Rhea Clyman, a Canadian journalist born in Poland, is finally getting more international recognition as the first and one of the few journalists who exposed the Holodomor, Joseph Stalin’s genocidal starvation of 4 million Ukrainians from 1932-1933.

Unfortunately, her stories in the Toronto Telegram, which closed in 1971 after a nearly a century in business, never got much international attention – until recently.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

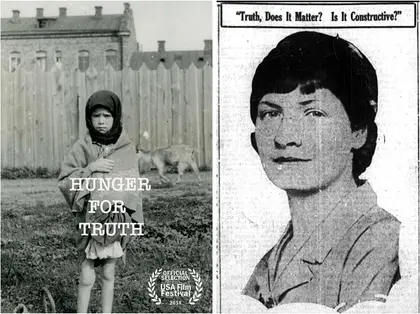

The documentary “Hunger For Truth: The Rhea Clyman Story” has been showing this month in Toronto.

A June 5 premiere at the Royal Ontario Museum included relatives of Clyman and Canadian Ambassador to Ukraine Roman Waschuk in the audience.

The Canada-Ukraine Foundation and the Holodomor National Awareness Tour produced the documentary.

The movie helps cement Clyman’s legacy as a heroic journalist who called attention to the Holodomor as Stalin’s apologists, including the New York Times’ Walter Duranty, were denying its existence.

The West, by and large, ignored the mass starvation in order to build relations with Stalin. “She is a hero,” Waschuk said during a June 25 interview in Kyiv.

The documentary is directed by Andrew Tkach. Waschuk called the documentary “very well-done” and says it does justice to Clyman’s life story.

The movie has English and Ukrainian versions. Waschuk said he’s interested in seeing “Hunger for Truth: The Rhea Clyman Story” shown in Ukraine soon.

“She had died in relative obscurity in New York. It’s really only a professor from the University of Alberta who started looking at her stories in the Toronto Telegram and Toronto Star and the Canadian press two years ago. The professor discovered 22 stories that she had filed in the Toronto Telegram in late 1932,” Waschuk said.

The professor who rediscovered Clyman’s stories is Jars Balan, a history professor who was researching Canadian coverage of the Holodomor and who reached out to Clyman’s relatives.

She wrote articles based on her trips to Kharkiv in eastern Ukraine and parts of Russia and the Caucasus. “She was really someone who had to overcome true challenges. She was run over by a streetcar in Toronto when she was 11 (and lost a leg). She was determined to become a reporter and found it was a boy’s club in Canada. She decided that becoming an international correspondent was her best chance for a career breakthrough and initially went to the Soviet Union with naive ideas that it would be a ‘worker’s paradise,'” Waschuk said.

She worked as a researcher for Duranty, the now-discredited New York Times reporter considered the dean of the Moscow press corps and a Stalin lackey.

When Clyman discovered that Duranty’s approach “doesn’t correspond with the way she saw reality,” Waschuk said, she set off on a car trip with two other women to discover the Holodomor. She was expelled from the Soviet Union for her coverage.

She went on to cover Nazi Germany and even survived a plane crash with other Jewish refugees to the Netherlands.

“It’s a truly gripping story. Her own relatives are active members of the Canadian-Jewish community,” Waschuk said. “Many of them who are in Canada were unaware of her past life and accomplishments. It’s been a voyage of rediscovery all around.”

According to a June 13 article in the Canadian Jewish News, Clyman, writing about Kharkiv in 1932, discovered that the city “was in the grip of hunger. Beggars swarmed round the streets, the stores were empty, the workers bread rations had just been cut.”

She also wrote of seeing emaciated corpses in the streets and of learning that children had been reduced to eating grass.

In the April 2 edition of Maclean’s, a Canadian magazine, Lisa Shymko writes: “The brave Jewish-Canadian correspondent— the first Western journalist to report on the forced famine — was accused by Moscow of spreading fake news and promptly banished from the USSR.

Like Clyman, a Welsh journalist by the name of Gareth Jones traveled to the Soviet Union and subsequently published his accounts of the forced famine ravaging Soviet Ukraine.

He, too, was banned from ever entering the Soviet Union again. Not long afterwards, Jones was shot dead in the Far East under mysterious circumstances believed to be linked to the Russian secret police.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter