Russian President Vladimir Putin is unlikely to overcome fundamental structural challenges in attempting to mobilize large numbers of Russians to continue his war in Ukraine. The “partial mobilization” he ordered on September 21 will generate additional forces but inefficiently and with high domestic social and political costs. The forces generated by this “partial mobilization,” critically, are very unlikely to add substantially to the Russian military’s net combat power in 2022. Putin will have to fix basic flaws in the Russian military personnel and equipment systems if mobilization is to have any significant impact even in the longer term. His actions thus far suggest that he is far more concerned with rushing bodies to the battlefield than with addressing these fundamental flaws.

The Russian Armed Forces have not been setting conditions for an effective large-scale mobilization since at least 2008 and have not been building the kind of reserve force needed for a snap mobilization intended to produce immediate effects on the battlefield. There are no rapid solutions to these problems.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

The problems Putin confronts stem in part from long-standing unresolved tensions in the Russian approach to generating military manpower. Russian and Soviet military manpower policies from 1874 through 2008 were designed to support the full mass mobilization of the entire Russian and Soviet populations for full-scale war. Universal conscription and a minimum two-year service obligation was intended to ensure that virtually all military-age males received sufficient training and experience in combat specialties that they could be recalled to active service after serving their terms and rapidly go to war as effective soldiers. Most Russian and Soviet combat units were kept in a “cadre” status in peacetime—they retained a nearly full complement of officers and many non-commissioned officers, along with a small number of soldiers. Russian and Soviet doctrine and strategy required large-scale reserve mobilization to fill out these cadre units in wartime. This cadre-and-reserve approach to military manpower was common among continental European powers from the end of the 19th century through the Cold War.

ISW Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, December 24, 2024

The Russian military tried to move to an all-volunteer basis amid the 2008 financial crisis and failed to make the transition fully. The end of the Cold War and the demonstration in the 1991 Gulf War of the virtues of an all-volunteer military led many states to transition away from conscription models. The Russian military remained committed to the cadre-and-reserve model until 2008, when Putin directed his newly appointed Minister of Defense Anatoly Serdyukov to move the Russian military to a professional model and reform it to save costs following the 2008 financial crisis.[1] One such cost-cutting measure reduced the term of mandatory conscript service to 18 months in 2007 and then to one year in 2008.

The Russian military ended up with a hybrid model blending conscript and professional soldiers. Professional militaries are expensive because the state must offer prospective voluntary recruits far higher salaries and benefits than it gives to conscripts, who have no choice but to serve. Serdyukov quickly found that the Russian defense budget could not afford to offer enticements sufficient to overcome the centuries-old Russian resistance to military service. The Russian military thus became a mix of volunteer professional soldiers, whom the Russians call kontraktniki, and one-year conscripts.

The reduction in the mandatory term of service for conscripts made Russia’s reserves less combat ready. Conscripts normally reach a bare minimum of military competence within a year—the lost second year is the period in which a cadre-and-reserve military would normally bring its conscripts to a meaningful level of combat capability. The shift to a one-year term of mandatory military service in 2008 means that the last classes of Russian men who served two-year terms are now in their early 30s. Younger men in the prime age brackets for being recalled to fight served only the abbreviated one-year period.

The prioritization of building a professional force and the de-prioritization of conscript service likely translated into an erosion of the bureaucratic structures required for mobilization. Mobilization is always a bureaucratically challenging undertaking. It requires local officials throughout the entire country to perform well a task they may never conduct and rehearse rarely, if at all. Maintaining the bureaucratic infrastructure required to conduct a large-scale reserve call-up requires considerable attention from senior leadership—attention it likely did not receive in Russia over the last 15 years or so.

Putin has already conducted at least four attempts at mobilization in the last year, likely draining the pool of available combat-ready (and willing) reservists ahead of the “partial mobilization.”

- The Russian military launched an initiative called the Russian Combat Army Reserve (the Russian acronym is BARS) in fall 2021 with the aim of recruiting 100,000 volunteers into an organization that would train them and keep them combat-capable while still in the reserves.[2] This effort largely failed, generating only a fraction of its target by the time of the Russian invasion in February 2022.

- The Russian Armed Forces conducted an involuntary mobilization of part of its regular reserve in preparation for the invasion and in parallel with the BARS effort. Details about the pre-invasion call-up are scarce, but Western officials reported that the Russian military had recalled “tens of thousands” of reservists to fill out units before rolling into Ukraine.[3]

- A third, smaller mobilization wave followed the invasion itself, as reports emerged of thousands of reservists being called up to make good Russian losses in early March 2022.[4]

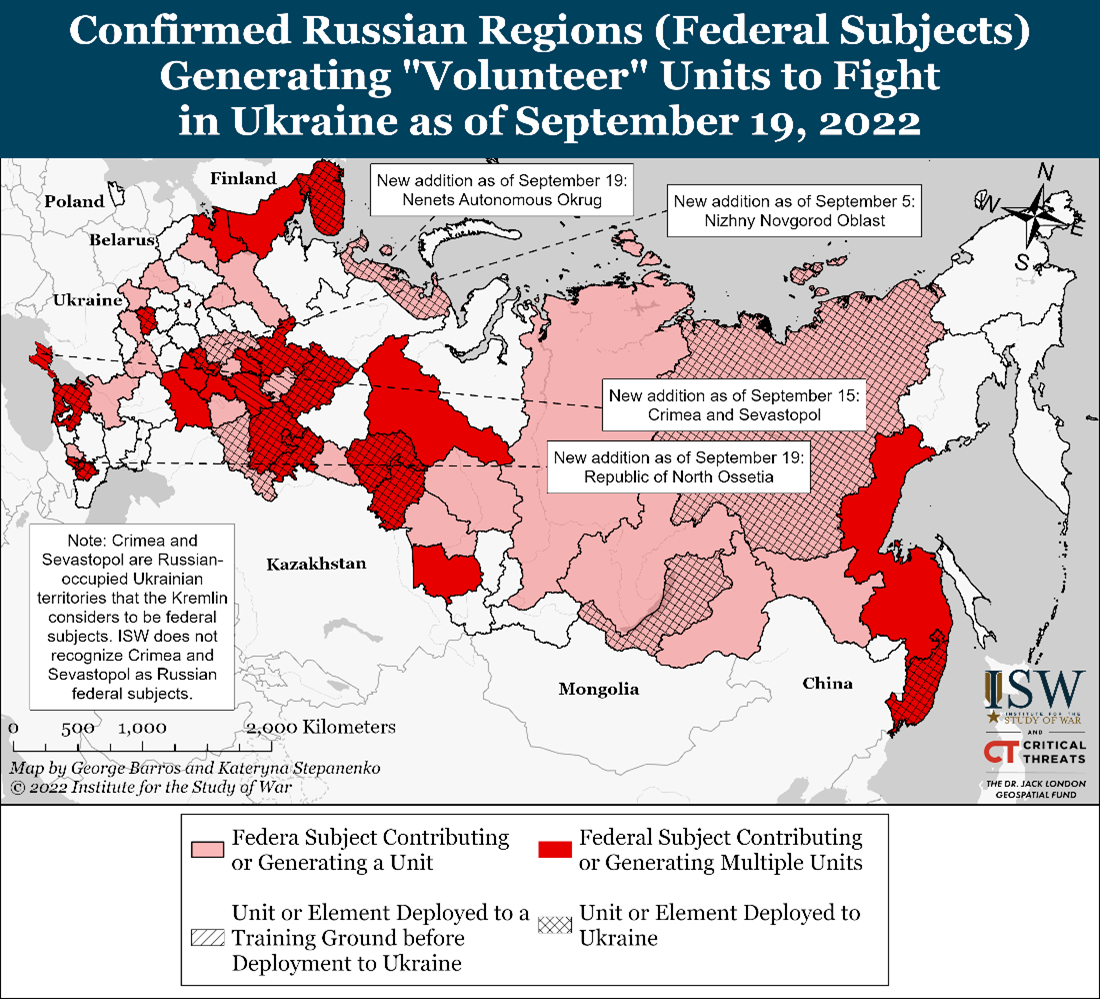

- Putin launched a fourth effort at mobilizing his population for war in June 2022, accelerated in July, with a call for the formation of “volunteer battalions.”[5] This undertaking was an ad hoc attempt at crypto mobilization. The Kremlin directed all of Russia’s “federal subjects” (administrative units at the province level on the whole) to generate at least one volunteer battalion each and to pay enlistment and combat bonuses out of their own budgets. This effort has generated a number of volunteer battalions, some of which have fought in Ukraine, albeit poorly.

The most recent “partial mobilization” will draw mainly on Russians who have demonstrated that they do not wish to fight by their failures to join “volunteer battalions” or enter the BARS program. It may also be drawing on less-qualified involuntary reservists as well, assuming previous involuntary mobilizations pulled in the readiest individuals.

Conducting voluntary and involuntary mobilization efforts simultaneously is likely straining the bureaucrats responsible for these efforts. The military commissars, local officials who actual recruit and call up conscripts and volunteers, were likely responsible for the BARS effort and were certainly responsible for the pre-war involuntary reserve call-up, the smaller reserve call-up after the invasion, and the recruitment of the volunteer battalions. The pre- and post-invasion involuntary reserve call-ups likely helped military commissars exercise general reserve call-up procedures. The subsequent emphasis on generating voluntary recruits, however, likely distracted them from those procedures and forced them to concentrate on an entirely new and unplanned-for effort. The military commissars appear to be tasked now with conducting both efforts simultaneously, as emerging evidence indicates that the formation of “volunteer battalions” is continuing alongside the involuntary reserve mobilization.

The current “partial mobilization” also highlights structural tensions in Russia’s military manpower system resulting from the fact that the Ministry of Defense appears to share responsibility for mobilization with local government officials. The mobilization decree Putin signed on September 21 states that the Defense Ministry establishes quotas and deadlines for reserve mobilization by region, but military commissars are clearly responsible for actually fulfilling those quotas.[6] The commissars do not appear to report to the MoD, however, but are rather subordinates of local and regional political leaders. It is unclear whether statements made by Defense Minister Shoigu about eligibility for exemptions from reserve call-ups are binding on the military commissars—it seems, in fact, that they are not. Shoigu announced in an interview on September 21, for example, that students would not be mobilized, yet military commissars have been mobilizing them.[7] The MoD reportedly summoned military commissars on September 24 to upbraid them for violating its policies, but it seems that Putin had to issue a new decree to explicitly exempt students, which he did on September 24.[8] This confusion has contributed to the anger fueling protests against mobilization and is likely reflective of larger bureaucratic confusion in the mobilization system itself.

Protests and resistance to involuntary mobilization also reflect Putin’s repeated and surprising failures to prepare his population for a major war. Russian senior officials and Kremlin mouthpieces were ridiculing the idea that Russia would invade Ukraine right up to the start of the invasion itself. Putin had made no effort to prepare his population for a war—apparently, even some Russian military personnel involved in the invasion were surprised when what they had thought was a training exercise turned out to be an actual attack. Putin has steadfastly continued to refer to the invasion as a “special military operation” rather than a war, moreover, and has not been setting informational conditions in Russia to prepare his people for this involuntary mobilization.

Putin’s informational failures in this regard are especially important because there are no Ukrainian or NATO troops on Russian soil and no threat of any invasion of the Russian heartland. This is not 1812, 1914, or 1941. The factors that drove popular mobilization in previous Russian wars are simply absent in this aggressive war of choice, however Putin frames it to his people. The World War II example of Russians rallying to the flag is particularly inapposite. The Nazi invasion was a literally existential threat to the existence of Russia and part of an overtly genocidal campaign to enslave those Soviet citizens it did not kill. The current conflict is as far from that reality as any war could be, and no rhetorical sleight of hand can replace the brutal realities of the Nazi armored advances as a spur to fight.

Russia will mobilize reservists for this conflict. The process will be ugly, the quality of the reservists poor, and their motivation to fight likely even worse. But the systems are sufficiently in place to allow military commissars and other Russian officials to find people and send them to training units and thence to war. But the low quality of the voluntary reserve units produced by the BARS and volunteer battalion efforts is likely a reliable indicator of the net increase in combat power Russia can expect to generate in this way. This mobilization will not affect the course of the conflict in 2022 and may not have a very dramatic impact on Russia’s ability to sustain its current level of effort into 2023. The problems undermining Putin’s effort to mobilize his people to fight, finally, are so deep and fundamental that he cannot likely fix them in the coming months—and possibly for years. Putin is likely coming up against the hard limits of Russia’s ability to fight a large-scale war.

Author: Frederick W. Kagan

See the full report here.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter