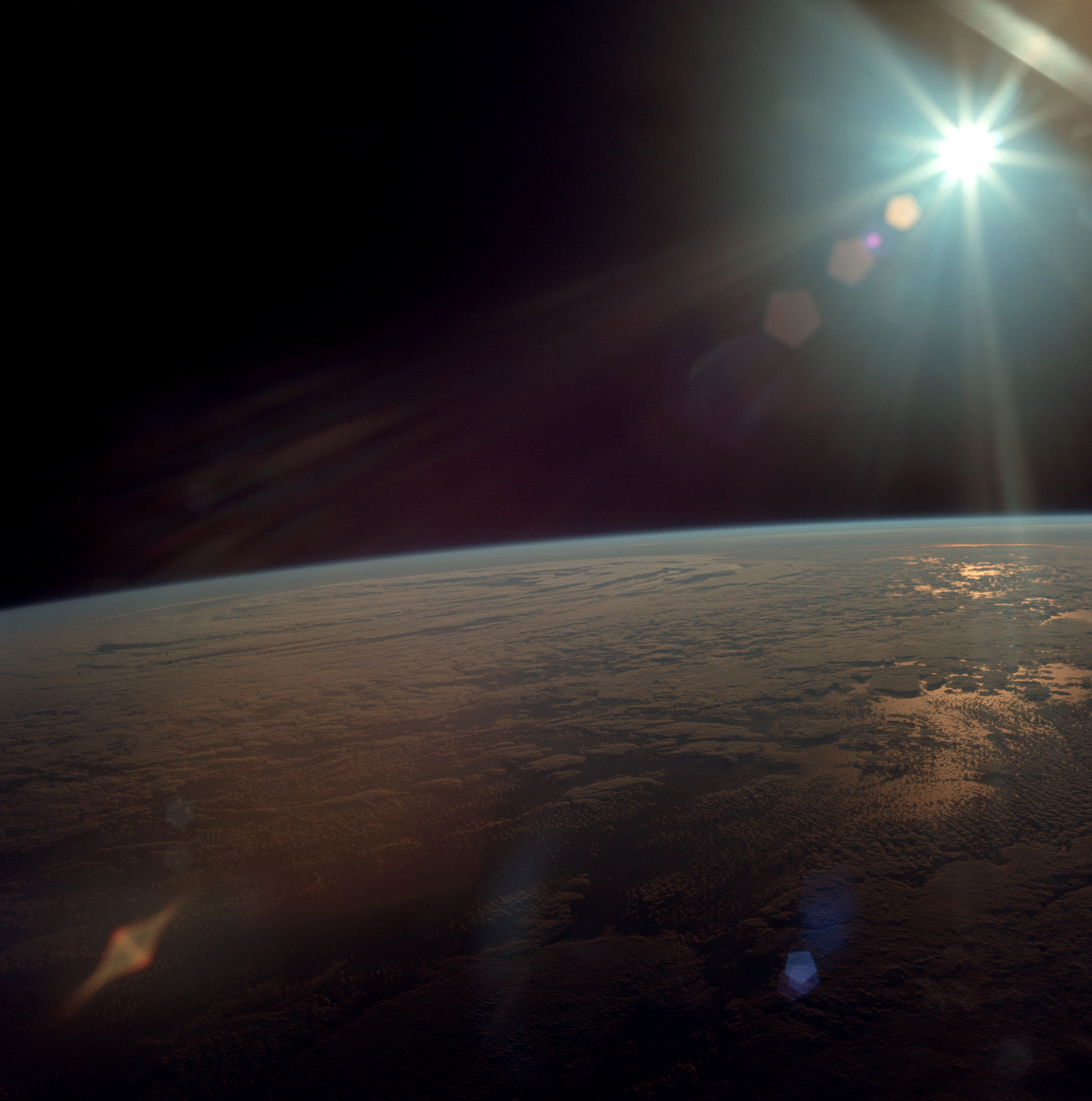

On July 20, 1969, at least 600 million people on all six of Earth’s habitable continents were watching a stunning miracle as it was broadcast live on their black-and-white television screens.

For the first time in history, humans were walking on the Moon.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

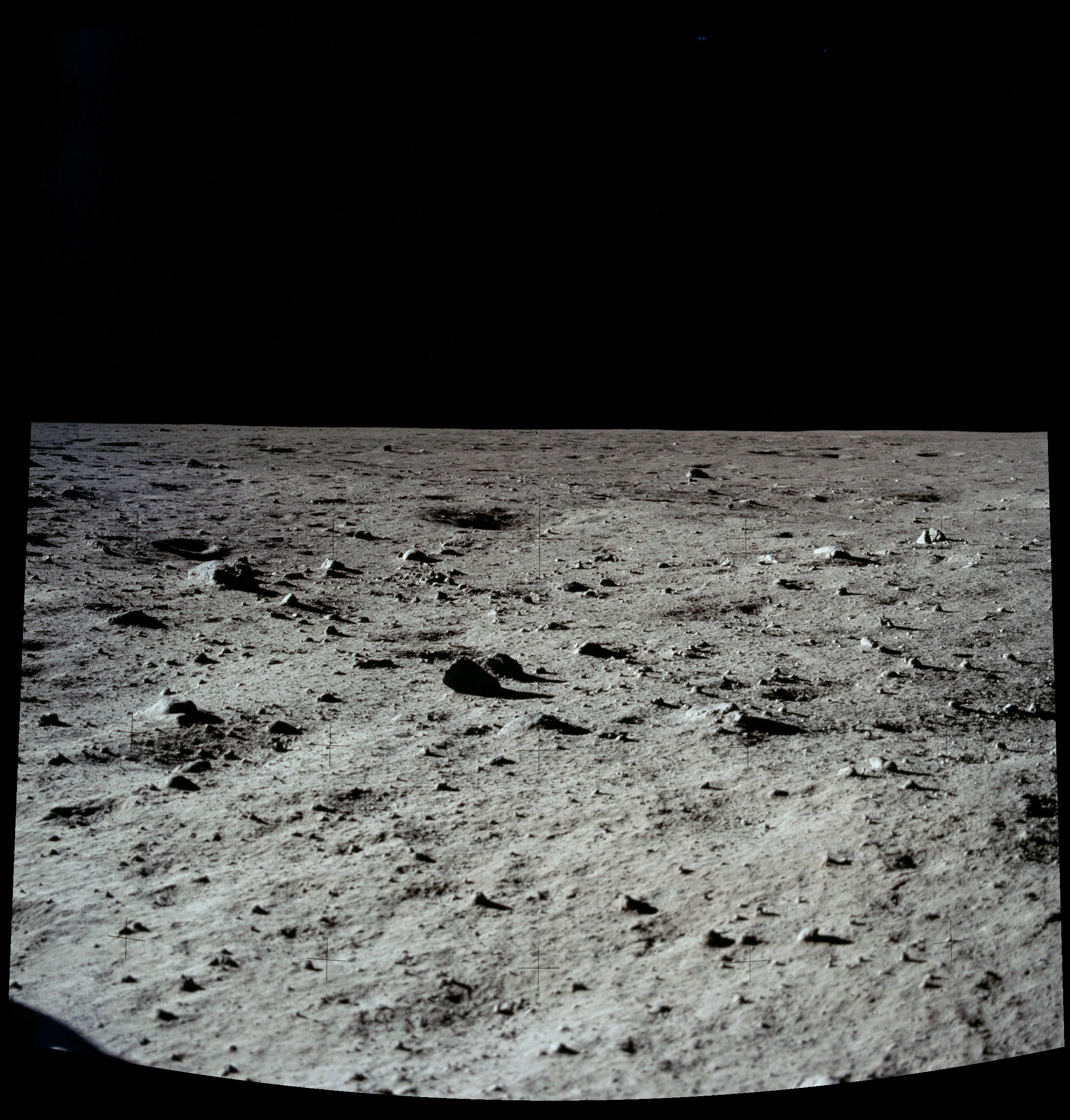

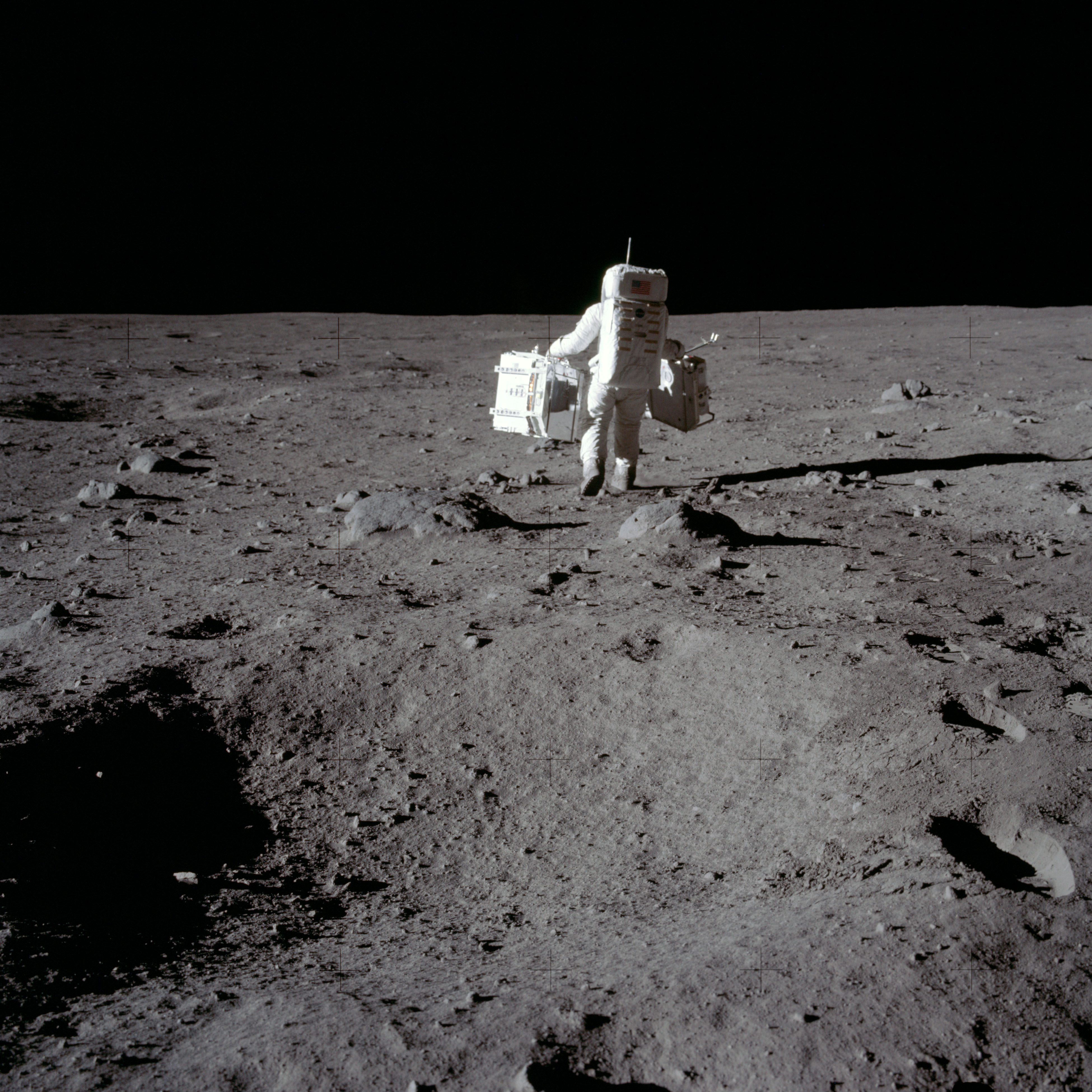

The poor-quality monochrome transmission showed the pale, ghostly figures of astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin awkwardly tramping across the moon dust next to their Eagle lunar module amid total desolation. Occasionally, the buzz of barely distinguishable radio messages between the newly-created Tranquility Base on the Moon and NASA’s mission control center in Houston would break the silence.

“Isn’t that something! Magnificent sight out here,” Armstrong said as he cast his eyes over the flat, gray desert stretching endlessly under pitch-black skies.

“It has a stark beauty all its own… It’s different, but it’s very pretty out here.”

Armstrong had just made his legendary “one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind,” bringing 350,000 years of human curiosity, wanderlust, and passion for discovery to what seemed like a natural culmination.

The greatest voyage of all time was made possible by computers with a processing power that seems laughable today. Still, very little has yet been done since then that can outshine the feat and the decade of unprecedented technological creativity and scientific breakthroughs that brought it about.

Today, exactly 50 years after the Apollo 11 mission, earthlings still can’t forget their finest day, in spite of all the wars and miseries hounding them.

YouTube overflows with videos in all languages, rebutting Moon landing hoax theories. NASA T-shirts are wildly popular. Movies and books on the topic are released every year. And politicians attempt to excite their bored voters with promises to establish manned bases on the Moon within just years.

Humans want to get back to the Moon, and the legendary landing still stands as a sky-sign for enthusiasts like billionaires Jeff Bezos of Amazon and Elon Musk of SpaceX, who dream of seeing fresh human footprints on the Earth’s only natural satellite — or even on planet Mars.

‘Before this decade is out’

When President John F. Kennedy addressed the U.S. Congress on May 25, 1961, announcing the goal of “landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth” — and doing it “before this decade is out” — it seemed an unrealistic enterprise.

The Soviet space program, chaired by ethnic Ukrainian Serhiy Korolyov, was leading the Space Race, having achieved two key milestones: launching the Sputnik-1 satellite in October 1957 and taking Yuriy Gagarin into space in April 1961. American pride had been bitterly stung.

Only an even more stunning achievement could outshine this growing technological and educational gap between the two feuding superpowers of the Cold War. From Kennedy’s perspective, putting an American on the Moon could save the day.

However, things on the ground were far from promising.

At the time of Kennedy’s speech, the United States only had the experience of several successful unmanned suborbital missions. Just one manned suborbital flight took Alan Sheppard into space three weeks after Gagarin as part of the Mercury Project.

But a long list of key proven technologies required to conquer the Moon were missing, things like enduring environmental control and portable life support systems; effective heat shields; technologies for spacecraft rendezvous and docking and extravehicular activities, and a launch vehicle of previously unseen power.

Step by step

After an extremely fierce dispute, NASA eventually settled on the so-called Lunar Orbit Rendezvous mission, for which the agency’s prominent engineer, John C. Houbolt, had advocated.

The complicated plan stated that the Apollo spacecraft would be carried into the Earth’s orbit by an extremely powerful launcher and then boosted further into the vicinity of the Moon.

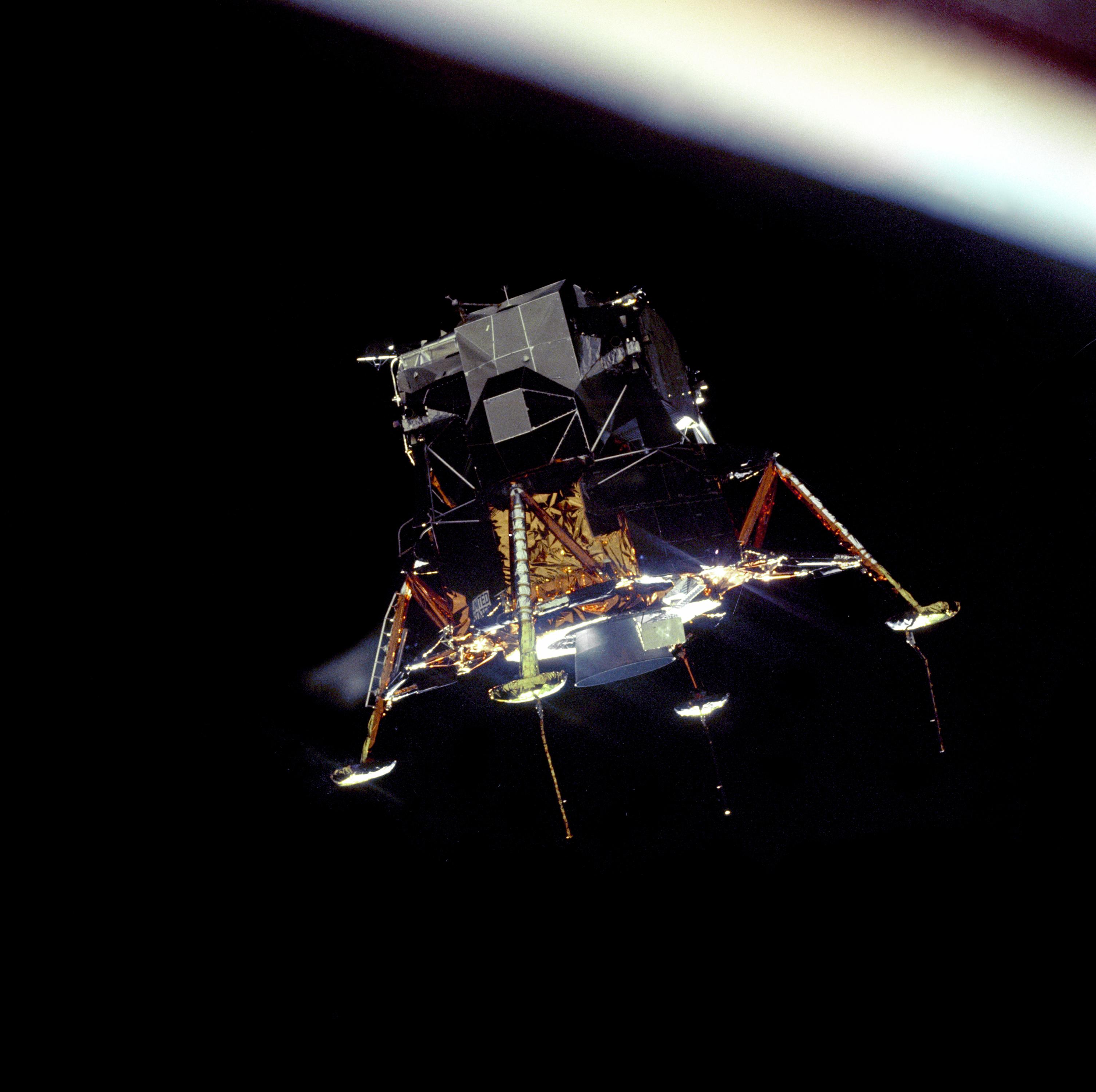

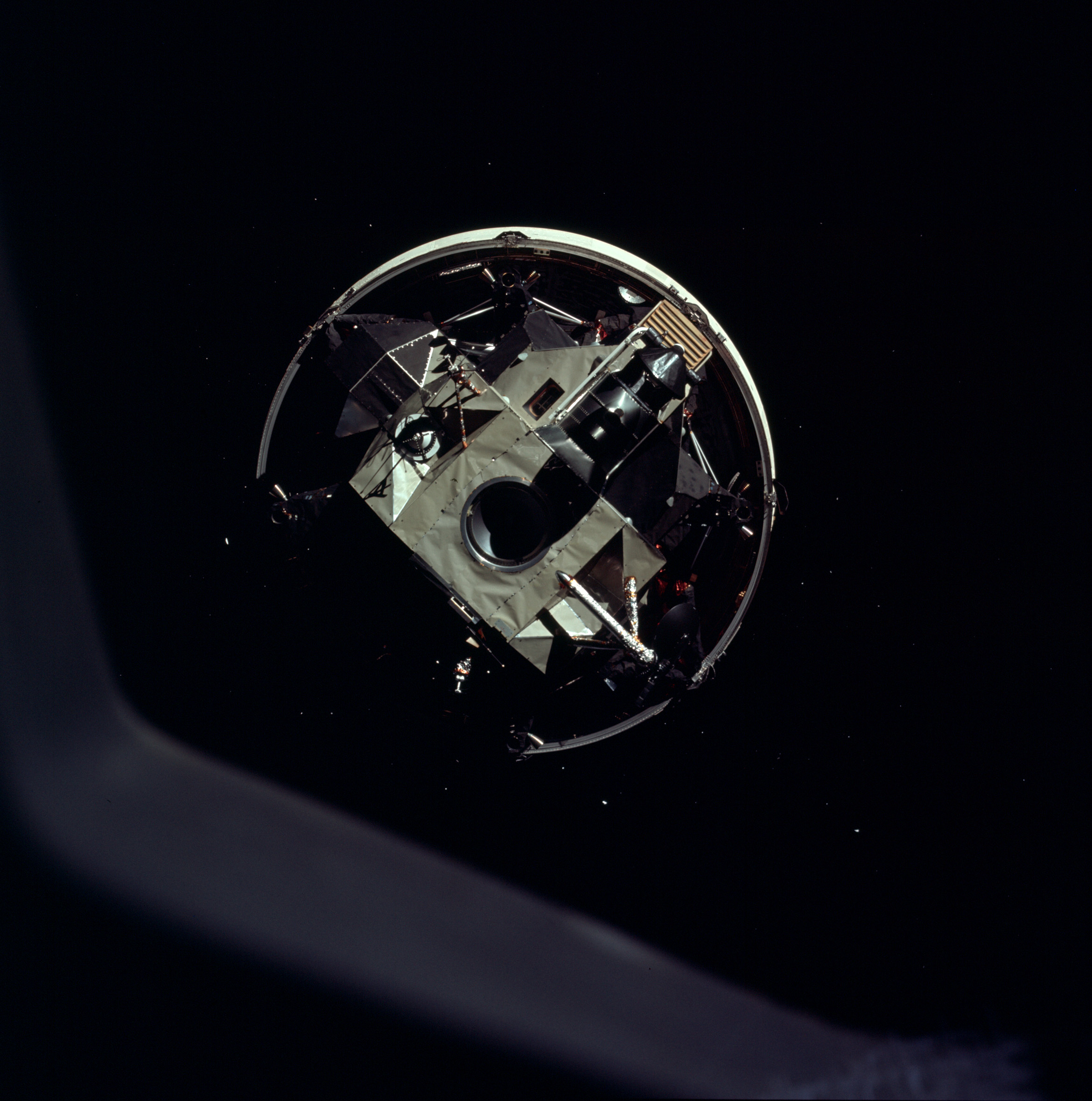

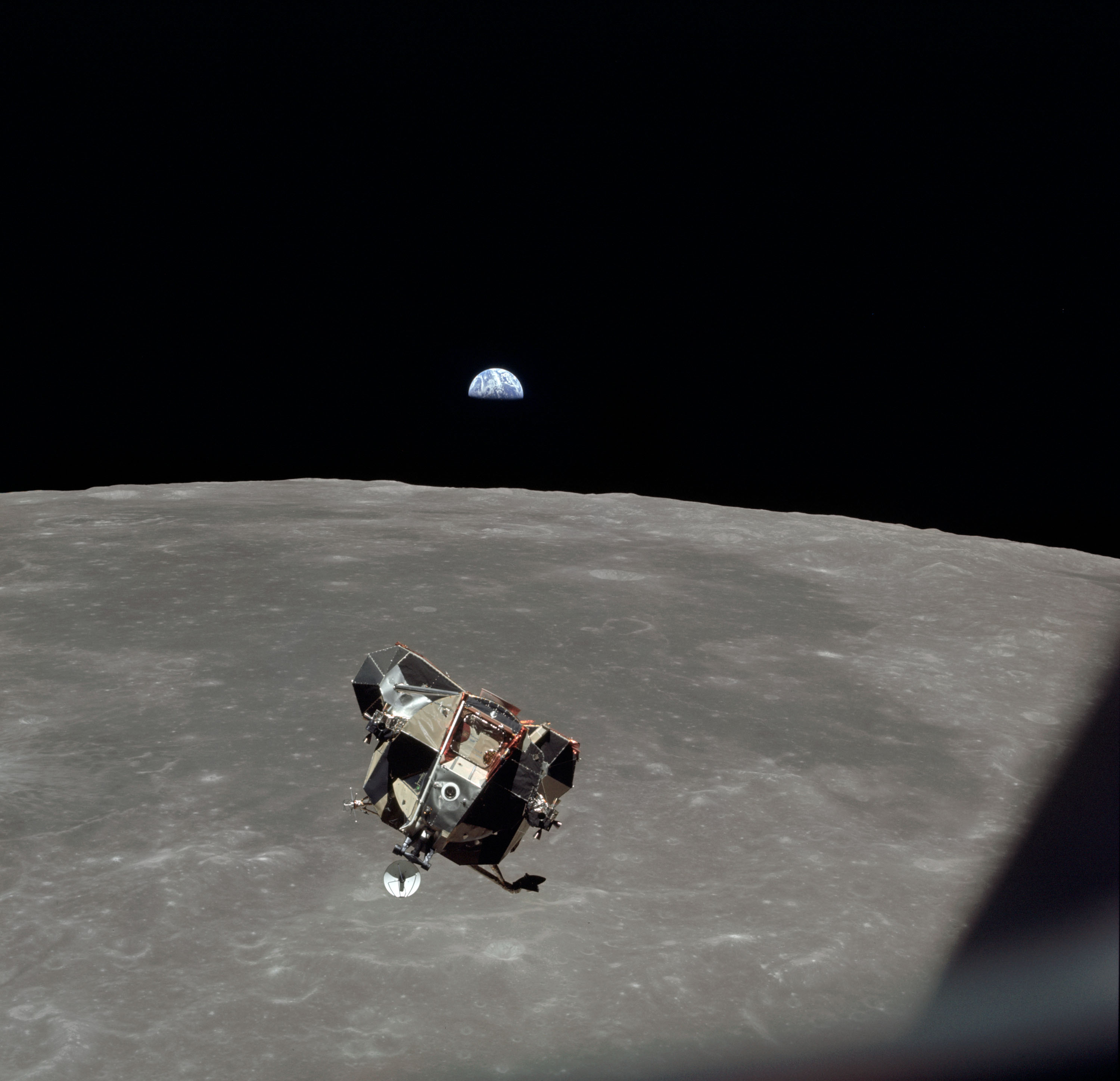

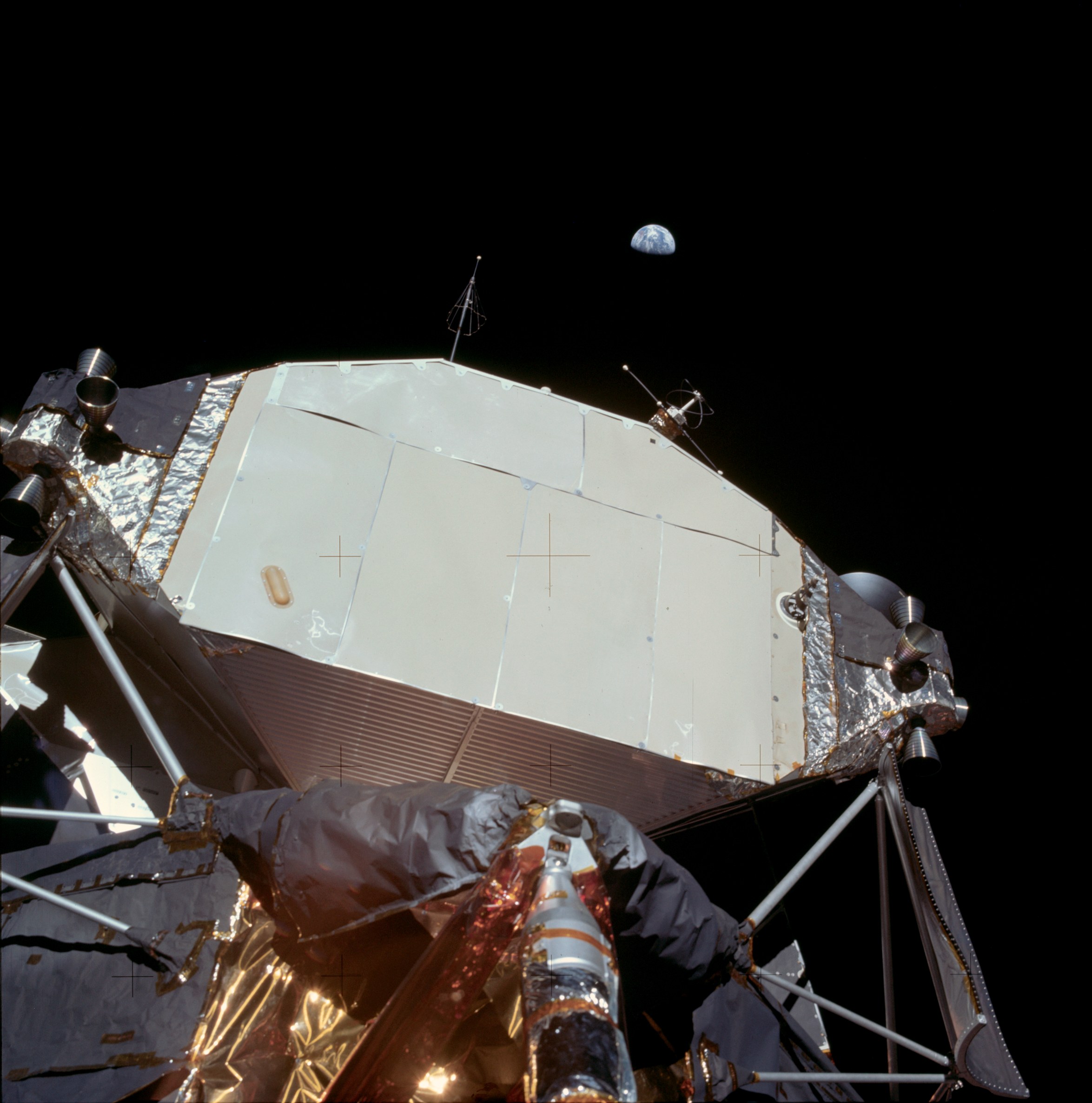

Then, the command and service module would jettison the last rocket stage, dock with the lunar module and enter lunar orbit with it. Next, the lunar module with 2 astronauts aboard would be jettisoned and descended onto the Moon’s surface. After the moonwalk, part of the lunar module would ascend from the Moon’s surface and reattach to the command and service module waiting for it in orbit.

The astronauts would then return to the command and service module and the Apollo would jettison the lunar ascent stage. Finally, the spacecraft would use its engine to boost back to Earth. Only a very small part of the spacecraft, the 3-seat command module cone, would eventually splash down into the ocean and be evacuated.

Some experts believe that, without sticking to this particular mission mode, NASA could have missed Kennedy’s deadline.

All those solutions — and many thousands of others — were developed from scratch and polished off as part of NASA’s space programs Gemini (1961-1966) and Apollo (1961-1972).

Step by step, new test missions were bringing new ingredients to a successful Moon landing and return home.

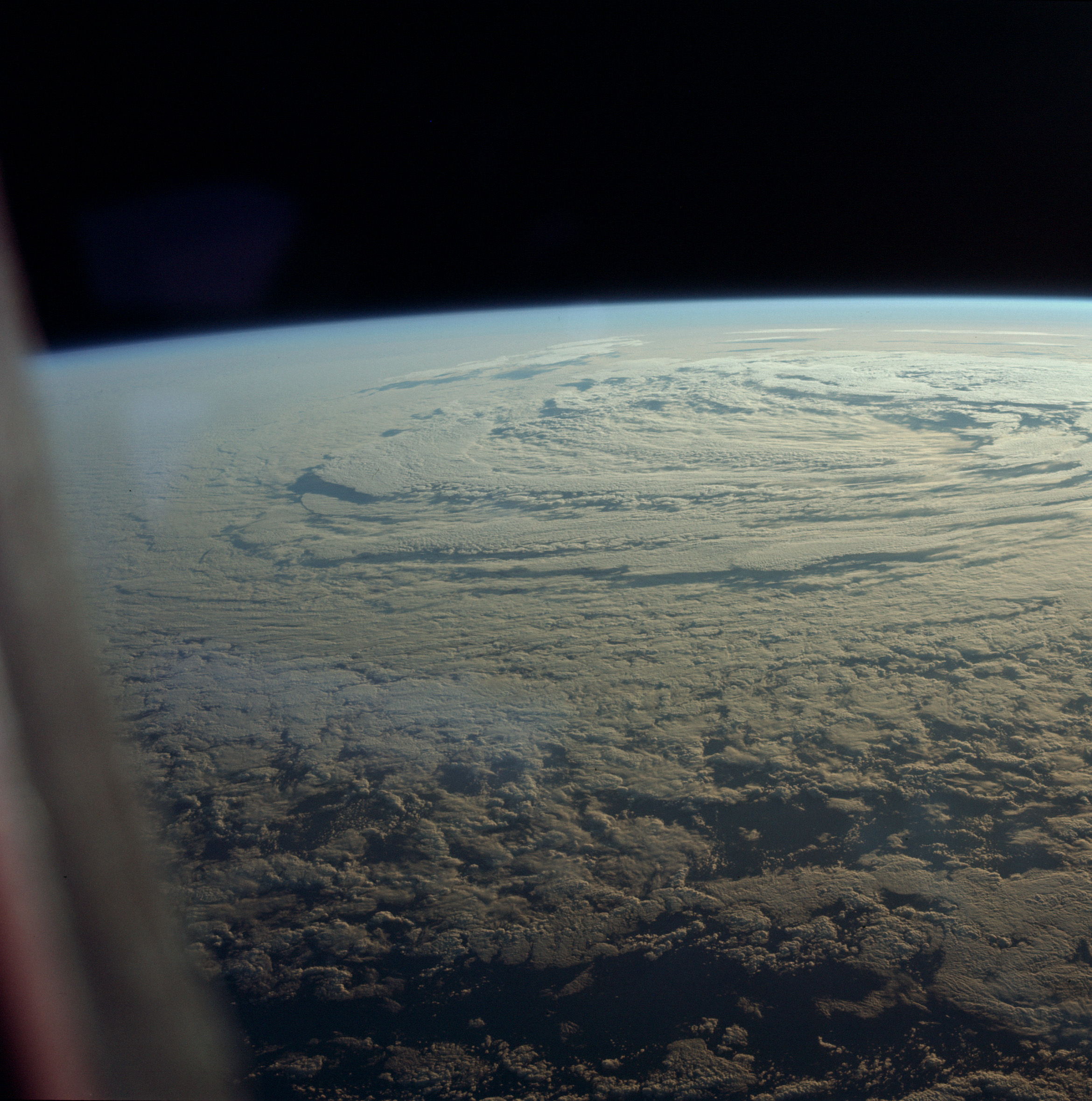

Apollo 4, 5, and 6 all improved upon the technologies used for launches and lunar model design, eventually proving that Saturn V launcher were strong enough and a spacecraft could be safe enough to put a human being on the Moon. When crewed missions began, they developed technology further. Apollo 7 orbited Earth multiple times. Then Apollo 8 left the planet’s vicinity for the first time and made 10 orbits around the moon in December 1968.

Apollo 10 was a dress rehearsal for a lunar landing. It entered the Moon’s orbit in May 1969 with a fully functional command-and-service module designed by the North American Aviation company, and turned back home only 15 kilometers away from the lunar surface.

Kennedy’s dream indeed launched history’s greatest peacetime technological and resource effort. The Apollo program alone cost nearly $25 billion ($153 billion in 2018 prices). At its peak, it employed nearly 400,000 engineers, scientists and technicians, and 20,000 companies and universities worked for NASA.

“In peace for all mankind”

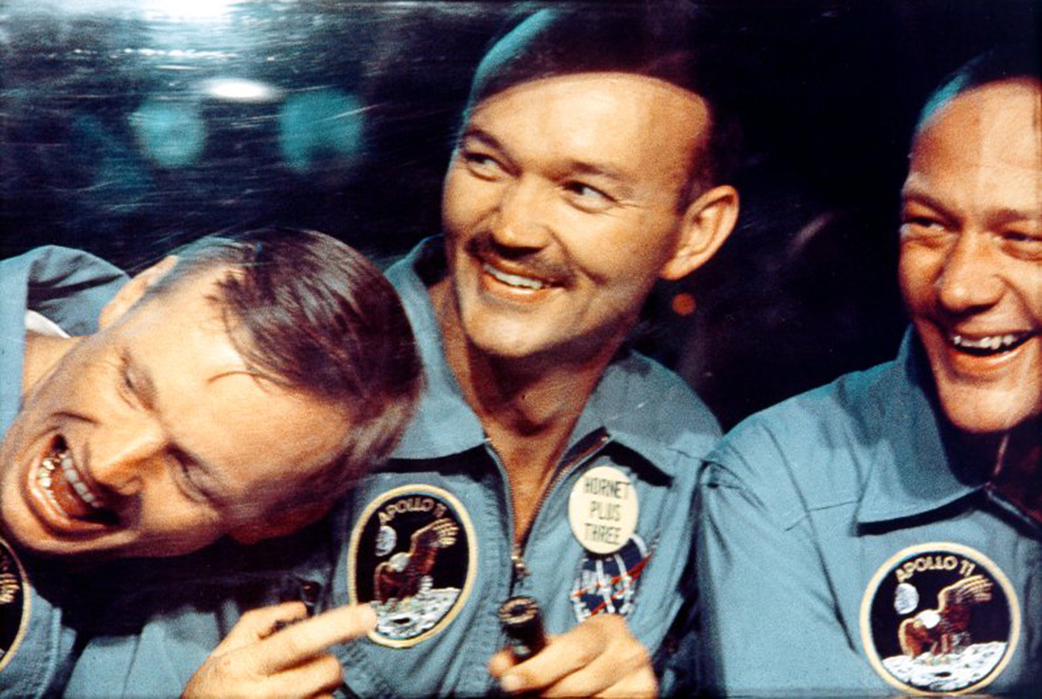

And then the long-awaited day came. On July 16, the Apollo 11 crew of commander Neil Armstrong, lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin, and command and service module pilot Michael Collins started their odyssey from Cape Canaveral after a strict training and a lengthy quarantine.

The Apollo 11 launch was in the global spotlight. Nearly 3,500 reporters covered the event from the scene, and the live TV broadcast was transmitted to 33 countries.

Up to an estimated 1 million people converged near the Kennedy Space Center to see the launch with their own eyes, creating immense traffic jams in the country. They filled every hotel room within a 100-kilometer range. Others paid to sleep in motel yards, asked locals for lodgings, or simply stayed on overcrowded beaches nearby. Local souvenir sellers and caterers enjoyed astronomical profits.

The Kremlin initially reacted coldly — the Soviet envoy to the United States first accepted and then declined his invitation to the launch. But a squadron of eight Soviet warships observed the launch from 46 kilometers southeast of Miami.

As Baltimore Sun reporters in Moscow wrote on the eve of the launch, “only the sharpest observer of the Soviet new media could guess, as he went to bed tonight, that Americans will try to send men to the Moon tomorrow.”

The flight was conducted almost flawlessly at all stages — and 102 hours and 45 minutes after the launch, Armstrong finally reported: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

The NASA mission control center, as well as half of the world, exhaled perhaps the greatest sigh of relief in human history. A decade of blood, sweat, and tears had allowed humans to touch a celestial body beyond Earth for the first time in history.

The Cold War was still at its peak between the two superpowers — but not between the space explorers on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

“When Armstrong stepped on the lunar surface and everyone in the U.S. was applauding, we, the Soviet cosmonauts, were holding our fingers crossed,” Alexey Leonov, the first human to spacewalk in 1965, later recalled. “We were sincerely wishing these guys success.”

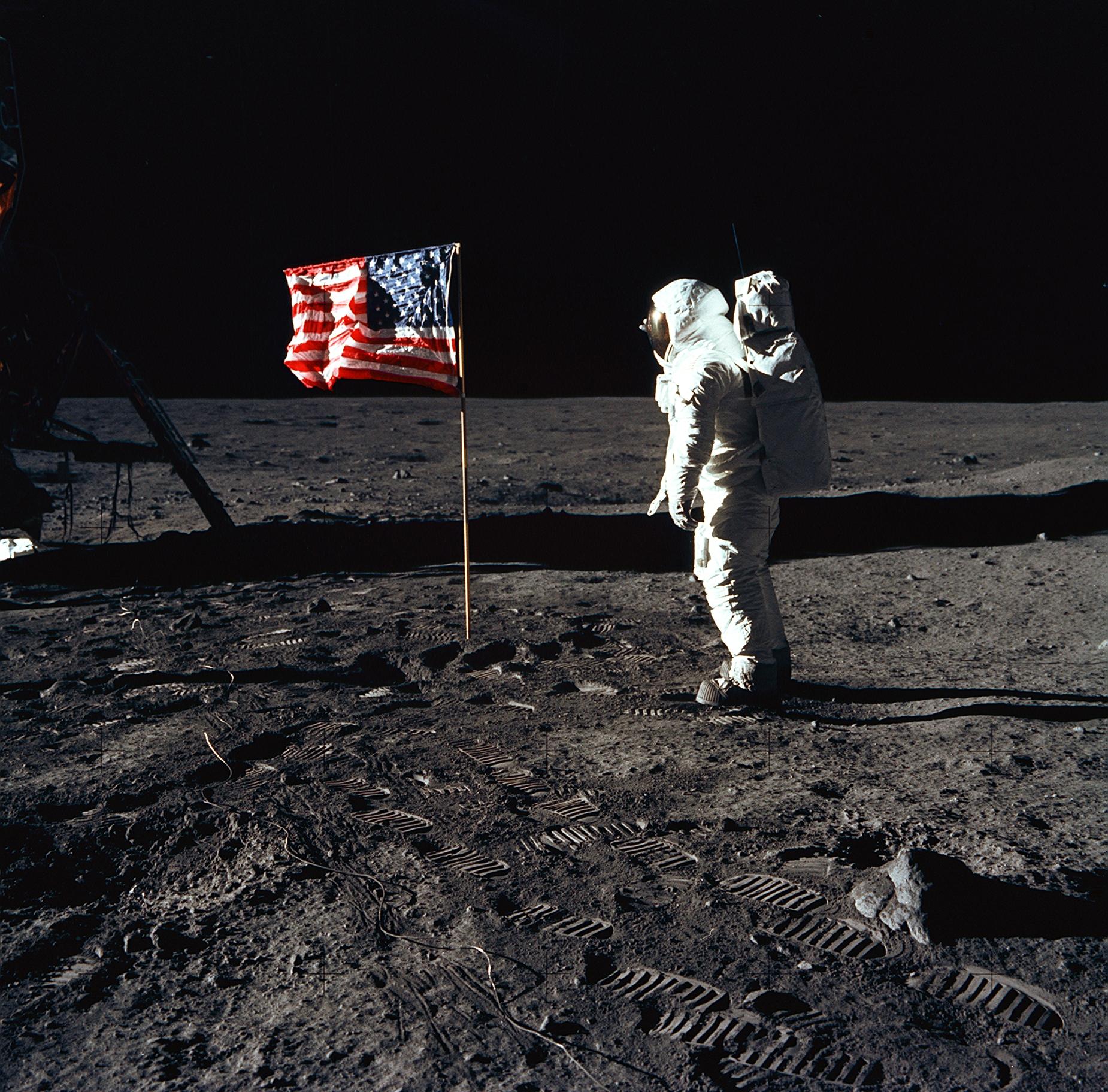

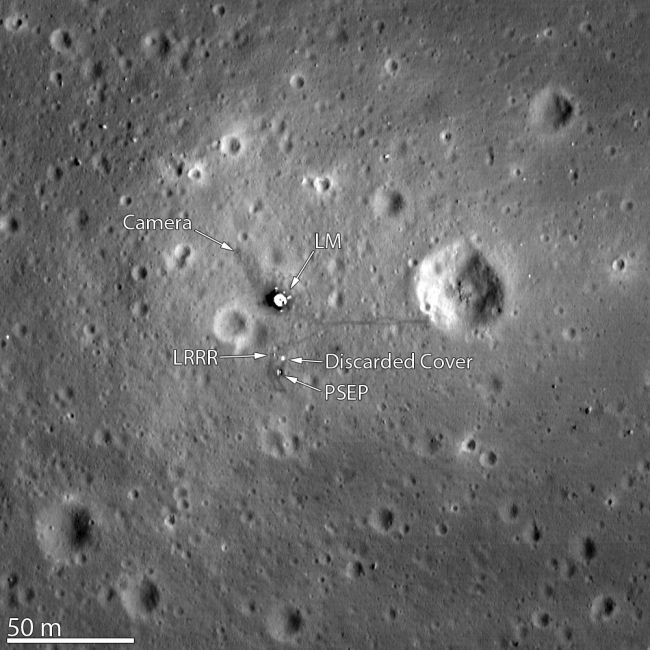

Aldrin and Armstrong spent 21.5 hours on the Moon, including 2.5 hours of extravehicular activity. They collected 21.5 kilograms of lunar soil for research and installed the first scientific instruments on the Moon.

Among many things that the astronauts brought with them to the Moon were small flags of the 135 member states of the United Nations. It was a sign of the mission’s peaceful aim for all of humankind. They also had memorial medals of killed Soviet cosmonauts Yuriy Gagarin and Vladimir Komarov — who had been killed in 1968 and 1967, respective — and of American astronauts Virgil Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee. The latter three had died in a fire during the Apollo 1 mission tests in January 1967.

Their memorials were left behind on the Moon forever.

As planned, the Eagle ascended back into the lunar orbit and connected with the Columbia command module piloted by Collins. Then, the astronauts splashed into the Pacific Ocean on July 24, to be recovered by the USS Hornet with U.S. President Richard M. Nixon onboard.

Only after the astronaut’s safe return did the Soviet media start covering the Apollo flight and the Kremlin officially congratulated the United States.

Meanwhile, the astronauts faced 21 days of strict quarantine, which discovered no alien bacteria brought back from space. Then, they went on a triumphant world tour to 22 countries, with millions of people cheering on the first men on the Moon.

It took 2,982 days for NASA to accomplish Kennedy’s mission. But Kennedy did not live to see it. He was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963.

Human instinct

The Apollo program continued through December 1972, putting 10 more humans on the Moon in five subsequent successful missions. In 1970, Apollo 13 proved a major failure, but the astronauts managed to return safely to Earth in their heavily damaged spacecraft.

Besides achieving political and scientific goals, the Moon missions also led to over 1,600 inventions registered by NASA. Most importantly, it significantly helped with the development of integrated microcircuits — still a crucial aspect of modern technology in any industry.

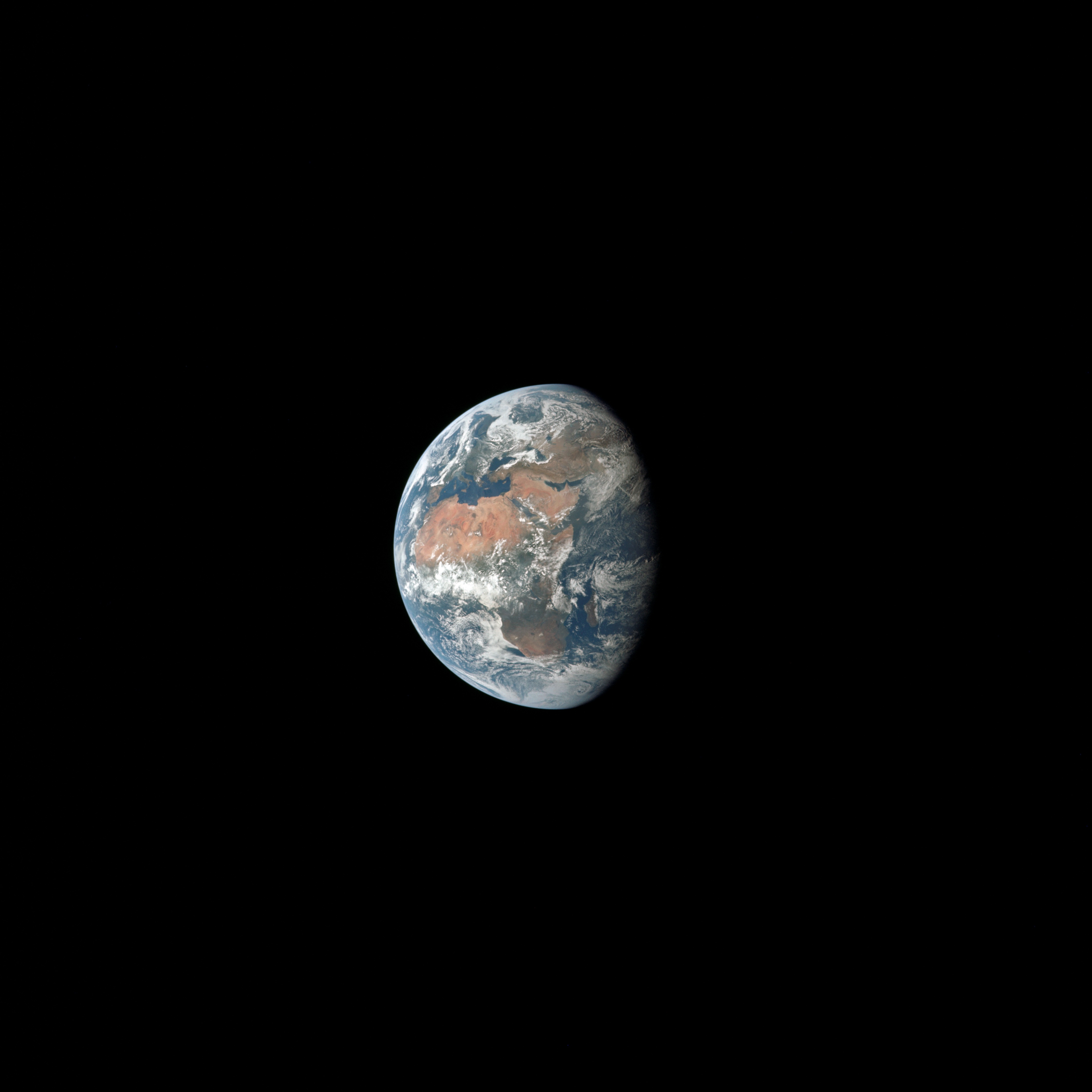

The last mission, Apollo 17, brought home the iconic “Blue Marble” photograph of Earth, which helped trigger a global surge in environmental movements seeking to protect our beautiful and fragile planet.

“We went to explore the Moon, and in fact discovered the Earth,” Eugene Cernan, the last man to walk on the moon, recalled in 1972.

Half a century later, the 1969 landing remains history’s greatest technological achievement. Now, only setting foot on Mars can outshine it, says Pavlo Degtyarenko, chairman of the State Space Agency of Ukraine.

“We had no clue what a long technological leap mankind had made then,” he says.

“This is proven by the fact that 50 years have passed, and only now are we seeing a new wave of interest in exploring the Moon and planets. Because, at that moment, the technological solutions achieved were astronomically expensive, (and they seemed) beyond humankind’s reach. For this reason alone, this anniversary should be celebrated.”

Immense resources were allocated to the Space Race for political reasons. But such a peaceful scientific competition was much better than a “rivalry of big nuclear sticks,” Degtyarenko says.

The scientist has no doubts that the Apollo program, despite its colossal expense, contributed to the greater good of mankind.

“It’s the same as when Christopher Columbus or Amerigo Vespucci or Vasco da Gama were reaching out to their kings to ask for money for their expeditions,” he says.

“Without dreaming, without taking steps beyond what is known, humanity leans toward degradation. Humankind can survive and exist only through development. Thus, such a step was necessary.”

Meanwhile, Moon exploration continues — even without boots on the ground. Just recently, in early 2019, the Chinese probe Chang’e 4 reached the far side of the Moon for the first time in 60 years. The Israeli probe Beresheet, bearing the slogan “Small country, big dreams,” almost made it in April, but ultimately crashed on the Moon’s surface.

In mid-May, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos presented a manned lander project called Blue Moon that could be launched by 2024.

“We will go back to the moon, this time to stay,” the billionaire enthusiast said during a press conference in Washington.

Ukraine’s main space director has no doubts that astronauts will indeed soon return to the Moon — because this is a vital part of human nature.

“(Exploring) is an integral human instinct,” Degtyarenko says.

“A child, having barely learned to crawl, creeps beyond the room’s door. Then it walks out of the house. Then it leaves the city. Then it goes to a forest or a sea. Then it goes to another continent and so forth. Humankind has always had the goal of going further. It’s a pure instinct — not of any single person, but of humankind as a species.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter