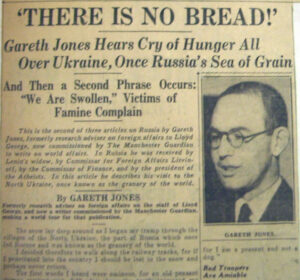

The great nephew of Gareth Jones, the Welsh investigative journalist, known throughout the world for being one of the few in his day to report on the 1932-33 man-made famine in Ukraine, the Holodomor, says Russian leader Vladimir Putin is using economic warfare against Ukraine by “weaponising food, which is shocking and disturbing”.

Speaking in an interview with the Kyiv Post, Philip Colley said that with wheat and other grain still blockaded in Ukrainian ports by Russian naval vessels, the casualties of this war could spread far wider than its borders, with famine being one of its consequences.

- View the most up-to-date Ukraine news articles published today.

- Obtain the most current Ukraine news articles released today.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres, speaking last month in New York, said this about Russia’s war in Ukraine: “It threatens to tip tens of millions of people over the edge into food insecurity, followed by malnutrition, mass hunger and famine, in a crisis that could last for years. Between them, Ukraine and Russia produce almost a third of the world’s wheat and barley and half of its sunflower oil.”

“It’s absolutely horrifying, what is happening in Ukraine,” said Colley.

“In the early stages of the war I had an image of Gareth, my grandmother’s brother, walking through the streets of Kharkiv and then seeing those missiles come in and destroy the buildings in the square.

“This, followed by images of people queuing for food, the exporting of grain being stopped, and the stealing of grain. History is repeating itself.”

Colley, 57, said that if Gareth Jones were in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second largest city today, his newspaper articles would be plastered on the front pages of most national newspapers, though back then they were suppressed.

“The Soviets wanted to suppress stories, the friendly Western journalists living in Moscow helped them do that, and the British government suppressed the news of the famine, which probably indirectly led to Gareth’s death.”

Colley is convinced that had they been honest and not held back the news of the famine to please the Soviets, Gareth would have been exonerated and believed.

(Photo Credit: George Carey, from documentary “Hitler, Stalin and Mr Jones” directed by George Carey)

“But their inability to back him up made journalists like Walter Duranty, a New York Times correspondent, and Pulitzer Prize winner, who supposedly reported on events in the Soviet Union objectively, let them get away with it.”

Despite being castigated and ridiculed for his articles, Gareth continued his good work. In The Times (London), dated October 14, 1931, Jones wrote:

“In the Ukraine, in one collective the ration was 20 lb. ‘The peasants complain: Come and see the grain, rotten grain: that is what they keep for us. All the best grain is sent to the nearest town for export, and we do not get enough to eat. Poor Mother Russia is in a sorry plight. What we want is land and our own cows.’ In some villages the government seizure of grain has lead to fighting between the peasants and the Communist authorities.”

Gareth was also head-hunted by Dr Ivy Lee, a leading American public relations expert, to find out what was going on in Russia and Ukraine in 1931. He was accompanied by a young Jack Heinz – heir to the food manufacturing empire – where they witnessed the onset of starvation in the country.

He then writes a letter to Mr Ivy Lee on September 15, 1932, saying: “The harvest is a failure and there will probably be starvation for millions this winter. There is at the present moment a famine in the Ukraine.

“The collective farms have been a complete failure; and there is now a migration away from the farms. There is simply nothing left in many of the collectives and numbers of peasants from as far South as the Bessarabian frontier have wandered up to Moscow to search for bread. Even the army is short of food and there is grave discontent in it.

“Disillusion is spreading rapidly through the ranks of the party. There is now no open opposition, but the silence is dangerous.”

Philip’s interest in his great uncle began as a child. “I heard this exciting story about him being captured by bandits in China. Later in life I wrote a thesis called ‘The Life and Murder of Gareth Jones’.

“Back then we didn’t know so much about the famine, our interest was how he was killed. It wasn’t until later on that we found out about the reporting in Ukraine and the Soviet Union.

“We didn’t link it to the murder in Inner Mongolia in August, 1935, nor did the Foreign Office, when they did their investigation. All the records allowed back then were all geared to a German-Japanese pact.”

Colley is convinced that more research is needed on his great uncle and that there are documents yet to be released by the British government on his activities and the Ukrainian Holodomor.

These days historical events are projected onto film and in 2019 Mr Jones hit the cinematic screens. Colley’s views on the film are mixed. “I am a stickler for historical accuracy. The film did a great job of getting over the story of the Holodomor, but it did not reflect the true story of Gareth.”

Colley highlights these concerns on the Gareth Jones website in some detail, such as the fact that Gareth never met George Orwell, nor did great uncle have a love interest as portrayed in the film, and that there was famine in other parts of the Soviet Union.

He admits though that there had to be some creativity for Hollywood, but argues that the true story of Gareth Jones can best be found in the book ‘More than a Grain of Truth’ by Dr Margaret Siriol Colley, his late mother.

Colley has been to Ukraine. He went with his mother in 2010 to attend a Chekhov Conference in Kyiv.

Years later he’d heard that there was a street named after Gareth in Kyiv’s Shevchenkivsky District, so a future trip could be in the offering. “I’d love to walk down that street and see his name there,” he said.

There is also a historical plaque at The University of Wales, Aberystwyth, in honour of Gareth, which is undergoing renovation.

Colley believes more research needs to be done on the life of his great uncle. Anybody with more information is more than welcome to make contact with their website at garethjones.org

In the meantime, Ukraine has to deal with the consequences of Russia’s invasion. It is Russian bombs and mines, strewn across its steppes, that have been preventing farmers from planting and harvesting. It is estimated that around 20 million tons of wheat are trapped in silos near Odesa and in ships filled with grain that are stuck because of the Russian blockade.

Ukraine will have to deal with this situation so that the deadly hunger witnessed first hand by Gareth Jones does not appear once again on the territory of this fertile land.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter