Amongst the treasure trove of Ukrainian museums, there is one in Kyiv that stands out for its unique interior spirit andspec

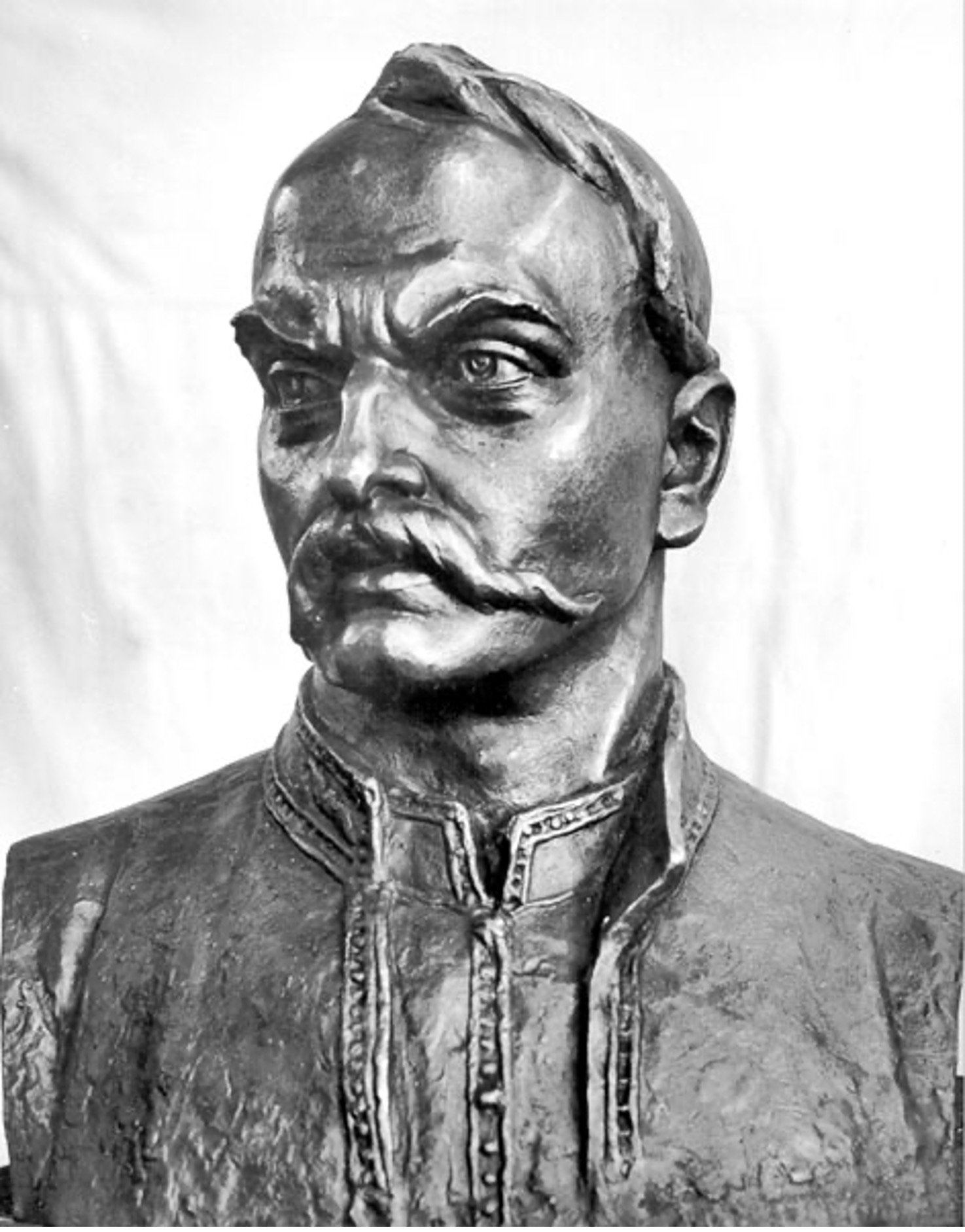

His sculptures stand in many big cities and small towns across Ukraine and his paintings are widely exhibited in this country and abroad.

- Find the latest Ukraine news published as of today.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Honchar was a great artist, but he is remembered and respected above all as a patriot of his nation who had the courage to oppose the Soviet regime, even in defiance of being stigmatized as a “downright bourgeois nationalist.”

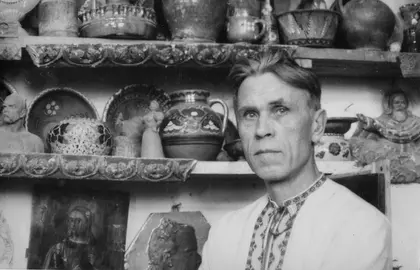

“For all my life I have sculptured, painted, chiseled, cut out wood and paper, traveled, and sung,” he wrote in his autobiography. His biographers wrote that he often replicated forms of folk art and was bold and even daring in creating dynamic compositions and portraits.

Background and upbringing

Honchar was born on Jan, 27, 1911, in the village of Lypyanka, not far from Cherkasy in central Ukraine. Little is known about his childhood, except that his parents were poor and the family could barely make ends meet, especially after the 1917 Bolshevik coup and the Civil War that followed with all the hardships and sufferings. It is known that he loved painting and jumped at every opportunity to express his vision and admiration of his native land in pencil, charcoal, clay or whatever he could use.

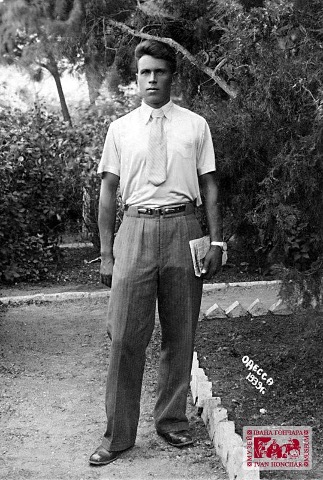

In 1930, Honchar graduated from an art industry school in Kyiv and produced his first notable sculpture. Six years later, he graduated from the Kyiv Institute of Agro-Chemistry. By then,his heart and mind already belonged to art rather than agriculture. While a student, he began to work on a series of sculptural portraits and tried his hand at drawing and painting.And it was then when he became interested in bold forms in dynamic sculptural compositions, and vividly distinct characters in portraits.

Later, his son Petro, now the director of the museum, said: “He was, perhaps, the first sculptor in this country to start searching for new forms in folk painting and one of the first to reveal the artistic value of home icons.”

Lauded sculptor

While working at the Vienna Academy of Arts in 1945, Honchar painted a series of postwar urban landscapes which were commended by art critics for originality and expressiveness.

In his oil paintings, Honchar depicted exemplar Ukrainians as well as landscapes and landmarks of Ukrainian architecture. His graphics mostly featured war themes, but there were also such thematic albums as Ukrainian National Costumes and Historical and Cultural Monuments of Ukraine.

In the first postwar decade, there was probably no sculptor in the USSR more lauded than Honchar, even though he did not sculpture Lenin or other Communist leaders. In 1949, one of his sculptures was bought by the Tretyakov Gallery.

Honchar traveled to the remotest corners of Ukraine and managed to gather a huge collection of ethnic artifacts, some dating as far back as the 16th century.

His brothers helped him a lot, never sparing a ruble to buy folk musical instruments, household utensils and original pieces of embroidery, wickerwork, pottery and other folk crafts for his collection, which he kept in his studio.

In 1957, Honchar set out on his first ethnographic expedition.From then on, he traveled across the country in search of handmade artifacts and collected folk songs and ballads, and explored legends and fairytales, rites and customs. Almost ten years later, he exhibited his collection at his large house indowntown Kyiv, which soon became a popular museum.

A dissident in the eyes of soviet authorities

From the early 1960s, after the so-called “Khrushchev thaw”, and for the last 30 years of his life, Honcha was in opposition to the Soviet authorities that clamped down very hard on any manifestations of what they termed as “nationalistic dissidence.”

His house was a kind of school of national self-identity and self-awareness. The atmosphere created there by material objects of folk art and handicrafts was entirely different from the spirit of Communist ideas imposed on society. It made many people, including young Communist functionaries and apparatchiks, look at life with different eyes and reevaluate their values. The unofficial museum attracted visitors from far and wide while the majority of other museums in Kyiv stood idle.

They closed the museum down, which meant Honchar was in for darker times: left without orders, deprived of decent job opportunities, barred from exhibitions, and practically isolated from the artistic community.

To say that Honchar was disfavored by authorities would be to say almost nothing. He was dangerous to them, and it was only his renown and authority in Soviet and international artistic circles that kept the KGB from locking him up in a jail or mental hospital, like they did to thousands of his fellow-artists.

In August 1965, word spread in Kyiv that Honchar’s monument to the great Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko would be unveiled in the town of Sheshory near the west-Ukrainian regional center Ivano-Frankivsk. Thousands of active patriots went there to attend the unveiling ceremony, but the militia blocked all mountain roads and did not let “strangers” into Sheshory.

Those few who made it to the town learned that the official ceremony had just been postponed for a week. They gathered at the monument for an unofficial ceremony where they sang old Cossack songs and recited Shevchenko’s poems. They had to wind up and leave soon to avoid trouble with the authorities, but news of the event spread across the country and it was remembered as an exemplary manifestation of national self-awareness of Ukrainian pa

The sculptor’s house was a source of inspiration for many artists: having seen Honchar’s collection once, they could no longer drift blindly in the mainstream of so-called “Socialist Realism”.

One of them was Viktor Shkurin, a well-known film director. His visit to Honchar’s house in March, 1966 inspired him to makethe documentary Sonata of an Artist. In the visitor book Shkurin wrote: “No words are enough to express my fascination. Here I saw, heard, and touched the wonderful history of my Ukrainian land. This history must be known to all.”

The documentary was released in a year but very soon was withdrawn from movie theaters. This excerpt from a secret report to the Kyiv regional office of the Communist Party is quite eloquent:

“The documentary by director Shkurin has no clear ideological approach to the assessment and description of historical events. It idealizes the past; it is based on a story of I. Honchar, a sculptor with an evident nationalistic bias…The film features the private collection of old valuables, mostly of casual and ritual character, which I. Honchar tried to use for spreading nationalistic views.”

The film was banned, the director got a dressing-down, and the scriptwriter got his walking papers. That was a warning to others against contacting the disfavored artist.

However, the Ukrainian Society of International Friendship and Cultural Ties managed to send several copies of the film to Canada, the U.S., France and Czechoslovakia where it achieved great success.

Witch hunt

The early 1970s saw the peak of the Kremlin’s “witch hunt” for “nationalists”, “dissidents” and other “renegades”. Honchar and his likeminded fellow-artists went against the grain, so the regime naturally wanted to destroy the atmosphere which they created in the museum.

One day, plain-clothed men came to Honchar's house and insistently “recommended” him to hand his collection over to one of the official museums. They even offered him decent money, but he refused point-blank. Then they resorted to direct threats both to him and members of his family.

They warned everyone of “serious trouble” if they stayed in touch with Honchar. He was under constant surveillance andshadowed, whil

Honchar wrote in his diary: “They kept an eye on me: my mail was read, my phone was tapped, I was shadowed, and I was threatened – both verbally and through the press. For more than 20 years my house was under surveillance. They didn’t only persecute me as a nationalist or dissident. They threatened to burn my house down.”

In 1973, the Communist lobby in the Ukrainian Union of Artists motioned to expel Honchar from the Union and strip him of the Merited Artist of Ukraine title for “spreading anti-Communist nationalist ide

It was down to them that the Communist Party failed to “settle the national issue” once and for all by merging all the nations that inhabited the USSR.

And it was only constant work that helped Honchar to endure those two decades of obstruction and persecution, which ultimately added to his fame instead of discrediting him.

In 1988, when Honchar turned 77, he was finally and duly acknowledged: he had a personal exhibition and got the national Shevchenko Prize. In 1991, when this country gained independence, his 80th

Honchar must have been happy then, but still he was, until his last days, concerned about the fate of his museum which needed an official status and larger premises.

He died on June 18, 1993, and was buried in Kyiv just a few months before the government founded the Ukrainian Center of Folk Culture on the basis of his private collection. This place is now popularly known as Ivan Honchar’s Museum.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter