Are Russia and China allies? At first glance the answer to this question seems obvious.

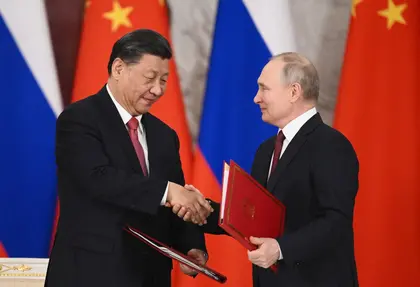

Just this month, that Chinese president Xi Jinping visited Moscow for three days at the invitation of President Vladimir Putin where they toasted each other and appeared to cement the Russia and China alliance and relations between the two nations.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

The Kremlin said that the purpose of the visit was to discuss “issues for the further development of comprehensive partnership and strategic interaction between Russia and China … in the context of deepening Russian-Chinese cooperation in the international arena.”

This seems a natural progression to the joint statement issued by Moscow and Beijing in February 2022, that: “Friendship between the two States has no limits. There are no ‘forbidden’ areas of cooperation.”

But dig a little deeper and it becomes clear that it is far from a relationship of equals, with Moscow increasingly on the back foot next to a far more powerful and influential China.

What is China’s real view of the war?

Experts considered that the meeting was driven by China and Russia’s concerns about resisting continued U.S. global dominance for a world order in line with their own autocratic agendas with little interest in resolving the conflict in Ukraine.

While continue to criticize western sanctions against Russia, accusing NATO of provoking Russia and refusing to condemn the invasion, China continued to declare that the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries must be respected.

Putin and Xi Praise Ties, Hours After Trump Sworn In

A phone call on March 16 between Dmytro Kuleba and Qin Gang, China’s Foreign Minister, it was reiterated that Beijing commended early talks between Kyiv and Moscow to find a political solution. China’s Foreign Ministry stated that China had “committed itself to promoting peace and advancing negotiations and calls on the international community to create conditions for peace talks.”

Mr Kuleba later said that he and Qin “discussed the significance of the principle of territorial integrity” and that he had reiterated the call for President Zelensky to end the aggression and restore a just peace in Ukraine.

China has insisted it remains neutral, has called for a ceasefire and offered to help facilitate peace talks without providing concrete proposals on how to resolve the war. Western nations doubt China’s credibility and impartiality, viewing the ‘plan’ as being more about trying to portray itself as a diplomatic force for good to the developing world. This latest visit by Xi Jinping seems to confirm unspoken support for Russia.

From China’s perspective, Russia’s war in Ukraine is taking the west’s ‘eye off the ball’ concerning China’s wider political ambitions. In addition, Russia’s apparent military failure will serve to increase the political power imbalance between Moscow and Beijing.

Is the China-Russia relationship truly a partnership?

The fact that Russia invaded Ukraine a few weeks after the February 2022 meeting seemed to indicate tacit approval by China of Russia’s actions. A number of western commentators saw this as evidence that the two regimes were about to create an ‘axis of power’, to challenge the position of the United States and its allies, as the foundation of global power and security and to replace liberal democracy as the ideal form of world governance.

However, in the year since Russia’s invasion, rather than the creation of a partnership of equals, China has used Putin’s need for an ally to its advantage, to ensure that Beijing sets the ‘cooperative agenda’ for its own interests.

This change, when viewed in its historical context, further undermines the fear that a Sino-Russian authoritarian alliance was about to pose a united challenge against western democracies.

Fundamentally, in spite of declarations of ‘friendship’, the relationship between China and Russia has been, and some commentators say always will be, one of mutual distrust. Russians have traditionally viewed China as an unsophisticated, largely rural society and overlooked the power that industrial development has given their eastern neighbors.

But now Russia needs help, China is making best use of that neediness. As Russia’s economic situation has deteriorated under western sanctions, China was only too happy to take up the offer of cut-price oil, gas, coal and other raw materials.

Added to the fact that these transactions, which would previously have been conducted in U.S. dollars, are being carried out using the Chinese ‘Yuan’ helps China in its avowed desire to further rival the dollar on international markets.

Russia’s aggression in Europe was an attempt to recover the ‘respect’ it had lost with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The outcome of the war is irrelevant to Chinese interests, it can’t lose.

Xi Jinping, like his predecessors continues to play ‘both sides against the middle’. Beijing’s policy towards Russia is more a reflection of China’s needs and desires to counterbalance Washington’s influence, particularly within its own perceived spheres of influence, than its wish to ‘support a friend’.

So it’s less a case of China and Russia vs NATO, “can China and Russia defeat the U.S?” or an eventual U.S. war with China and Russia, and much more about what both countries are trying to achieve right now on the global stage (though this doesn’t stop some people from speculating on whether or not China and Russia could attack Hawaii).

Whether or not Russian ‘wins’, the Kremlin has burnt its bridges in the west and as long as China does not overtly support Russia militarily, no matter the current poor state of the U.S.–China relationship, it will avoid western sanctions and maintain its global economic position.

In due course the Russian leadership may realize that it has now become more than just the ‘junior partner’ and will have to allow its own political, economic and social agendas to become subordinate to those of China. Will this be any more acceptable to the Kremlin in the long-term?

In the past China has only developed loose bi-lateral relationships and then only with those it is able to control and which directly benefits its own interests. In spite of the rhetoric there is little to indicate that stance has changed in respect of Russia.

In fact, China’s, recently published, ‘Global Security Initiative’ specifically declares that countries should “say no to group politics and bloc confrontation.”

There was little in the statements given by both Putin and Xi to signify that much had changed. The visit was really about economics, the centerpiece of the meetings was the signing of more than a dozen agreements covering cooperation in the usual areas – trade, technology, propaganda.

The leaders’ central statement focused on how the two countries would “deepen” their relationship, promote “multipolar world” and pledged to “safeguard the international system,”. Russia hopes that China will relieve some of the economic damage that sweeping sanctions have inflicted, which China is happy to do as long as it doesn’t impinge on its own relationships with the west.

Both Russia and China may discover, in the not-too-distant future, that neither is actually the good friend they think they are and Russia will find itself with hostile neighbors on all of its borders.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter