Two major fallacies continuously infect Western analyses about China’s perspective on Russia’s war in Ukraine:

1) that China supports Russia, and

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

2) that the West cannot afford to waste resources on helping Ukraine when the real long-term threat is China.

The first fallacy leads to a standoffish approach to China concerning Ukraine when we should instead be seeking to enlist China in support of Ukraine’s sovereignty and economic development, while disincentivizing any temptations to take Russia’s view on the conflict.

The second fallacy implies we should diminish Western support for Ukraine — something that would only serve to encourage China in its ambitions to take Taiwan, and thus increase the costs to the West in any future conflict there.

Why do we fall into these traps? Because we look at Chinese actions or inactions through the perspective of our own wishes and fears, rather than China’s. The starting point for thinking about China’s policy concerning Russia’s war against Ukraine is Chinese interests. These are complex and do not fit neatly within the dividing lines of Western policy thinking.

Most importantly, China believes it is a rising power that will achieve a globally dominant position within the next several decades. It does not need to act in haste, because time is on its side. It does not need to act in fear, because its power is growing while the rest of the world’s strength diminishes. It does not need to court others, because others will be attracted to China’s growing power regardless of its actions. It deeply believes that Taiwan is a part of China — recognized by the rest of the world through the One China policy — and it is only a matter of time before Taiwan is under Beijing’s control, as is already the case with Hong Kong.

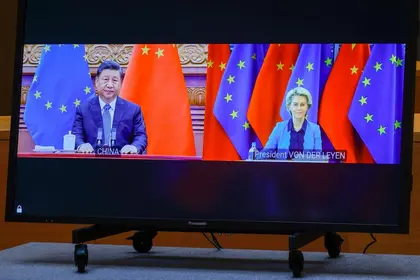

China, EU, Ukraine Leaders Take Davos Stage Under Trump Shadow

This could not have been more clearly on display than in President Xi’s visit to Moscow in March. It was clear from the speeches as well as the body language that China views Russia as a dependent and inferior partner. It does not need anything from Russia that it cannot buy with cash, which Russia desperately needs. Yet Russia also craves at least the appearance of greater political and military support from China, which China has no interest in giving. Indeed, holding back actually gives China leverage in negotiating better deals with Russia.

Part of this Chinese thinking is not only transactional but about values. China does not respect Russia, because the Kremlin does not take care of the Russian people or the Russian state. China cares deeply about its people — not as individuals, but as a society. It strives to lift them out of poverty, improve education, infrastructure, health care, the environment, and security. It invests to become the leader in global technology innovation. China is serious about its society, even if it oppresses individuals who fight for freedom and democracy against direct government control. Russia does not invest in its own society at all, and China sees this decline and believes it works to China’s advantage.

A further element in Chinese policy is in shaping global opinion about its ambitions to absorb Taiwan. China assiduously defends state sovereignty and territorial integrity because this aligns with its position that Taiwan rightfully belongs to the government in Beijing. Most countries accept this through their One China policies. China vigorously pushes other nations in the world to recognize the government in Beijing and not Taipei. Supporting Russia in denying sovereignty and territorial integrity to Ukraine — which Russia had previously recognized as an independent state, within its agreed borders — would be antithetical to Chinese interests.

China wants to see Western global economic and political leadership diminished. Russia’s all-out invasion of Ukraine has produced the opposite effect: The West is more united and active than it would have been if Russia had not invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

China has far greater economic interests in Europe and the United States than it does in Russia. (Trade with Russia has soared since the all-out war began, but combined US and European trade with China is at least 10 times greater.) Of course, China will do business with Russia if it is profitable and does not risk Western sanctions. But if it comes to a choice between Russia and sanctions, China will choose to do business with the West.

China is slightly alarmed that Russia is destroying Ukraine, and committing heinous war crimes in the process. Faced with a similar choice, China would much rather absorb a rich Taiwan — not a destroyed and poor Taiwan — and believes that in time, such an outcome is inevitable. It also wants Taiwanese people to reconcile with Beijing — a hope that the Kremlin has forever destroyed with respect to Ukrainian people. Moreover, the international opprobrium that attaches to Russia because of its war crimes — for example, Vladimir Putin’s indictment by the International Criminal Court — is not something that China wants to attach to its image.

China also deeply values the image of neutral broker — a country that rises above the Russia-US conflict over Ukraine. With Russia on one side and US-led Western countries on the other, it affords China an opportunity to portray itself as a dispassionate and honest mediator in the eyes of the rest of the world. The realism of such peace brokering is irrelevant — the positioning favors Chinese interests.

Given this understanding of Chinese perspectives, how should the West act? It should invite China to June’s UK-hosted Ukraine recovery conference, and make clear that China can be a participant on an equal footing with any other nation in supporting Ukraine’s economic recovery – meaning it will be disqualified if it supports Russia in the war. It should welcome China’s interest in brokering a peace deal while stressing that step one, consistent with China’s call for respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, is the withdrawal of Russian forces from Ukrainian territory.

The West should also discard the misplaced notion that it faces a choice between prioritizing deterrence against China or helping Ukraine defeat Russia. What happens in Ukraine affects China’s global strategy. China is watching Russia’s war against Ukraine — and the West’s support — with the utmost interest.

Thus far, China can observe that Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has failed to achieve its goals, has weakened Russia for a generation, has strengthened Ukraine’s sense of identity, and has woken the West from its habitual slumber. If this is indeed the outcome of Russia’s aggression, something that is still in the balance, China will be more cautious about its approach to territorial expansion in Asia.

By contrast, what if the current situation is reversed? If Russia succeeds in taking Ukrainian territory, maintaining its own regime while forcing change in Kyiv’s government, while the West abandons support for Ukraine after less than two years, the message to the communist government in Being would be to seize Taiwan as quickly as possible. It would signal that despite the short-term costs, the Chinese regime can quite easily overcome any costs in short order. This would be a disastrous signal to send.

The West must therefore recognize that Chinese war aid to Russia is far from a certainty and is indeed something we can influence with our own actions. Quick and decisive aid will do more to deter Chinese aggression in Asia than any renunciation of our friends in Ukraine could ever achieve.

Ambassador Kurt Volker is a Distinguished Fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis. A leading expert in US foreign and national security policy, he served as US Special Representative for Ukraine Negotiations from 2017-2019, and as US Ambassador to NATO from 2008-2009.

Reprinted with the author’s permission from Europe’s Edge, CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. See the original here.

The views expressed in this opinion article are the author’s and not necessarily those of Kyiv Post.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter