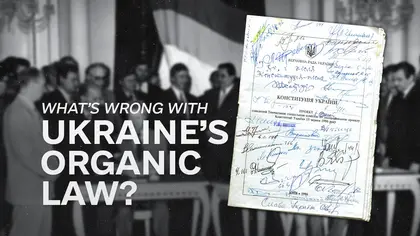

June 28 is Constitution Day in Ukraine, which marks the anniversary of its adoption by the Verkhovna Rada in 1996. Since then, Ukrainian politicians have constantly described the Organic Law as one of the best and most democratic in the world, but have rewritten it more often than the Ukrainians have elected their presidents.

Ukraine’s Constitution has been amended nine times: in 2004, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2019 (twice), and 2020. The amendments were mostly intended to correct or eliminate shortcomings, but they, in turn, often generated new ones instead. We remember Viktor Yushchenko’s presidency as being marked by several attempts to usurp power through amendments to the Constitution.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

The first attempt was made in 2004 by the then prime minister Viktor Yanukovych who poached deputies from opposition factions in order to beef up the pro-government coalition. He would have succeeded in garnering 300 votes (the required constitutional majority), had Yushchenko not stopped him in 2007 by dissolving parliament.

Then there was the constitutional reform of 2004 that made Ukraine a parliamentary-presidential republic with the Rada being vested with more political powers. While it retains those powers, but some of the provisions in the Constitution allow the president to chisel away at the lawmaking process in favor of his own political purposes. For example, the president has the right to prioritize the consideration and adoption of draft bills which he tables, while the Cabinet of Ministers does not have this privilege.

‘We Are Blocking Propagandists’ – Zelensky Imposes Sanctions on Pro-Russian Politicians

Some of the provisions are vague or even contradictory, which often leads to conflict within the President-Parliament-Government triangle. That may be one of the reasons why some Ukrainian presidents have abused their personal right to table amendments to the Constitution. All of the amendments adopted over the last several years were initiated by the head of state and set up their own extra-parliamentary teams to develop constitutional reform. Petro Poroshenko, for instance, set up the Constitutional Commission and Volodymyr Zelensky the Commission on Legal Reform.

What about stable democracies? How often are their constitutions “rewritten”?

In Australia, for example, for an amendment to be adopted it has to be supported by the majority of voters in the majority of the states. Switzerland has a similar procedure. In both countries, the ultimate decision is made by referendum. In the United States, whose constitution was amended very many times in the earlier periods of its history, a joint resolution by the Congress is enough.

Unlike in these stable democracies, the Ukrainian Constitution of 1996 has long been perceived as its fundamental law rather than a contract between the authorities and society. Subsequently, the latter’s trust in the Constitution is still rather low as the people regard it as an imposed law which the country’s leadership can change at its own discretion. Regrettably, this problem will be there as long as the lawmakers retain the authority to make amendments to the majority of the articles without substantively discussing their content with society.

The Constitution of Ukraine shall not be amended while the country is in a state of war, but most politicians and experts already predict there will be amendments right after the war. It is obvious that there need to be changes to bridge the numerous gaps and eliminate the duplications of legal norms that the war has exposed.

The Ukrainians have always valued, cherished and defended the fundamental human rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution. And it is for them that the best sons and daughters of Ukraine are fighting and sacrificing their lives.

The views expressed in this opinion article are the author’s and not necessarily those of Kyiv Post.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter