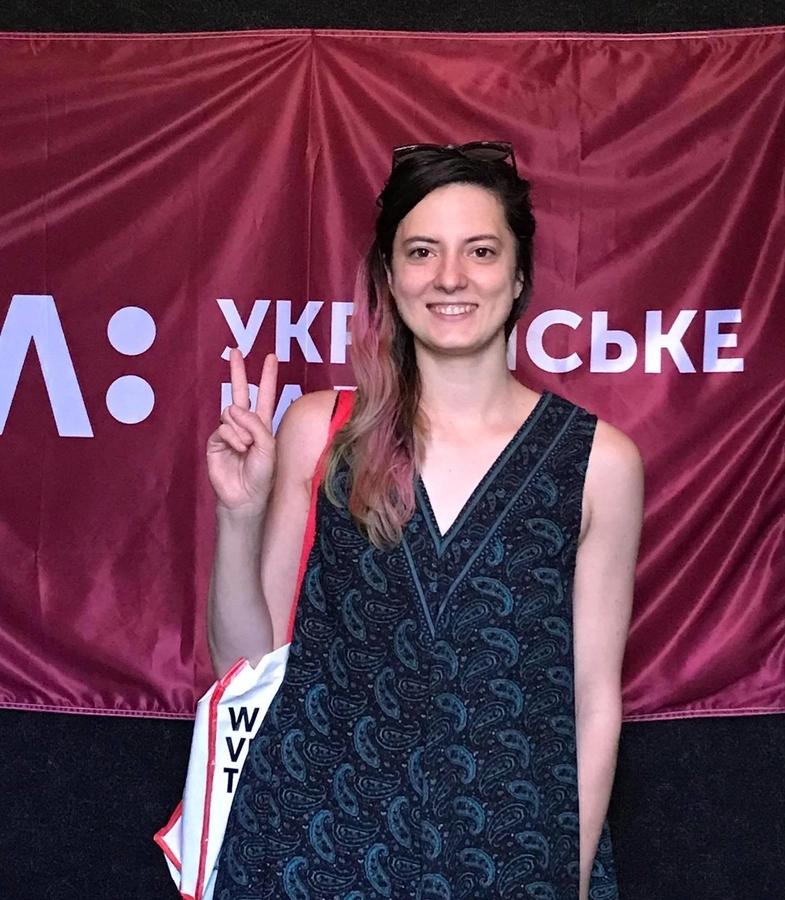

Iana Boitsova is one of the founders, together with Fedir Boitsov and Ali Kadoum, of Pixelated Realities, which recently drew acclaim for the war documentary project of the Museum of Ukrainian Victory (MOUV). The company’s mission is to improve the methods of cultural heritage preservation. Its team was based in Odesa, but is now dispersed in different countries.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Iana Boitsova

It is rather unusual to see IT specialists dealing with culture instead of e-commerce. How did you and your partners meet and decide to start up Pixelated Realities?

Our story began when our founders Fedir Boitsov and Dmytro Dokunov became fond of a type of 3D scanning with a photo camera – photogrammetry, which is now our specialty. In winter of 2015 they 3D-scanned the statue of Duke de Richelieu in Odesa, because they were afraid it might be lost or damaged due to a Russian aggression and possible war. Later, in 2016, after analysis of the start-up market, we understood that it is more plausible to have an impact in heritage digitization with an NGO. As a new business, this market was non-existent even in the EU. So, the three of us founded Pixelated Realities in Odesa, with me as a manager of digital and educational projects, Fedir as an architect, 3D modelling and printing specialist, and Dmytro an experienced operator and drone pilot. Soon enough Ali joined the group as a fellow architect for modelling. In 2021, Dokunov left us, and after the Russian attack he joined Ukrainian Armed Forces.

Russia Strikes Odesa and Kharkiv City Centers with Missiles, Casualties Reported

What is photogrammetry?

Photogrammetry is a method of visually surveying a real-life object, which helps to obtain data abouts its surface, form, color, and in some cases roughness, luminosity, etc. We use very common digital photography as an instrument, and take hundreds, or in the case of buildings, thousands of photos of the object from various angles. With specialized software, like Epic’s Reality Capture, it allows us to get a point cloud and then a 3D model by understanding the position of a single color spot in the space between two camera shots. The program builds a triangle between the two camera shots and a color point by knowing the focus length and camera parameters.

The interesting thing about photogrammetry is its precision, its possibility to capture photorealistic (obviously) color and its quickness compared to traditional measurements and survey techniques. The number of technology implications is rather wide, from online visualization for 3D viewers, games, movie productions, AR, VR and projection mapping, to collecting data for architectural projects, production of copies with 3D printing and milling, prototyping, art and science projects etc.

Every person on our team is at first a photographer, sculptor, artist or architect; then all of us learn to become a 3D artist and photogrammetry specialist. You can’t just go and hire this kind of talent. It is like training a doctor on an internship.

How can digital technology be applied to the sphere of cultural heritage?

Projects implementing 3D-scanned models help museums, galleries, cultural institutions and city cultural departments to realistically visualize their objects and monuments, spread the word about them, engage tourists, and use data for scientific research.

It makes communication between architects and builders efficient, helps calculate the amount of required materials, and can be compared with a scan of the final reconstruction. For damaged structures it is a way to assess the risks, measure the change during time, create maps of destruction. During war and natural disasters, it is a way to document damage before the building is cleared of debris.

For museum exhibits, sculptures, miscellaneous objects, 3D-scanning and other survey techniques are like a doctor check-up before any change the heritage should go through.

The war with Russian Federation brought destruction and damage to Ukraine’s cultural heritage. The future reconstruction of Ukraine will include a huge work of restoration of monuments and historical sites. What added value can Pixelated Realities bring to the process of revitalizing Ukraine’s cultural heritage?

As part of the MOUV initiative we continue to collaborate with the Odesa Department of Culture, Odesa National Fine Arts Museum, Odesa Military Administration (OMA) to collect data about the latest damage to cultural heritage, like the devastating ruins in the city center in July and August 2023, or the rocket that hit at Sofiivska street in November. We collect the data, engage a drone pilot from the OMA, share them with partners for damage assessment and produce materials for projects showcasing Russian crimes.

Today your company is involved in an educational program with prestigious Italian schools of restauration: Opificio delle Pietre Dure (Florence) and Centro Restauro La Venaria Reale (Turin). What is the purpose of this program?

During the first months of the Russian invasion, an initiative called 4CH (European Competence Centre for Cultural Heritage) contacted organizations in Ukraine to suggest back up of their data on the EU cloud. We were able to back up around 30 terabytes of our projects starting from 2016. During 2022 we’ve worked a lot on partnerships with European colleagues to bring resources and knowledge to help local heritage initiatives. We’ve invited 4CH representatives to speak at our final event of the year in Lviv – Forum “Museum of Ukraine Victory” which gathered 50 partners to discuss the role of heritage digitization in Ukraine revival.

In early 2023, we were invited to visit the famous restoration facilities of Opificio delle Pietre Dure (Florence). The trip left a deep impression on us, as we saw in one place how the possibilities of 3D scanning, modelling, printing and casting are used daily to preserve valuable artefacts. Of course, some of the tools there are really incredible and costly, but the contemporary restoration lab is more like a specialized FabLab. It is not cheap, but generally affordable to establish.

Now, we are aiming to launch a collaboration supervised by the 4CH project, and led by INFN, Opificio and their third partner in Italy, Centro Restauro La Venaria Reale (Turin). It is a rather simple idea: we want to bring restoration specialists from Ukraine to Italy to explore the labs and learn about innovative methods of digital heritage analysis. We see it as a great opportunity to plan a gradual development of innovative restoration labs in Odesa and the southern region of Ukraine.

The Italian Government launched a “Patronage of Odesa” recovery plan that includes restoration works on the Cathedral of Transfiguration and other buildings damaged by Russian shelling. What should be the priorities in the selection of buildings?

Our main selection would be The House of Scientists (Palace of Tolstoy), The Palace of Naryshkin-Pototsky (Odesa National Fine Arts Museum), The Palace of Abagi (Museum of Western and Eastern Art) and Palace of Vorontsov. In Odesa the scale of required conservation is enormous. The problems start from the limestone and gypsum material of the buildings, which stand on top of the longest catacombs in the world. This is a port city, a very hot sea resort in summer, but cold and moist in winter, where temperatures can drop to -20, with stormy winds, or 1 meter of snow.

The monuments from 18th and 19th centuries went for decades without the touch of a restorer. There’s a lack of architectural drawings and projects, because some important archives are being stored in Russia or were destroyed during World War II. So, there is not enough data on around 80 percent of the buildings in the historical area. Occasional fires or demolitions caused by nature, catacombs, developers, private owners or homeless people destroy 10 to 15 historical buildings a year in Odesa.

Then add the ballistic rockets to the equation.

How do you see this future cooperation between the Italian experience in restoration of Odesa?

Italy has profound knowledge about the preservation of paintings, frescos, porcelain, glass, stone and wooden decor, sculptures and objects in the authentic state. They make a huge effort to show where a new part was added by the restorer. All of this data is stored digitally as well, and there should be a supporting database and server infrastructure to store it for future use. The research can take from several months only to analyze the current condition of the object. If we want to get help from Italy, we already need to worry about who in Odesa will be able to work together with their researchers, who will accommodate and preserve the results of their efforts.

The city needs to found an innovative restoration entity, dedicated to finding the way to preserve thousands of buildings in danger. We see that without contemporary technology – even without the contribution of unfriendly neighbor countries – Odesa will look quite differently from now. The situation requires strategic vision, sustainable funding, deep research, and conditions for implementing the restoration. But we can start collecting data, producing restoration projects, restoring evacuated art, teaching local professionals, planning the local facility and prototyping even under the rockets.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter