Ukraine’s richest man has lost more than half of his net worth since the EuroMaidan Revolution nearly three years ago, but he’s been able to straddle extreme political divides: keeping his influence in Ukraine, his businesses in Russian-occupied Donbas and his working relationships with both Russia and the West.

Editor’s Note: The following article is part of the Ukraine Oligarch Watch series of reports supported by Objective Investigative Reporting Program, a MYMEDIA project funded by the Danish government. All articles in this series can be republished freely with credit to their source. Content is independent of the donor.

Story At A Glance

- Rinat Akhmetov has long been Ukraine’s richest oligarch, even after his wealth plunged in recent years and his longtime ally, Viktor Yanukovych, fled power in 2014

- He is reclusive and rarely grants interviews. Sightings of him in Ukraine have been few and far between since Russia’s war began in 2014

- Akhmetov straddles all political divides – keeping working relationships with the West, Kyiv, Moscow and Russian-occupied Donbas. His spokespeople deny accusations that he stoked the Kremlin-backed separatist war in the east. He considers himself a Ukrainian patriot.

- Even though he has had trouble getting a visa to America, Akhmetov has been welcomed for talks at the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine to help resolve Russia’s war against Ukraine

- He gained much of his wealth during an era of crony capitalism, rent seeking and rigged privatizations. He owns some of the most expensive real estate in London, buying a luxury building at One Hyde Park for more than $210 million in 2011

Rinat Akhmetov

Date of birth: Sep. 21, 1966.

Place of birth: Donetsk

Wealth: $2.9 billion according to the current Forbes ranking, the richest Ukrainian for many years.

Key Assets: System Capital Management, which incorporates more than 100 mining, metal, energy, finance, media and other companies; Metinvest mining and steel company; DTEK energy company; Ukrtelecom, the country’s fixed-line telephone monopoly; the First Ukrainian International Bank; Media Group Ukraine, which includes Ukraina TV channel, Segodnya national newspaper and some regional media outlets.

Personal: Married to Lilia Akhmetova (Smirnova); two sons, Damir and Almir.

Praised for: Since the beginning of the war, his charity foundation delivered more than 10 million food packages to people in the Donbas. His foundation has also supported tuberculosis and

cancer treatment programs and media development projects.

Criticized for: Amassing wealth thanks to long-time ties with Ukraine’s top officials, including ousted President Viktor Yanukovych; alleged links to separatist forces in Donbas, accusations that he denies.

STORY STARTS HERE:

His close ally, President Viktor Yanukovych, fled power nearly two years ago.

He’s lost most of his fortune since then.

But, all things considered, Rinat Akhmetov is doing more than fine.

He remains Ukraine’s richest man, even though his estimated net worth wealth has tumbled from $11.2 billion in 2014 to $2.9 billion now, according to Forbes.

While he has had trouble getting a U.S. visa, he meets with officials in the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine and other diplomats to discuss the Minsk peace process, elections in Russian-controlled Donbas and humanitarian aid in eastern Ukraine.

Unlike other allies of Yanukovych, Akhmetov has also managed to escape economic sanctions and arrest, but not criminal investigations.

While he left the Donbas, he is free to stay in Ukraine despite accusations – denied by his representatives – that he had links to separatists, if not a role in stoking the conflict that blossomed into a war killing 10,000 people.

In fact, Akhmetov continues to perform the amazing feat of having working relationships with Ukraine, the West, Russia and finally, in the Kremlin-controlled separatist zones, where he operates much of his businesses.

How does he do it?

He won’t say. The reclusive billionaire – who is known to be litigious if he thinks he’s been libeled – refused to be interviewed for this story, while his spokespeople only responded to written questions.

Dominating force

Money buys power and, since he has more of it than anybody else in the nation, Akhmetov is a force to be reckoned with like no other. The nation’s gross domestic product is only $100 billion, and its national budget is $30 billion yearly – less than half the size of the one in Poland, which has 7 million fewer people.

Akhmetov also has large media holdings, including daily newspaper Segodnya and Ukraina TV, with which to wield his power. But whether he is capable or interested in using this influence to bring peace between Ukraine and Russia remains to be seen.

Akhmetov, who was the most influential person in the Donbas before fleeing in 2014, has held on to much of his business empire there, even after Russian troops and local militants took over.

On Feb. 16, Akhmetov appeared to play a significant role in keeping ex-Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk in his job, when at least five lawmakers from the Opposition Bloc that pundits say are loyal to him refused to support a vote of no-confidence in the government at the last moment. Eventually Yatsenyuk was voted out of power and lost his job on April 14 to presidential loyalist Volodymyr Groysman, who was speaker of the Verkhovna Rada.

From coal mines

Born in Donetsk in the family of a coal miner, Akhmetov, 50, amassed his fortune during the wild 1990s into the early 2000s, when non-transparent and uncompetitive privatizations of state-owned assets were the norm after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union.

Today his empire controls more than half of Ukraine’s steel, mining and thermoelectricity production.

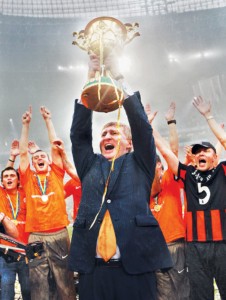

He has also had a longtime interest in sports, taking over as president of the Donetsk Shakhtar soccer team following the October 1995 explosion that killed his former mentor, Akhat Bragin. The crime remains unsolved.

The fastest estimated growth in his net worth, in 2010, coincided with the election of his long-time friend Yanukovych as Ukraine’s president. That year Akhmetov’s wealth more than tripled – to $16 billion, from $5.2 billion, according to Forbes.

When Yanukovych’s regime collapsed on Feb. 22, 2014, following the EuroMaidan Revolution, Akhmetov lost his most powerful base of influence, the Yanukovych-led Party of Regions. But he survives, mostly unscathed.

Whose side is he on?

But Akhmetov’s reputation took a hit during and after the EuroMaidan Revolution among people who saw him as playing both sides.

As a Yanukovych ally, he became a target for demonstrators, some of whom protested outside his One Hyde Park luxury home – which he bought for more than $150 million in 2011 – in London.

On Dec. 31, 2013, Akhmetov – without his ever-present security entourage – got out of his car and approached EuroMaidan activists who were picketing his residence in Donetsk.

“If you want Ukraine to be strong, I’m with you,” he told them.

But by the following spring, with Yanukovych no longer in power, he turned his attention to Kremlin-backed separatists.

A YouTube video shows that, when Russian-backed protesters captured the building of Donetsk Oblast’s administration, Akhmetov approached them late on April 8, 2014 and pledged to prevent law enforcement agencies from storming the building.

“If there is a crackdown, I will go together with you there,” he said in trying to win over the hearts of hundreds of protesters who were calling for Russia to annex the Donbas, as it did with Crimea weeks earlier.

But he also took a pro-Ukrainian line, stressing that the region’s future was best under Ukraine. “For me, Donetsk, Donbas, Ukraine are in my heart forever,” he said at the meeting with Yatsenyuk on April 11, 2014.

Yatsenyuk promised to keep the law granting special status for the Russian language, and Akhmetov argued that Donbas should remain Ukrainian.

But on the very next day, retired Russian intelligence officer Igor Strelkov captured police offices in the cities of Sloviansk and Kramatorsk in Donetsk Oblast, sparking the military conflict that continues to this day.

Taras Chornovil, a former member of Yanukovych’s party who claims to have been acquainted with Akhmetov, said the billionaire appears to have initially – before Russia took full control in the Donbas through direct military intervention and proxies – tried utilizing separatist sentiment in the region to gain leverage with the new authorities in Kyiv.

“Apparently (Akhmetov) wanted to lead the local forces to bargain with the authorities in Kyiv… He believed he could keep it all under control, but a Russian scenario was launched instead,” Chornovil said. “He was shown who is the boss in the region… So he decided to play for neither of the sides.”

It took Akhmetov until May 20, 2014 to speak out against the separatists and accuse them of “genocide against Donbas.”

But the statement didn’t erase the opinion of some people that he had a role in the stoking the conflict.

In early March 2014, shortly after Yanukovych fled power, then-Donetsk Oblast Governor Andriy Shyshatsky met with regional mayors and advised them to create “self-defense units” out of local hunters and veterans of the Afghanistan War to fight Ukrainian nationalists, said Denis Kazansky, a popular pro-Ukrainian political blogger from Donetsk.

“Shyshatsky is an Akhmetov protégé,” Kazansky said, adding that Shyshatsky had served as head of Khartsyzsk pipe plant, which is owned by Akhmetov. “None of it could have happened without Akhmetov’s knowledge.”

Akhmetov’s spokesperson did not respond to these claims.

Ruling by proxy

On May 25, 2014, a group of outraged Russian-backed separatists marched to seize Akhmetov’s residence in Donetsk. But separatist leader Oleksandr Zakharchenko and militants of his Oplot group prevented the seizure, according to Kazansky, who witnessed the incident.

A YouTube video shows another pro-Russian militant leader, Muscovite Alexander Borodai, telling the crowd that Zakharchenko will take custody of the house as long as they negotiate with Akhmetov.

As of June 2016, Akhmetov’s residence still remains intact and is maintained by employees, several independent sources in Donetsk told the Kyiv Post.

According to an investigation published by the Insider news site in 2014, Zakharchenko used to work for companies linked to former lawmaker Serhiy Kiy, a longtime associate of Akhmetov.

Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta wrote, quoting a Kremlin source, that Akhmetov had lobbied for the nomination of Zakharchenko as head of the Donetsk separatists when speaking with Vladislav Surkov, an influential aide of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

“A source close to the Novorossiya project claims that the richest Ukrainian oligarch Rinat Akhmetov asked Vladislav Surkov for (the nomination of) Zakharchenko,” the newspaper wrote in December 2014.

Akhmetov’s spokesperson did not respond to questions about the oligarch’s alleged relations with Zakharchenko and alleged meetings with Surkov. Zakharchenko’s spokeswoman told the Kyiv Post by phone she had no information about his relations to Akhmetov or Kiy.

Militants of the separatist Vostok Battalion have been seen defending the Donbas Arena soccer stadium, which is controlled by Akhmetov, and his other businesses. Chornovil said Vostok, at Akhmetov’s request, had also helped to release journalists and activists taken prisoner by Russian-backed militants in Donetsk.

Vostok’s former commander, Aleksandr Khodakovsky said sarcastically and evasively in an interview with Forbes in 2015: “If I’m Akhmetov’s man, then he is the biggest patriot of the Donetsk People’s Republic, because in such a situation, he is financing the unit which allows the republic to exist.”

He added: “I am not Akhmetov’s man directly, but because my position lies in preserving his business, it’s to the benefit of Akhmetov … playing into his hands.”

Akhmetov’s spokeswoman said that Akhmetov had never financed any separatist groups.

On Feb. 20, activists of the OUN nationalist group, whose members were defending Ukraine in the Donbas war as a volunteer battalion, smashed the windows of Akhmetov’s company in Kyiv, blaming the oligarch for provoking the military conflict.

“We promised not to let him alone,” OUN leader Mykola Kokhanivsky told the crowd before rushing to Akhmetov’s office. “It was him in particular who caused this war, in which Ukrainian blood is still being spilled.”

Separatist leaders have said since 2014 that they have not nationalized Akhmetov’s businesses in regions under their control as they need to keep the local population employed and to pay salaries. But on June 1, Zakharchenko banned Akhmetov along with some other former Yanukovych allies from entering the separatist-controlled areas.

A split empire

The tycoon’s alleged dealings with Russian-separatist forces are linked to the state of his assets in eastern Ukraine.

Since the beginning of Russia’s war in 2014, Akhmetov’s businesses have been split between Ukrainian-controlled and separatist-held areas, with Systems Capital Management companies having to transport their products across the war’s frontlines.

The hardest time for Akhmetov’s business was in August-October 2014, when some steel plants stopped working because of heavy fighting, analysts say. But the output of most businesses improved in 2016.

According to estimations of Concorde Capital investment bank, in September the Akhmetov-owned Yenakiyeve Steel Mill was making 71 percent of its pre-war output, which is 3 percent better than in September 2015.

Akhmetov’s Komsomolets Donbasa coal mine had an output at 72-percent of its pre-war level in September, 12 percent better than a year ago.

Although Akhmetov’s companies deny it, analysts don’t see how he can keep doing business in Russian-occupied Donbas without making payments to the separatist leadership.

“As rational people, we understand that it’s impossible to transport coal from Luhansk Oblast without getting approval from those who control it,” Oleksandr Parashchiy, head of research at Concorde Capital, told the Kyiv Post.

“As rational people, we understand that it’s impossible to transport coal from Luhansk Oblast without getting approval from those who control it,” Oleksandr Parashchiy, head of research at Concorde Capital, told the Kyiv Post.

On the other hand, separatists are not preventing Akhmetov’s companies from paying taxes to the Ukrainian budget and are allowing them to operate.

Parashchiy attributed this to the separatists’ understanding that they needed SCM companies because they provide employment and contribute to social stability in an economically depressed region.

Akhmetov’s businesses could cease to function if Kremlin-backed separatists seized these companies or forced them to quit Ukrainian jurisdiction.

“They can’t afford working under norms that contradict international law,” Parashchiy said. “What sane country would accept products that were produced (in the occupied territories)?”

Akhmetov’s aid

Russian-backed separatists have repeatedly prevented Ukraine’s government from directly providing humanitarian aid to the civilian population of the war-torn Donbas region under their control, but have curiously allowed Akhmetov’s aid to flow in and be freely disbursed. Supplies of humanitarian aid to the region also enable Akhmetov to retain support among the region’s population.

Since the war started, his charity has delivered more than 10 million food packages to people in the Donbas.

In a survey by the International Republican Institute released in January, Akhmetov was number one in popularity in Ukraine-controlled Donbas, with 35 percent support – far ahead of other politicians or business people.

Doing business in Russia

As Russia’s war in the Donbas cut off railways and other logistical routes that were vital to supplying Ukraine’s electricity generators with fuel, Akhmetov’s companies somehow managed to keep coal supplies flowing amid peak battles.

Coal was shipped into Ukraine from mines also owned by the oligarch in Russia’s Rostov Oblast. Coal was also temporarily shipped by rail out of Ukraine’s war-torn regions through Russian territory and back into Ukraine. Russia allowed it.

“It was leaving Ukraine, passing over a small part of Russian territory and then entering Ukraine,” Anton Kovalyshyn, a press secretary with Akhmetov’s DTEK energy company, told the Kyiv Post.

In late 2014, however, Russian railway officials stopped the shipment of coal to Ukraine. They didn’t explain the reasons.

With Ukraine and West

On Jan. 22, 2015 Akhmetov was interrogated for several hours at the Prosecutor General’s Office as part of a criminal case into the financing of separatists. Through a spokesperson, Akhmetov has denied the claims.

The Prosecutor General’s Office told the Kyiv Post that it was still investigating the case, but no notice of suspicion had been filed. Last year, then-Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin said that “there are no grounds for arresting Akhmetov for the time being.”

Sergii Leshchenko, a lawmaker of the Petro Poroshenko Bloc, wrote in a blog for Novoye Vremya magazine that Yatsenyuk had regular meetings with Akhmetov and had defended the oligarch’s business interests over the two last years. “Today Akhmetov is the strongest backstage ally of Yatsenyuk,” Leshchenko wrote.

Yatsenyuk has denied this widely held view.

This opinion is shared by Yegor Firsov, a former lawmaker who was ejected from parliament after quitting the faction of President Petro Poroshenko. Firsov, who used to work as journalist in Donetsk and was called as a witness in Akhmetov’s investigation, said Akhmetov is escaping justice thanks to his control of a handful of lawmakers in parliament and friendship with top officials.

“It’s no secret that Akhmetov is on good terms with (former) Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk,” Firsov added.

Volodymyr Fesenko, head of the Penta political research think tank, attributed the lack of progress in investigations against Akhmetov to an informal agreement among the Ukrainian elite that political foes would not jail each other.

Vitaly Bala, an analyst at the Situations Modeling Agency, also believes there could be agreements between Akhmetov and the Poroshenko administration that the oligarch would not be touched.

But Akhmetov’s relations with Poroshenko are rather cold, analysts say.

Chornovil said that difficult relations between them are the reason why Akhmetov’s people are not appointed to government posts in Ukrainian-controlled Donbas.

Nevertheless, Akhmetov, who has a coal mine in the United States and two rolling plants in European Union countries, has had open doors to Western decision-makers, including former U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey R. Pyatt.

Despite his close relations with Yanukovych, Akhmetov has avoided coming under any Western sanctions.

The Americans are trying to negotiate with Akhmetov to broker a peace deal with Russia and reintegrate the occupied territories back into Ukraine, LigaBusinessInform, a news agency, reported last September, citing sources in Poroshenko’s administration.

Akhmetov wants to see the occupied territories back under Ukrainian control, political analyst Volodymyr Fesenko said. As the largest employer in the region, he could play a big role in winning over the hearts and minds of the local population by providing them an alternative to a devastating war: stable jobs, higher wages and other prospects.

“People in Kyiv, Moscow and I think many in Berlin understand that Akhmetov may become a key figure in this process,” Fesenko added.

Balázs Jarábik, a visiting scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said the Donbas conflict, which now involves Ukraine and Russia and is a security issue for Europe, is now too big for Akhmetov. Still, the oligarch could be and wants to be an important factor in finding a solution.

“Akhmetov is someone who is going be in backroom deals and willing to be in backroom deals,” he said. “It’s a funny situation for the king of Donbas to be kind of back, but in a back room.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter