While the US President, his Secretaries of State and Defense and NATO leaders are regularly quoted about their views of the war, what are the deeper currents of thought among Western policymakers and thought leaders? In short, what advice are the political leaders getting?

No one has a perfectly clear window into the mind of the foreign-policy establishment in America. But you could do worse than to listen closely to the specialist monthly Foreign Affairs.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

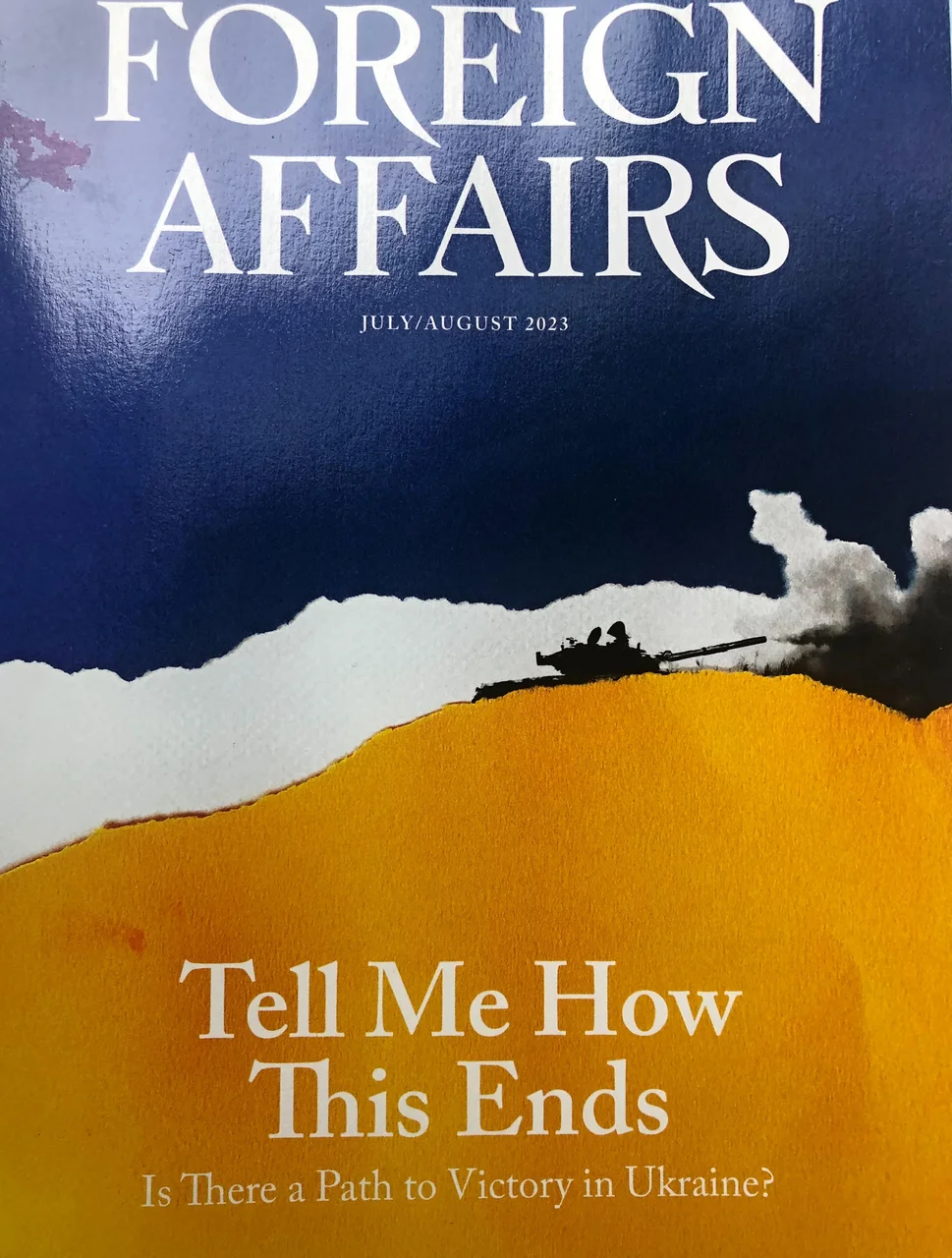

Its July-August special issue on Ukraine, titled “Tell Me How This Ends: Is there a path to victory in Ukraine?” includes three major articles by foreign-policy experts and government advisers. There are also related commentaries about the difficulties of political change in Russia and new threats to European security. These views may influence Western policies.

Nobody will be happy

The FA issue reaches no solid consensus: one expert toys with the prospect of a Ukraine breakthrough in the east, but then retreats to conclude it is “An Unwinnable War.” Another writer evokes the history of warfare and how it can spin out of control, drawing in more combatants and expanding against everyone’s best interests, as in the First World War.

One theme recurs: nobody will be happy with this war’s outcome. Negotiations, however discreet or indirect, need to start immediately and to continue even during fighting. These could lead to an armistice, after secondary issues are settled.

Putin Orders AI Cooperation With China

Samuel Charap, a senior analyst at the RAND Corporation and former State Department official in the Obama administration, is author of the Unwinnable War piece, subtitled “Washington needs an endgame in Ukraine.” He begins by stating that “while the Western response was clear from the start, the objective – the endgame of this war – has been nebulous.”

“It is now time that the United States develop a vision for how the war ends… If the [US and its allies] decide to wait, the fundamentals of the war will likely be the same,” but the human costs will have multiplied. Charap adds that a protracted war can continue indefinitely with no progress, noting that the Iran-Iraq war dragged on for eight years. Such a situation allows, and even demands, military escalation.

He predicts: “The war will end without a resolution to the territorial dispute. Either Russia or Ukraine or, more likely, both, will have to settle for a de facto line of control that neither recognizes as an international border.”

Charap cites as precedent for this “unsatisfactory outcome” the Korean War armistice of 1953. Nobody got what they wanted, but all parties were constrained to accept it anyway. He notes, however, that the military option predominates within the US government: the Security Assistance Group-Ukraine military command there is led by a three-star general with a staff of 300. “Yet there is not a single official in the US government whose full-time job is conflict diplomacy,” laments Charap.

The Korea analogy gets a lot of attention in Foreign Affairs. Carter Malkasian, chair of defense analysis at the Naval Postgraduate School, gives a detailed account of that 1950-1953 war in his piece “The Korea Model: Why an armistice offers the best hope for peace in Ukraine.” He notes that the Soviet Union and the US faced off indirectly in that war, each giving enemy sides military and diplomatic support. The threat of nuclear escalation remained visible throughout the conflict.

Soviets became less dogmatic

Those similarities cannot obscure the many differences. US and other allied troops, British and Canadian, fought under the United Nations flag alongside southern Koreans; it was called a “police action” against aggression. China fielded troops in Korea, while the Soviets did not.

Negotiations began after a year of conflict. The UN channel was always open for talks after 1951, encouraged notably by Indian diplomat V.K. Krishna Menon.

In 1952, legendary US general Dwight Eisenhower was elected President. This stiffened American resolve. Perhaps more important, in March 1953 Joseph Stalin died; the Soviet positions became less dogmatic. By June, negotiations focused more seriously on practical and short-term issues, such as the return of prisoners of war.

Gradually, it became a forum for more concrete discussions of how to end the conflict by dividing territory. But nothing was easy: “The Communists wanted the 38th parallel to serve as the cease-fire line. The United States, on the other hand, preferred the frontline (or “line of contact”), which was slightly north of the parallel, where the rugged terrain was easier to defend. On November 27 [1953], after four months of talking and fighting, the two sides agreed that the line of contact would become the cease-fire line,” writes Malkasian.

That line somehow holds today, 70 years later. And there is still no formal end to the war. But North and South Korea have gone on as separate, sovereign States in an unsatisfactory equilibrium.

The most pessimistic take in Foreign Affairs is contributed by historian Margaret Macmillan. An Oxford scholar, she is famed for her account of the 1919 Versailles Treaty that concluded the First World War. Her article, “How Wars Don’t End: Ukraine, Russia and the lessons of World War I” focuses on how unpredictable and volatile wartime developments can be. In 1914, many in France expected a quick end to the border war with Germany, and to be “home for Christmas.” That wasn’t to be, as the two sides dug in for years, made no progress, used prohibited weapons and decimated their societies.

“In 1914 and 2022 alike, those who assumed war wasn’t possible were wrong,” she notes.

She compares Putin’s idea that Kyiv could be rapidly conquered in 2022 to the Schlieffen Plan of Germany, which foresaw its troops quickly running through Belgium to encircle Paris – “all within six weeks.”

Macmillan underlines, too, that “symbolic” battles can overshadow any real military objectives; many First World War battles raged around areas such as Verdun, which she compares to Bakhmut in 2023. Holding those sites was critical to morale, but perhaps less so strategically.

Macmillan stresses the importance of early and ongoing negotiations in war. Even at the worst of times, they can prevent miscommunication and disaster. And humiliating an enemy is not the end of conflict; the postwar peace must be won, too.

While some of these views may seem wrongheaded or naïve to embattled Ukraine leaders, it is worth noting that they may soon be the consensus opinions in Western capitals.

The views expressed are the author’s and not necessarily those of Kyiv Post.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter