The destruction of the Kakhovka Dam, near Kherson in southern Ukraine, on Monday June 5, which has been fully reported in the world’s media, has echoes of the previous intentional destruction of dams in war time, both in Ukraine and elsewhere. Ukraine is also conscious of the unstoppable forces that are unleashed when even the accidental collapse of a relatively small dam occurs.

The shock that has accompanied the destruction of the dam among Russian troops, who were most likely responsible for its destruction, and Moscow-installed leaders in the occupied areas of the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions is counter-balanced by the fact that, on the Ukrainian side at least, the event had been predicted ever since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

- Access the latest Ukraine news coverage for today.

- Access the latest Ukraine news coverage for today.

- Ukraine War Casualties

For instance, Vitaliy Kim, the governor of Mykolaiv region, which is downstream from the dam, in southern Ukraine, said that evacuation plans were already in existence. A digital pamphlet, with detailed instructions on what to do if flooding occurs, had been prepared in case of such an event, whether accidental or intentional.

“All services are completely ready; we work in close cooperation with colleagues from Kherson and the government. All evacuation points have been deployed, buses routes, everything has been worked out,” he said. “According to the data from the Russian side, they were completely unprepared for the situation, they panic, they flee.”

Zelensky Says ‘Strong’ Trump Can End Ukraine War

Being prepared for such a catastrophe was based on knowledge, forethought and bitter experience of similar events.

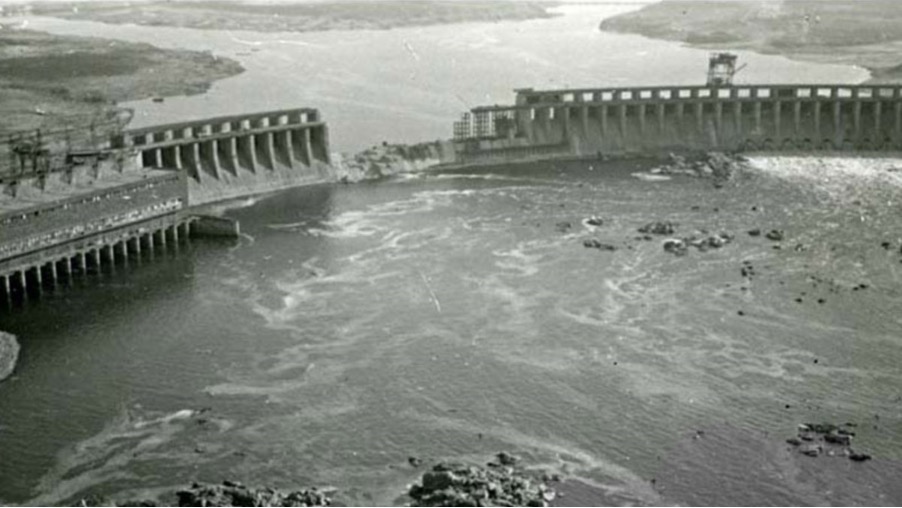

Dnipro dam destruction – 1941 and 1943

In August 1941, Nazi troops swept through Soviet-era Ukraine and were believed to be approaching the southern city of Zaporizhzhia. Moscow – some say, under the direct ordered by Josef Stalin – sent agents from the NKVD (the predecessor of the KGB/FSB) to blow up the city’s DniproHES hydroelectric dam.

The dam, which stood a few miles north of the town of Zaporizhzhia, was 760 meters long and 48 meters high. It raised the river level by almost 40 meters and made the Dnipro navigable over almost 2,000 kilometers by eliminating stretches of rapids.

The aim was to slow the Nazi advance and to deprive German forces access to the electrical power produced by the dam, as well as the large agricultural and industrial areas that existed on both sides of the Dnipro. The NKVD team used almost 20 tons of explosives to tear a 165-meter-long breach in the dam.

Destruction of the Dnipro dam, August 1941

Photo: wikicommons

The destroyed dam released a tidal surge reaching ten meters in height at its peak. It washed away everything in its path, killed thousands of civilians in settlements along the Dnipro, devastating homes and villages along the coastal city strip, Khortytsia island marshes and the neighboring towns of Nikopol and Marhanets. It also killed Red Army troops and destroyed their defensive positions, as they had not been warned of the sabotage plan and, even if they had, would be totally unprepared to protect themselves from the power of the released water.

In echoes of yesterday’s attack on the Nova Kakhovka dam, Moscow disseminated information that claimed it was the Wehrmacht that had blown up the dam – they were helped in this attempted fiction by the several hundred unprepared Soviet troops who died both on the dam and downstream. The Soviets did not keep records of the death toll caused or the extent of the destruction, but based on an earlier census it is believed that as many as 100,000 Ukrainians died. Farms, livestock, homes, factories and hospitals were all swept away. Contemporary accounts talk of people climbing trees to escape the floodwater, only for those to be swept away too.

Historian Vladyslav Moroko believes that, in actual fact, the Germans had no plans to seize Zaporizhzhia at the time and had very few troops in the area. The NKVD team seem to have gone ahead anyway, more afraid of being accused of failing to carry out Stalin’s orders than stopping a German invasion.

Eventually the Germans did take over the area, and partially rebuilt the dam. Two years later, in 1943, as Soviet forces were pushing Hitler’s forces out of Ukraine, Nazi troops blew it up for a second time. At the end of the war, in 1947, the Soviets rebuilt the dam and increased its capacity. It was the first of a string of hydroelectric power stations and reservoirs that the Soviets built on the Dnipro: at Kakhovka, 1958; Kremenchuk, 1961; Dniprodzerzhinsk (Kamianske today), 1965; Kyiv, 1966; and Kaniv, 1973.

The Kurenivka mudslide

Babyn Yar, is a ravine in Kyiv, at the juncture of today’s Kurenivka, Lukianivka and Syrets districts. It was the site of one of the worst Nazi massacres in Ukraine, when over 30,000 Jews were killed in the ravine on September 29-30, 1941, soon after the Nazis occupied the city. Over the following months, they killed a further 100,000 people at the site, including prisoners of war, communists, Ukrainian nationalists, Roma, and homosexuals.

Soviet POWs forced to cover the mass grave at Babyn Yar, October 1941

Photo: wikicommon

Today, the Babyn Yar memorial park stands as an obvious symbol of the Holocaust. But after World War II, Soviet authorities preferred to bury the site, first under a regular landfill, using earth and building debris from the city’s destruction. Later, the massacre site was filled with liquid waste from nearby brick factories, held in place with an improvised earth dam. The plan was to hold the solid waste in place while the while the liquid was pumped out, leaving mud and pulp behind to fill the ravine.

On the evening of March 12, 1961, following several days of heavy rain, the pumping station at the dam failed. At 8:30 a.m. the following morning, the site’s 4-meter high and 20-meter wide earthen dam broke. This released an estimated 4 million cubic meters of slurry that had been dumped into the ravine for more than 10 years. A torrent of pulp sludge, mud, water, and human remains flowed down the steep hill that is the modern Olena Teliha Street and into the city’s low-lying Kurenivka residential district.

It swept all before it, including traffic moving along the streets, burying 68 houses and 13 office buildings, destroying a tram depot, several industrial buildings and a cemetery.

The aftermath of the Kurenivka mudslide 1961

Photo: wikicommons

Needless to say, the Soviet authorities downplayed the scale of the tragedy and imposed a strict regime of censorship. Within hours of the dam breaking, Soviet troops surrounded the perimeter of the flooded areas letting no one in or out.

Recovery operations continued for days, but no official notification of the disaster was published by the Soviet authorities. Military excavators were called in to clean up the mud and debris. As they dug into the slowly hardening slurry they unearthed the body parts of victims, both of the landslide and those from the massacre.

Victims of the mudslide were buried in cemeteries around Kyiv with different dates of death and the official causes of death changed. The official report released at the time claimed there had been only 145 fatalities, but some estimates say that as many as 1,500 people died.

In 1962, the Babyn Yar ravine was leveled off and made into a park. A memorial to Soviet citizens shot at Babyn Yar was erected in 1976, but it wasn’t until September 1991, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, that a memorial to its Jewish victims was built.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter