Katerina Anatolevna Semenova is a music teacher in Odesa. She plays the bandura – Ukraine’s national instrument, a sort of cross between a lute and a harp – and has performed in various international and local music competitions. As a teacher, she specializes in solo singing at the Odesa Children’s Music School No. 6, a haven of creativity for children, where highly professional educators try to cultivate the seeds of future culture. Here she tells Kyiv Post about her wartime mission.

How does the system of music schools for children work in Ukraine?

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Music schools as an institution were born during the Renaissance, in Italy. Children in religious orphanages were taught to play instruments, singing, solfège and composition. All of it was born in Italy.

This idea was adopted by the Soviet Union and implemented throughout its territory. There are music schools in every city. In big cities there are many more. For example, in Odesa there are 16 of them. These schools are partially paid for by students, but most of the cost is subsidized by the city. The monthly cost is very affordable: about $10. And some cost even less.

The richer the city, the more it can support these schools. Since Odesa has a very rich musical tradition, we have 16 schools, and for all of them there is a high demand.

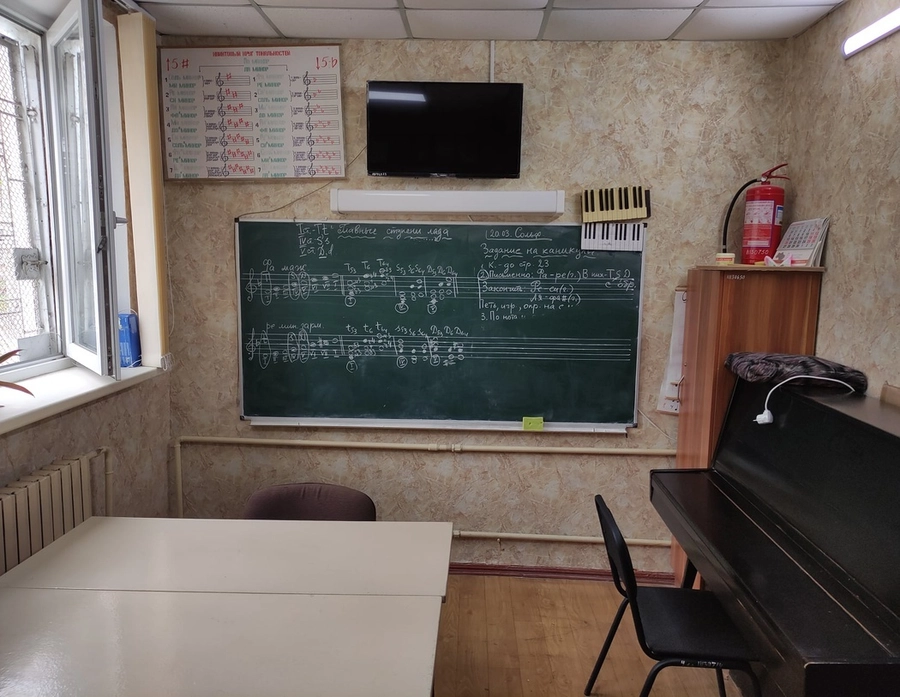

Children learn to play two instruments – piano and bandura, for example – and they sing in a choir. Solfège and musical literature are also part of the program. School begins when a child goes to school in first grade, and he will study for eight years. Within eight years a child receives a good basic education. If he is talented, he can continue his musical education further.

Trump Makes 90 Day Foreign Aid Freeze – Ukraine Military Support Supposedly Untouched

There is the music college, which is a four-year education, in which they improve their professional level as musicians and graduate from secondary school. After the music college there is the conservatory, which is university level. This is a higher educational institution where students receive an even more in-depth musical education, conducting, composition, scores, psychology, and all sorts of disciplines they study while working with children. Students are trained as teachers, soloists, or as orchestral musicians.

What the about Odesa’s music tradition?

Firstly, we know that when Odesa was created, a lot of people from Italy, France, Germany, etc. came here. Progressive people. Our Opera House was built in 1809, when Odesa was only 15 years old. In Kyiv, Opera theatre appeared in 1806, and in 1810 in Poltava. This was a young city, but there was already a theatre.

Musical troupes came here from Italy. Italy brought ballet and opera performances before the Bolshevik Revolution. And people came here to do business from all over the tsarist empire. They had families, they had children to educate. And music was included in the mandatory training program. You weren’t considered a cultivated person if you didn’t knows languages and couldn’t play something or sing.

So, there was a need of good teachers here. And very famous teachers were invited here. Richter, Oistrakh and other world-famous Soviet musicians studied in Odesa. There was the Stolyarsky School here, one of the first in the Soviet Union, which provided a very serious musical education. In the Soviet Union, a lot of music schools were opened, and many children received an education.

What’s happened to your students since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion?

Since the start of the war, music schools have continued to operate. In the first days, there was confusion, of course. People got scared and many with their children were forced to leave. But they didn’t give up studying music. I had 16 students. None of them gave up because of the war. No one. Everyone is learning. Those of my students who went abroad, to Portugal, Spain, Poland, England, Germany, they are still studying online. Regarding the children who remained, we were forbidden to host them in the school premises, because we weren’t ready for a war, we don’t have any bomb shelter.

But students want to make music. Especially young children who have just started learning. How can you teach a child to play the violin online? You can show him how to hold the bow, but you need to touch his hand. Is this a free hand? Does he have right posture? Is the child’s back tight? How does a pianist create sound? He doesn’t just press a key, he has to “bring out” the sound. And it’s virtually impossible to teach this to a child online. You can study online with adults.

We agreed with the children’s parents, and they brought the children to my home to study. We studied even more than we had to, because some lessons were missed due to bombing, or there was no light or no public transport, or it was just very cold. We tried to catch up.

What about the psychological impact of the war on your students?

It’s important to understand: children feel everything. They hear what adults are talking about, who is the enemy, who is the defender. And we must support and guide them. We don’t discuss politics in class. We’re not talking about war. We make music. But children still know everything, they absorb everything. That’s why we choose patriotic songs for our repertoire. We record these songs, make videos and send them to competitions.

For many of my students, someone in their family is fighting. Father, uncle, brother. I have a student whose uncle is serving near Bakhmut. My student came and said: “I want to learn a song about Bakhmut.” And such a song has already been written. It’s called “Fortress Bakhmut.” She and I learned this song and sent it to the competition. The result: we got first place. And my student sent the video to her uncle. Naturally, everyone was happy. That is, children want to make some contribution, however small. Like sending a song to a loved one.

You mention the idea of psychological help to children through music.

At the beginning of the invasion, when many people were confused, they didn’t know how to behave. I have an example with my student’s mother. She called me and said that she hadn’t eaten or slept for four days. I yelled at her and told her to pull herself together immediately. I tried to explain to her that the life of her child depended on her. Decisions need to be made, whether to leave or stay, to run to a bomb shelter; the parent makes the decision.

Yes, everyone is scared, and everyone is stressed, but this does not make it any easier for the child. It’s worse for the child if the mother doesn’t know what to do and sits crying all the time. Or a mom crying to dad at the front. How is the child feeling?

I constantly listened to the recommendations of well-known psychologists on how to relieve stress in children. What needs to be done to bring a child out of a state of horror? We must try to continue normal life. The child must get up, wash his face, brush his teeth, have breakfast, do his homework, practice the piano, and go to class. That is, we should try to keep him in a normal atmosphere, as much as possible, of course.

Because of this war, they say that Russian composers are the music of the enemy. What do you think?

I am categorically against this. Because Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Glinka and all the other Russian composers are a world heritage. They are loved worldwide.

We once fought with Germany. If we did the same, we wouldn’t be listening to Bach, Handel and others. If we base ourselves on the fact that fascism was born in Italy, then we wouldn’t be listening to Vivaldi, Rossini, or any other Italian composer… This is the consequence, if you follow this logic. If we always take a step back, we will give up the richness of the music. Music is a wealth for everyone. But of course we won’t listen to modern Russian propaganda songs. That’s taboo.

Today, there is a huge number of people, refugees, who are under stress. They have a very harsh attitude toward Russian culture and music and they want to ban everything. But I hope common sense will prevail, and people will come to their senses after the end of the war.

How do you see the future of music education?

Now, and especially after the war, we will need to relieve everyone’s stress. Those who return from the front, who were left without a home, and those who have lost loved ones: they all need to be returned to normal life.

How? I propose to open a department for adults at music schools, for those who want, for example, to play the guitar, the piano or learn singing, etc. Perhaps, these people will not become musicians, they will not go to the conservatory. But the fact that this will help them ease the stress of war is 100 percent certain. Because when a person opens up emotionally, he heals the injures within himself. Singing is a conversation with God. That’s what I think.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter