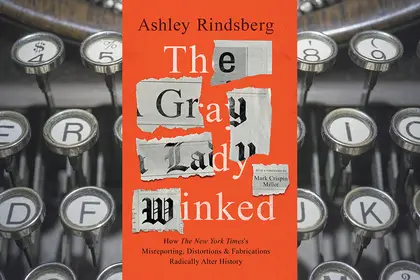

Walter Duranty’s shameful misreporting of the 1932-33 famine in Soviet Ukraine is just one of many large-scale failures in journalism committed by the New York Times, according to The Gray Lady Winked, a new book by Israel-based American author Ashley Rindsberg.

The book is a study of the biggest reporting failures of what many consider to be the United States’ paper of record. It invokes episodes ranging from the Gray Lady’s soft coverage of the Nazi regime in Germany to their fabricated interviews with families of soldiers who died in the Iraq War.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Chapter two, serving as one of the book’s main attacks on the high credibility often ascribed to the New York Times, covers the paper’s aiding and abetting of Walter Duranty, their Moscow correspondent from 1922 to 1936. Duranty is infamous for having consistently denied the existence of the famine in Ukraine in 1932 and 1933.

He won the Pulitzer Prize in 1932 for 13 articles he wrote in 1931. While the pieces under consideration did not cover the famine, the Pulitzer Prize Board in a 2003 review of Duranty’s award said the following: “Mr. Duranty’s 1931 work, measured by today’s standards for foreign reporting, falls seriously short.”

Ukrainian organizations in the United States and Canada have consistently lobbied for the revocation of Duranty’s Pulitzer. In 2003, the New York Times hired Mark von Hagen, a Soviet History professor at Columbia University, to recommend whether the paper should return Duranty’s Pulitzer. He concluded that “for the sake of The New York Times’ honor, they (the Pulitzer board) should take the prize away.”

However, ultimately the Pulitzer committee chose not to revoke the award, and the New York Times chose not to return it. The paper’s then-publisher, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., first claimed that the paper did not physically have the prize, a gold coin, and therefore could not return it. He then asserted that returning the Pulitzer would amount to a “Stalinist practice to airbrush purged figures out of official records and histories,” a statement which Rindsberg describes as “appalling.”

The line held by the New York Times is that Duranty was a rogue reporter who was guilty of “slovenly” reporting. However, Rindsberg believes that this is an attempt to cover up the paper’s wider involvement in the failure to report the story.

“The New York Times absolutely covered up a genocide. When it’s not entered into the historical record in that way, by the most powerful newspaper in the world claiming it didn’t happen, you miss something forever. You don’t have that same kind of energy behind those events,” Rindsberg explained in an interview with the Kyiv Post.

“The big lie behind Duranty is that he acted on his own. The real story is that nobody has asked the question of why Duranty would do this, and when you ask the question you come to the answer that he had no reason to do it. In fact, he only had reason to cover the story (properly), and then you say: why did it happen?”

For Rindsberg, the answer is that Duranty was likely pressured by those managing his newspaper: “You come to the answer that the New York Times instructed him to do it. They had much bigger interests at play, and part of those interests was getting the US government to recognize the Soviet Union.”

Rindsberg’s evidence for this, presented in the book, is an admission which Duranty made to a US Embassy official in Berlin in 1931: “’In agreement with the New York Times and the Soviet authorities’ his official dispatches always reflect the official opinion of the Soviet government and not his own.”

Israel-based American author Ashley Rindsberg is the author of “The Gray Lady Winked.”

This is a damning statement, for which the New York Times has been held fully accountable. Rindsberg concedes that there is a chance that Duranty, a skilled and prolific fibster, could have been lying to the official. However, he then points out that not only did his reporting on the famine very closely resemble the official Soviet position but that the New York Times also ran articles by writers who later turned out to be Soviet agents, such as Ella Winter.

In an interview, Rindsberg’s criticism of the Gray Lady is extremely strident, occasionally verging on polemical. Some of his assertions require a sizeable leap of faith. He maintains that the current iteration of the newspaper wants to propagate “socialist policies,” yet he cannot identify a smoking gun which would demonstrate why this is the case.

Nevertheless, the main body of his book is factual and well-researched and can be read as a reasonable case for the prosecution against the journalistic mistakes of one of the best-known newspapers in the world.

However, as is frequently the case with outsiders who take on bastions of the establishment, he has allowed himself to be dragged down by association. The preface of The Gray Lady Winked is written by Mark Crispin Miller, a New York University media studies professor known for his wild conspiracy theories about 9/11, the Parkland school shooting, and the Covid-19 vaccine.

When it comes to Ukraine, Miller has described the 2014 Euromaidan Revolution that ended Viktor Yanukovych’s presidency in 2014 as a “US coup,” stated that Vladimir Putin “didn’t seize Crimea,” and claimed that the post-EuroMaidan Arseniy Yatseniuk government contained “a number of unapologetic neo-Nazis.”

Ukraine-watchers will be familiar with all of the above attack lines, which are regularly pushed by the Kremlin, along with their witting and unwitting helpers on the fringes of Western media. All of the claims made by Miller about Ukraine had been thoroughly debunked long before he shared them.

When the Kyiv Post put Miller’s statements before Rindsberg, he conceded that he knew there was “some stuff out there” about the controversial professor, but that he “hadn’t done a full dive into all the allegations about him.” Rindsberg says that he disagrees with Miller on the Ukraine issue, as well as “about 10-20 others.”

He nevertheless defends the decision to have Miller write the preface: “I think that’s a part of this: being able to have this discourse with someone like Mark, and others who are involved with this project, who I disagree with on certain things.”

“The book is not about Russia and Ukraine per se, but is about media narratives, so that’s why I included the foreword.”

He also stated that part of the reason he enlisted Miller’s help was the lack of mainstream figures willing to criticize the Gray Lady: “At the end of the day, I wanted a dissenting voice on the New York Times, and it’s a difficult thing to find.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter