Thinking outside the box

The year was 1987. The ice of the Cold War had begun to melt, and the United Nations Secretariat, an ever-subtle political thermometer, sensed an opportunity to engage in previously “unsolvable” issues, such as Afghanistan or apartheid.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

One morning my first UN boss, Mr. Harbachan Singh — in his previous life a tough Malaysian police officer — looked even more serious than usual: “Your task will be to check every UN commercial partner to make sure that they are not connected to the Government of South Africa in any way. You can’t afford to make any mistakes.”

- Access the newest Ukraine news items published today.

- Russian Losses

Obviously, there was surprise written on my face — going through Dun and Bradstreet records of countless UN vendors in search of some ephemeral connection sounded like a glorious wild goose chase for the rest of my UN life. But Mr. Singh was not to be dissuaded: “The GA has put the apartheid regime under sanctions. Not just the Security Council, but the whole General Assembly. Their decision may be nonbinding, but every capital in the world is watching how we, the Secretariat, are handling their advice.

”So please start by reading this guidance, and be very thorough.” He gave me a yellowed Xerox copy of the United Nations GA Resolution 1761 of November 6, 1962, and off I went to the Dag Hammarskjold Library to work on yet another little brick to be laid in the wall restraining the racist regime.

Putin to Meet UN's Guterres for First Time in Over Two Years of War in Ukraine

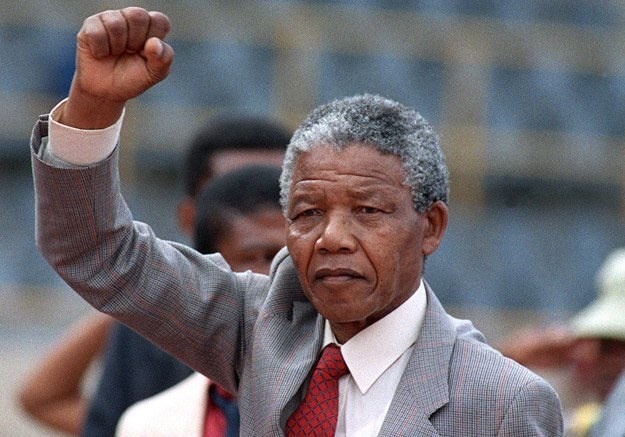

International solidarity resulting in the gradual isolation of Pretoria worked: In 1993, on the eve of black majority rule in South Africa, Time magazine asked Nelson Mandela if economic sanctions against the country helped speed the demise of its apartheid system. “Oh, there is no doubt,” Mandela replied.

Landmarks still very relevant today

Today, as we are about to mark the 60th anniversary of one of the most influential UN documents, it may be appropriate to consider what lessons drawn from anti-apartheid diplomacy can be used to better prosecute the latter-day international pariahs: Russian aggressors.

Due to the right to veto, in both situations — apartheid and the Russian invasion of Ukraine — the Security Council, as the only UN organ whose decisions are enforceable, failed to fulfill its role under Article 39 of the UN Charter to address issues related to “threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression.” Uniquely, in these two instances the GA took upon itself the role of the Security Council. Resolution 1761, reaffirming that Pretoria’s racist policy “seriously endangers international peace and security,” urged the abandonment of apartheid. Resolution ES11/L.1, “Aggression Against Ukraine,” adopted by the GA Emergency Session on March 2, 2022, deplored Russia’s invasion as a violation of the UN Charter and demanded, inter alia, full withdrawal of Russian troops. Both resolutions, separated by almost 60 years of UN history, will undoubtedly go into diplomatic handbooks as landmark documents.

In total, since its creation in 1945, the UN has adopted over 80,000 resolutions: It would be counterintuitive to try to compare even the most notable of them in either importance or effectiveness. Nonetheless, considering the unique nature of 1761 and ES11/L.1, let’s ask in layman’s terms which document seems to be better fit for the stated purpose of overcoming the threats to peace and security.

The phrase that comes to mind when reading the Ukrainian resolution, which received an overwhelming 141 votes in the GA, is “diplomatic fireworks.” Collective diplomacy managed to translate shock, pain, indignation, and anger of the first week of brutal aggression into a compelling narrative highlighting Russian lawlessness and sending Moscow a message: “STOP NOW.” Unfortunately, in the absence of Security Council support, the resolution stopped short of saying “OR ELSE,” i.e., it is missing a punitive part. In this respect, ES 11/L.1 is about crime without punishment.

On the other hand, looking in retrospect at the 1761, it becomes clear that, while lacking some emotional flair, the anti-apartheid text was designed and worked as a time bomb triple-charged with the following elements: recommending a specific list of sanctions, setting up a permanent anti-apartheid oversight body, and leaving space for the future Security Council involvement.

Details elaborated

The list of recommended “voluntary” sanctions is self-explanatory and deserves to be cited here in full:

(a) Breaking off diplomatic relations with the Government of the Republic of South Africa or refraining from establishing such relations;

(b) Closing ports to all vessels flying the South African flag;

(c) Enacting legislation prohibiting ships from entering South African ports;

(d) Boycotting all South African goods and refraining from exporting goods, including all arms and ammunition, to South Africa;

(e) Refusing landing and passage facilities to all aircraft belonging to the Government of South Africa and companies registered under the laws of South Africa.

In order “to keep the racial policies of the Government of South Africa under review when the Assembly is not in session,” the 1761 recommended establishing a Special Committee of Member States.

Finally, the GA requested the Security Council “to take appropriate measures, including sanctions, to secure South Africa’s compliance… and, if necessary, to consider action under Article 6 of the Charter.”

To recapitulate, in 1962, the General Assembly, acting on its moral authority, managed to create an effective international mechanism of prosecuting and monitoring the rogue state. The important traits of the 1761 were that it was actionable and, through inviting the Security Council, potentially enforceable. Over the course of three decades, the time bomb of the 1761 undermined the foundations of apartheid — and the regime collapsed.

The above comparison is not meant to diminish in any way the significance of ES/11L.1. Its adoption has been a major diplomatic achievement for Ukraine and the world. However, it is worthwhile keeping in mind that the GA Eleventh Emergency Session has not been terminated yet: It was adjourned and is still in session.

Possibly, rather than investing time in fruitless dueling with Ambassador Nebenzya’s “Greatest Show on Earth” in the Security Council, Ukrainian diplomacy may become even more productive by engaging the General Assembly, particularly on issues of universal concern such as nuclear security and safety. After 60 years, Resolution 1761 is a good sample of diplomatic tools available to a skillful multilateralist.

The most natural step upon passing the anti-apartheid GA resolution would have been expelling Pretoria from the United Nations. However, diplomacy is the art of the possible: It took 12 years, until November 1974, to suspend South Africa from participation in the General Assembly. The GA overwhelmingly voted to uphold a ruling by the assembly’s president, Foreign Minister Abdelaziz Bouteflika of Algeria, not to recognize the credentials of the South African delegation.

The decision was without precedent in United Nations history, but it did not exclude the South African government from membership itself (the formal expulsion or suspension would have required a Security Council recommendation – a nonstarter in this case). It meant that the delegation was not permitted to take its seats, speak, make proposals, or vote. The proof of the brilliant elegance of Bouteflika’s move was the fact that for two decades, year after year, until the end of apartheid, the GA consistently rejected South African credentials, effectively blocking its UN membership.

In case of the Russian aggression, as soon as the full-scale invasion started, some experts were advising to use the anti-apartheid precedent and try to withdraw “Putin’s credentials” at the GA Emergency Session on Ukraine.

Unfortunately, the idea did not gain traction at the time; instead the Ukrainian diplomacy concentrated on a different track: declaring that Russia was not a bona fide member of the Organization, since there had been no decision admitting it as a member after the demise of the USSR.

What’s missing

Without going into detailed analysis of this strategy, rightfully flagged by the renowned lawyer Professor Larry Johnson as a rabbit hole, it should be noted that the démarches on the legality of “continuing state” are late by some 30 years. Working with a credentials committee and the GA presidency (this year Hungary) may be more productive; if not in getting the Russians suspended, then at least creating a long-term political discomfort factor for their delegation.

As is always the case with idealistic, groundbreaking initiatives, both Resolutions, 1761 and ES/11L.1, had to make their way through the maze of realpolitik. For example, the Nixon-Kissinger policy with regard to the white-minority governments in southern Africa (Portugal in relation to Angola and Mozambique, Rhodesia, and South Africa) was based on the presumption that apartheid and colonial rule were unpleasant but undeniable realities, and that Washington should accommodate itself pragmatically to the status quo. Thus, if the United States was to be an influence for enlightened change, it must do so by offering the carrot and eschewing the stick.

In the same vein, ever since Russia annexed the Crimea and unleashed the war in Donbas in 2014, the Kissinger-style see-no-evil diplomacy is back in circulation. As the war drags on, the voices of putinverstehers (Putin sympathizers) in the UN are getting louder. Reuters recently quoted a senior Asian diplomat saying, on condition of anonymity, “Support will wane because the March resolutions represent a high watermark; and there is no appetite for further action unless red lines are crossed.”

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated view. Russian diplomacy is working hard to derail the organization. Indifference to moral considerations, destruction of ethical values, weaponized propaganda is the model UN of Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov and the Russian representative to the UN Nebenzya.

Navigating through adversity requires strong moral leadership. The UN Secretary-General is often called the secular Pope because his position permits him, indeed compels him, to speak on behalf of all women and men from a position of moral authority. Throughout history, the Secretaries-General appreciated the need to personally interfere in the most difficult situations of war and peace: Dag Hammarskjold sacrificed his life on a visit to the Congo; Boutros-Ghali showed courage in traveling to besieged Sarajevo; Kofi Annan flew to Baghdad to preempt the war. These are just a few examples.

In this context the good offices of Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, in seeing the grain deal through, undoubtedly deserve respect. At the same time, it is hard not to notice considerable frustration among Ukrainians who feel that the UN has deprioritized its main mission of stopping the war in order to secure the functioning of supply chains.

Take for example the latest meeting of the Security Council on the agenda item “Maintenance of Peace and Security of Ukraine.” Listening to the Secretary General’s remarks, the statistics were as follows: the word food was used 12 times, fertilizers five times, and grain six. On the other hand, peace merited four mentions (only as a wish on Ukraine’s national holiday), security three. One of the old colleagues asked in disappointment, “Is he running for the FAO job?”

The tone at the top informs behavior on the ground. How else can you explain the recent misunderstanding with the newly appointed UN country coordinator, who, upon observing the Russian strike of a civilian train in Chaplyne, commented with equanimity of a tennis umpire that all parties must abide by the laws of war. Such evenhandedness in front of fresh graves of 25 civilians, including three children, benefits nobody but the aggressor.

What the UN should do

In the absence of clear guidance on sanctioning the culprits, as was done in the case of apartheid, what can the Secretary-General do to ensure that the Secretariat indeed takes a stand maintaining the UN Charter and the highest standards of integrity? Here are several suggestions of what actions can be taken solely within the SG authority.

- Take a harder look at the senior leadership team of the global UN Secretariat,e., the group of the UN executives composed of the so-called political appointees recommended by their national governments.

Routinely, in choosing these individuals for the cabinet positions, a Secretary-General takes into consideration many factors including geopolitical reasons. For example, it would have been untenable to appoint a secondee of the apartheid regime to a human rights job. Equally unthinkable would have been the selection of a North Korean functionary as an executive director of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

However, surprisingly, the appointees of the aggressor-state maintain their senior positions at the Secretariat irrespective of Russia turning into a pariah regime. For example, a secondee from Lavrov’s foreign ministry whose main task these days is whitewashing Russian terror practices keeps his job as an under-secretary-general for counterterrorism.

Another Russian appointee is employed at a high position of assistant secretary-general in peace operations, directly supervising the UN Mine Action Service — the unit responsible for the de-mining program in Ukraine. Equally absurd and embarrassing is the fact that a Russian representative continues to occupy a post of the deputy director general of IAEA in charge of nuclear power plants. None of these officials have been selected solely on their merit — all of them are political appointees of the aggressor-state and must be regarded as such.

- Stop financing Russian aggression through UN business opportunities such as UN procurement. After human resources, the acquisition of various goods and services, amounting to over $30 billion per year, is the largest expense item in the UN family. Russia has positioned itself as one of the main purveyors to the UN: The procurement portal, ungm.org, shows the presence of 1,396 Russian vendors registered to compete for the UN contracts. Since Russia unleashed the war in Ukraine in 2014, it has been awarded UN business in the amount of over $2.8 billion, including $282 million in 2021.

Against the background of global economic sanctions, such generosity is baffling, to say the least. The UN Secretariat has done nothing to replace Russian vendors like it did in the case of buying from apartheid. As a victory for Moscow extortion diplomacy, procurement from Russia figured prominently in a secret side deal to the grain agreement signed by the SG in Istanbul.

The well-informed Passblue news company noted this connection: “The section in the agreement on the UN advising Russian companies on ‘how to do business with the UN and the procedure and requirements for becoming a registered vendor’ is another confounding aspect of the plan. It seems intentionally written to include any Russian vendor — rather than only food- and fertilizer-related — into the UN procurement system, thus trying to pre-empt further requests by Ukraine and its allies to stop buying Russian goods and services.”

- Stop chartering Russian aircraft. The UN peacekeeping and humanitarian operations rely heavily on Russian aircraft, primarily Mi-8 helicopters, that have been chartered from Russian commercial companies. Currently, 62 Russian-registered aircraft are flying under UN call signs for peacekeeping (45) and the World Food Programme (17). The cost of their services in 2021 amounted to $181 million.

In a confidential Note sent to the SG at the onset of the Russian invasion, the head of the Department of Operational Support (DOS) referred to “some informal demarches to stop contracting aircraft from the Russian Federation.” He insisted, however, that without “the aviation services of operators from . . . the Russian Federation, our global peace operations will come to a halt.” He added, “I am not hopeful that we will be able to fill such a large void within a reasonable period of time” – a remark that put any action against Russians on the backburner.

In the meantime, Moscow has sidestepped aviation-related sanctions by passing a domestic law on March 14, 2022, allowing Russia to add foreign aircraft leased by its aviation industry to Russia’s own national registry. The move by Moscow essentially meant repossessing nearly 700 Western aircraft. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) responded by calling on Moscow to immediately cease its infractions of international aviation rules. The ICAO decision referred to the violation of Ukraine’s sovereign airspace in the context of Russia’s war of aggression, and to the deliberate and continued violation of several safety requirements in an attempt by the Russian government to circumvent EU sanctions. Those actions include illegally double-registering in Russia aircraft stolen from leasing companies, and permitting Russian airlines to operate these aircraft on international routes without a valid certificate of airworthiness. ICAO has given Russia until September 14 to resolve the warning.

Placed on a collision course with its own aviation agency, the UN bureaucracy has finally started moving: The heads of DOS and WFP warned the Secretary-General of planning for the worst-case scenario and fleet replacement. In late August, the UN issued pre-tender documents for helicopter services. It is unclear what can be done before the ICAO deadline of September 14, but it is definitely a welcome move. However, let’s not forget that this positive development is driven by a technical reason against the existential background of Russia’s shooting down a Malaysian airliner, disrupting and endangering international airspace and navigation routes, and bombing airports, all of which violate the Chicago Convention on Civil Aviation.

- Divest from Russia. The Secretary-General has fiduciary responsibility over the $86 billion UN Joint Staff Pension Fund (UNJSPF). According to the latest available statistics (2020), 1.09 percent of the fund’s assets, or $783 million, represented the Russian portfolio. More recent reports indicate that UNJSPF has begun divesting from Russia. However, this is not to sanction the aggressor-state but because the Russian economy is relying on fossil fuel. Since UNJSPF is a signatory of the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), it is logical to expect that it will fully apply ethical considerations to its Russian portfolio and finally make a public statement on divestment from Russia, as various government pension funds worldwide have already done.

- Stop receiving Russian money as voluntary contributions toward UN causes. The UN Development Programme recently accepted $14 million in funding for climate-related projects in Europe and Central Asia. The final document in a series of four agreements was signed in March, when the Russian massacre in Ukraine was at its bloodiest stage. A significant part of funds has been earmarked “to address and manage marine litter and plastics in the Caspian Sea.” The Russian diplomat who landed the deal on UNDP must be laughing, since Caspian Sea is the main launchpad of submarine-based Kalibr cruise missiles that are hitting Ukrainian cities every day.

In a nutshell, there are a plethora of actions which can be taken to prosecute international pariahs. If the stakeholders have political will to do the right thing, the toolset of multilateral diplomacy is very rich. However, if there can be only one takeaway from Resolution 1761 and anti-apartheid diplomacy, it is as follows: “Dear United Nations, your charter has been blatantly violated. Please stop doing business as usual.”

Postscript

Nearly 35 years have passed since Mr. Singh gave his trainee a memorable anti-apartheid assignment. That racist regime has since fallen, and the international community has proceeded to face new challenges. On the morning of February 24, 2022: The big war started half an hour ago. I felt anger, anxiety, despair, and emptiness. My phone rang. “This is Mr. Singh. I’m calling to tell you that the whole world is with your country. Ukraine will win and the aggressors will be punished — I know this for sure.” I felt a lump in my throat. The voice of the old man was feeble, but nobody in their right mind would question his authority: Mr. Harbachan Singh, a tough Malaysian cop, a UN veteran, and a decent human being, knew what he was talking about: the power of solidarity.

Dmytro Dovgopoly is a former UN staff member (1987-2019)

The view expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily of the Kyiv Post.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter