When their apartment block in northern Kyiv goes dark just after 6:00 pm as scheduled, residents Iren Rozdobudko and Igor Zhuk are ready.

She lights a candle, he switches on his head torch, and they settle in for a quiet evening.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

For much of the past month, Russian strikes have heavily targeted Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, severely damaging the electricity network.

To ease the strain on the grid and avoid a total blackout, national energy operator Ukrenergo has imposed controlled power cuts in the capital and elsewhere across the war-torn country.

Residents can consult the official schedule for rolling blackouts to pinpoint exactly when their lights will go out.

The buildings in the neighbourhood where Rozdobudko and her husband Zhuk live experienced three four-hour power cuts on Saturday — from midnight to 4:00 am, 9:00 am to 1:00 pm and again from 6:00 pm to 10:00 pm.

“I like the semi-darkness, when it’s quiet, moody and no one interrupts my thoughts,” says Rozdobudko, a 60-year-old writer and artist, as she prepares a vegetable salad.

‘Agony and powerlessness’

If she had to, Rozdobudko says she could cook borscht, a traditional beetroot soup, “with my eyes closed”.

The gas stove in the flat still works and water comes out of the tap even if the pressure is weak, she says.

“There is cabbage in the fridge, carrots and other necessary items,” she adds.

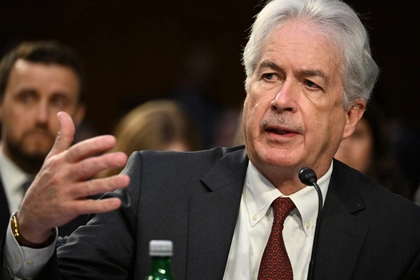

Zelensky Meets CIA Director William Burns in Ukraine

With winter fast approaching, the writer is grateful that the heating still works too.

Flashlights as well as candles, bought long ago for decorative purposes, keep their flat illuminated.

In the bathroom, they have put up a camping lantern.

Outside, the neighbourhood is plunged into darkness, the odd faint light emerging from the windows of some nearby apartments.

The pitch-black pavements are lit up here and there by residents using torches or mobile phone lights to guide them home.

But so widespread is the damage to Ukraine’s electricity infrastructure that Ukrenergo said at the weekend the controlled blackouts were not enough to relieve the grid and additional power cuts had to be imposed.

On Sunday, even the streets near the presidential office in Kyiv, which had so far escaped the power outages, briefly went dark, AFP reporters saw.

Parts of the capital also experienced interruptions to water supplies last week, following renewed Russian missile attacks.

Sitting by candlelight, Rozdobudko passes the time sewing doll’s clothes. “I’d never be doing this if the lights were on,” she admits.

The recent salvo of Russian strikes on the capital, after a months-long lull, is a stark reminder of the war raging on the frontlines in eastern and southern Ukraine, where deadly bombardments are a daily occurrence.

For Zhuk, a scientist and singer, the bombing of civilian infrastructure shows “the agony and powerlessness of the Russian army”. Moscow’s troops are struggling to resist a Ukrainian counter-offensive that saw Kyiv’s forces retake thousands of square kilometres in the northeast in September.

Bracing for winter

“When they see that they can’t defeat the (Ukrainian) army, they start fighting with those at the back — the civilians,” he says.

In the heart of Kyiv, the city’s iconic Independence Square, known as the Maidan, regularly goes dark.

Without the streetlights on, only the headlights from passing cars cut through the blackness after nightfall. Restaurants have adapted too, offering candlelit dinners.

Almost 4.5 million Ukrainians were temporarily without electricity nationwide on Thursday night, President Volodymyr Zelensky said, accusing Russia of “energy terror”.

Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko has warned of a “worst-case” scenario this winter with “no electricity, water or heating” if Russia kept up its attacks.

He said the city was preparing more than a thousand heating points where residents could keep warm as the weather turns ever colder.

“We have bought electric generators, stored water and everything necessary for these heating points to accommodate people,” he said.

Zhuk, the torchlight on his forehead burning brightly, says he has resigned himself to a challenging time ahead.

“It will probably be a bit more difficult this winter, or maybe even a lot more difficult. But we’re not in the worst situation yet.”

In a corner of the flat, Rozdobudko visibly moved, points to a letter on display. It was written by her grandchildren, who have found refuge in the French city of Marseille.

“Hello grandpa and grandma. Is life going well in Ukraine?” the letter reads.

“If not, come and join us in France. We love you very much and we support you.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter