will pass those costs along to Ukrainian households. All products and services that depend on electricity — which is all of them — will become more expensive, hurting Ukrainians whose paychecks will not climb to compensate.

Multiple stakeholders suggested that one way forward would be to reduce the size of Energoatom’s public service obligations or impose a public service obligation on private thermal power plants.

According to Gerus, Voitsytska, and multiple other commentators, the current state of the market greatly benefits the coal and energy giant DTEK, owned by Ukraine’s wealthiest oligarch, Rinat Akhmetov. DTEK generated about 20 percent of the country’s electricity.

DTEK spokesman Maksim Asaulyak responded that the new system did not significantly change DTEK’s share of the market and that the company believes that more nuclear energy should be traded on the direct contract market.

According to earlier statements, DTEK has 24 percent of the bilateral market and 12 percent of the day ahead market. DTEK is active in all segments, according to Asaulyak.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter