There is one “villain” in the Vasyl Stus biopic “Censored” that Ukrainians would have wanted to have been named. But, due to legal threats, he wasn’t.

In a key film scene, Stus, the Ukrainian dissident poet, faces trial on charges of “anti-Soviet activity and propaganda” in 1980.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

His state-appointed attorney, Viktor Medvedchuk, does little to defend the poet and, in fact, agrees with the prosecution that Stus’ actions qualify as a crime.

The court sentenced Stus to 10 years in prison and five years in exile. Five years later, in 1985, Stus died at the age of 47 in a labor camp. At the time, the Ukrainian diaspora was trying to nominate him for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In the ensuing years, Medvedchuk grew wealthy in the media and energy businesses. He climbed the political ladder, serving once as Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma’s chief of staff and leading a political grouping known as the “oligarchs’ party.” He is now a lawmaker with the pro-Russian Opposition Platform — For Life party and Russian dictator Vladimir Putin’s right-hand man in Ukraine. He is sometimes derisively referred to as the “Prince of Darkness.”

When the authors of the film excluded the trial scene naming him from the original screenplay in August 2018, Ukrainian civil society demanded its return as an accurate portrayal of Medvedchuk’s poor representation of his client.

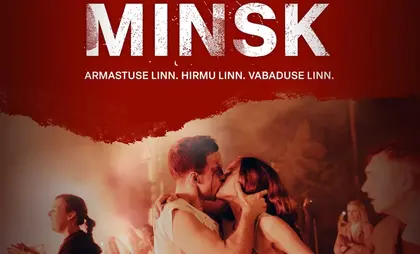

Film Exposes Bloody Protests of Lukashenko Regime

The government of former Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman backed the demand, since taxpayers paid for half of the film’s Hr 38.1 million ($1.5 million) budget. The trial scene in the original screenplay helped the film win the competition for state funding.

But Medvedchuk’s lawyer publicly threatened to go to court and get the film banned if it contained any “false information” about his client.

So as “Censored” premiered in movie theaters in Kyiv on Sept. 4, the 34th anniversary of Stus’ death, many watched attentively for the trial scene. It did show a Soviet court. It did show Stus demanding an international lawyer instead of “the second prosecutor” defending him. And it did show a character that resembles Medvedchuk.

“Comrades judges, I consider the qualification of the defendant’s actions to be correct,” the character says. These are the exact words spoken by Medvedchuk, according to declassified court transcripts. But the audience never hears the name “Medvedchuk.” The character is referred to only as “the defense” in the film.

The authors say they had to be careful not to change Medvedchuk’s recorded phrases in the slightest and could not use his name without his written consent.

Article 296 of Ukraine’s Civil Code allows the use of a living individual’s name in literary and other works only with his or her consent. Article 32 of the Constitution says that an individual can demand the refutation and removal of false information about him or herself. And Article 278 of the Civil Code says that, if an individual’s rights are violated in film, the court can prohibit its distribution.

In the U.S., portraying real-life individuals in fiction — politicians and historical figures, in particular — is allowed in most cases by the First Amendment to the Constitution. Last year, for example, the film “Vice” portrayed living former Vice President Dick Cheney as a power-craving villain. Cheney and his family did not sue the authors.

But clearly, it is another matter in Ukraine. Not only are the laws stricter, but also the film and distribution companies are less able to defend themselves in court. With a film industry that started to grow only in the last three years, the authors of the film simply can’t afford powerful legal defense, unlike Hollywood studios.

“With power and a good lawyer, the movie can be banned. That’s why the film came out in the only version that it had the right to come out,” “Censored” director Roman Brovko told the Kyiv Post.

So it remains for the viewer to recognize the real person behind the character of that state-appointed attorney.

And although the authors say they made the film for the wider public, young audiences in particular, they also say that most viewers in Ukraine will guess the name of Stus’ “second prosecutor” in the film.

Medvedchuk himself repeatedly defended his conduct as Stus’ attorney, saying that he could not save the dissident and acted in the framework of the law of the times.

A legal analysis of the case by lawyers in 2016 showed that Medvedchuk did not use the available levers that the defense had and violated lawyer’s ethics by admitting his client’s offense.

When recently asked whether he will go watch the film about Stus by the Ukrainska Pravda news website, Medvedchuk said: “Why? It doesn’t interest me. Like Stus himself.”

Rejection of Stus’ son

The film’s troubles started because of someone who was much closer to Stus. In the early stages of development, Vasyl Stus’ son Dmytro refused to consult with the authors of the film after reading the script.

“I refused to work with them, and that’s it. The screenplay is unacceptable — both for ethical and aesthetic reasons,” Dmytro Stus told Hromadske news website in August 2018.

Dmytro Stus initially refused to authorize the use of his father’s name, quotes and poems in the film. “Censored,” originally planned for release in February 2019, was in jeopardy. The Ukrainian Film Distribution company canceled the release in December 2018.

But in April, B&H Film Distribution announced that it had taken on the project and set a new release date. The screenwriter of the film, Artemiy Kirsanov, says that Dmytro Stus gave them the rights to use the name, poems and quotes of his father after all.

But Dmytro Stus said he would not watch the film.

What critics say

The critics have generally slammed “Censored” with negative reviews. Most have reprimanded the film for clumsy nationalistic propaganda that is, in one episode, chauvinistic toward Russian-speaking miners of Donbas, the working class of eastern Ukraine.

Most characters are lifeless and unconvincing, including the protagonist Stus, who seems like a stereotypical image of a Soviet dissident, without any individuality, critics say. The actors’ performance was mostly criticized as too theatrical and melodramatic.

“These are Soviet cliches turned inside out — like Soviet films made about any fighters against the system, (national poet Taras) Shevchenko or (Bolshevik) Russian revolutionary Kamo. We always see the same story. We are presented with some names and quotes, but there isn’t any individuality,” film critic Alexandr Gusev told the Kyiv Post.

Conversely, in one positive review shared by the screenwriters, the critic is delighted how the film tries to portray Ukrainian cultural figures, activists and dissidents.

“Stus himself turned out to be quite convincing. Sometimes in the film, one can see how a naive and kind guy turns into a tough and exhausted man,” writes Mykola Gerkaliuk, a journalist for the Vezha news website.

Historian and journalist Vakhtang Kipiani, who researched the trials against Stus, criticized the film for replacing real historical details with artistic fictions.

“The director, and it shows, wanted to shoot a thriller, but at the same time, he sacrificed the historical background, which is much more interesting and ‘cinematic’ than what he created. It’s a Soviet anti-Soviet film,” Kipiani wrote on Facebook.

A week before the film’s premiere, Kipiani released a book about the trial with court materials and his own historical articles. Medvedchuk sued Kipiani in defense of his “honor, dignity and business reputation,” demanding Kipiani refute “false information” about him in the book and calling for a ban on its distribution.

This is just one of dozens of Medvedchuk’s lawsuits concerning his defense of Stus.

“Stus is his pressure point. He actually wants to rewrite history, close everybody’s mouths, so nobody would think over his role in the trial against Stus,” Kipiani told the Kyiv Post.

“But the claim that Medvedchuk ‘killed’ Stus with his actions is senseless. He only participated in a conviction without a real trial as a small piece of the totalitarian system. He has to bear a moral responsibility for that,” Kipiani says.

After Kipiani wrote about Medvedchuk’s lawsuit on Facebook, his book sold out in online internet bookstores in a matter of hours, he says. Additionally, the author personally sold over 800 copies in four days.

Perhaps, thanks to Medvedchuk’s lawyer’s threats, more people will also go see the film.

And more people will definitely read the line in question from Kipiani’s book, which is as follows: “Was lawyer Medvedchuk afraid of the KGB or simply always a cynic and immoral character?”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter