Ukraine has never been rich in oil.

But few people remember that the country used to possess enormous capacities to produce diesel fuel and gasoline. On the eve of the Soviet collapse in 1990, it had six giant refineries capable of refining 62 million tons of oil annually.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Not anymore. Currently, Ukraine has just two functioning refineries: the giant Kremenchuk Oil Processing Plant in Poltava Oblast and the tiny Shebelynka Gas Processing Plant in Kharkiv Oblast.

In 2018, they refined a modest 2.7 million tons of oil, 80 percent of which was extracted in Ukraine.

The other four refineries have stood empty for at least five years, gradually rusting and falling apart due to poor management and intense market competition.

“All these refineries were privatized absolutely stupidly: they were sold for a penny,” says Serhiy Kuyun, director of the A‑95 Consulting Group.

“For many years, the government has turned a blind eye to the fact that these refineries are not developing, while the rest of the world around us has already actively invested in the efficiency and quality of their refineries.”

Who supplies?

In 2018, the domestic Ukrainian market consumed 10.1 million tons of oil products. Out of these, only 1.7 million were produced in Ukraine, according to the annual report of state oil and gas company Naftogaz.

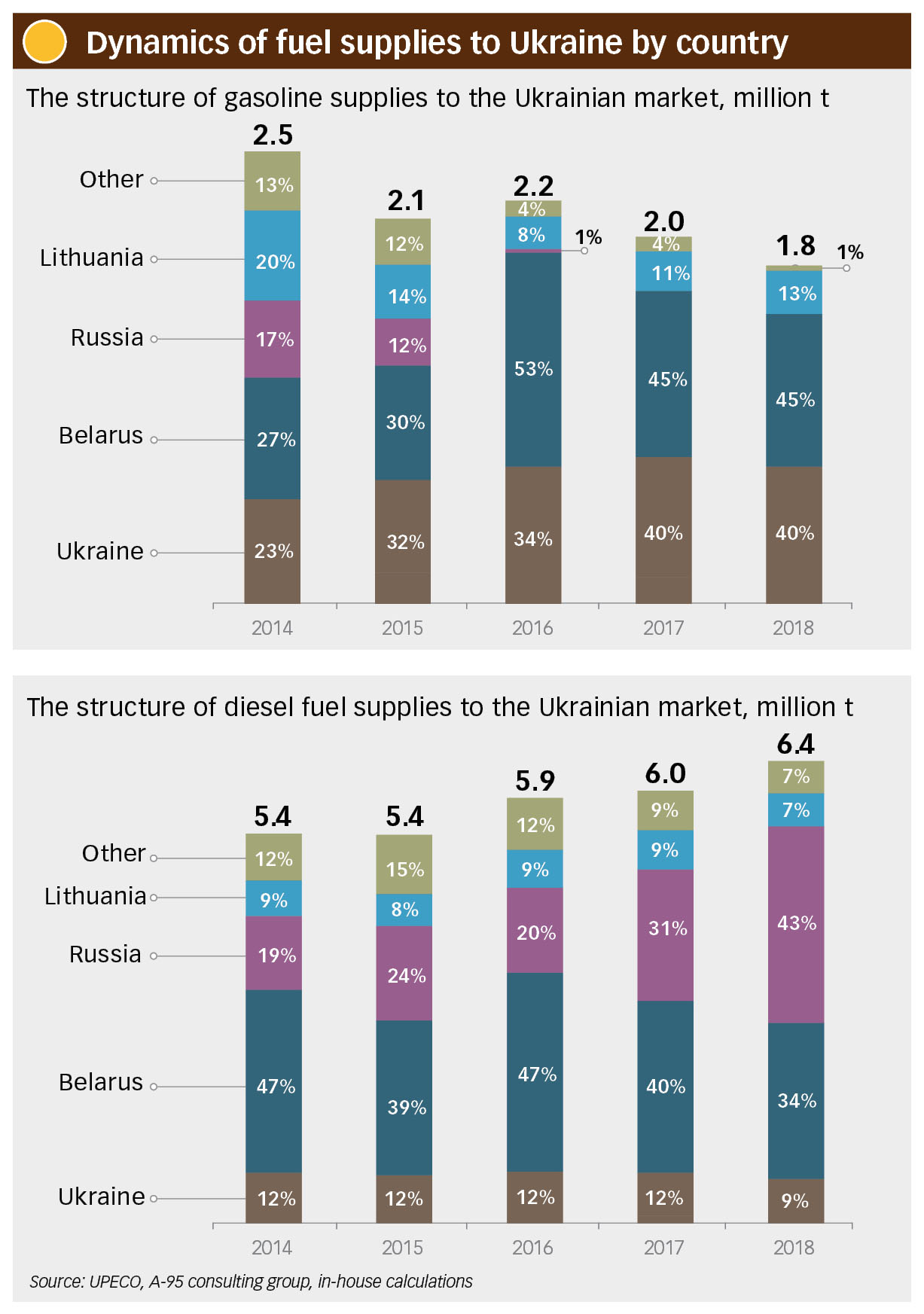

The remaining oil products — 84 percent of total consumption — had to be imported from Belarus, Lithuania and even Russia, a country with which Ukraine is at war. That automatically increases Ukraine’s energy dependence on its eastern neighbor.

Importing oil products cost the country $5.5 billion last year, which was 31 percent higher than in 2017, according to the State Fiscal Service.

The situation grew even more complicated when the Kremlin banned the export of crude oil and oil products to Ukraine on June 1, which forced the country to search for other ways to import oil and refine it.

The most recent episode in this saga came on July 6 when, for the first time in Ukraine’s history, 75,000 tons of U. S. Bakken crude was unloaded in the Odesa seaport and sent to the Kremenchuk refinery, which is operated by Ukrtatnafta.

That company’s shares are divided between Naftogaz, Ukrainian tycoon Oleksandr Yaroslavsky and to the informal Privat business group controlled by oligarchs Ihor Kolomoisky and Hennadiy Boholyubov. But only Privat group has the biggest influence since it has operational control over the company.

Another supplier of oil to Ukraine is Azerbaijan’s state-owned Socar oil and gas company, which has exported 320,000 tons to Ukraine since January, according to the Refinitiv Eikon industry analytical website.

Double-edged sword

Due to its small oil reserves, Ukraine has little chance to become independent from oil imports. But it can try to reduce its dependence on imported fuels.

“In theory, Ukraine can become an energy-independent state. Of course, the oil will be imported, but at least we will not import oil products,” says A‑95’s Kuyun.

But the only way to do this is to make the Kremenchuk refinery much more efficient. Ukraine’s other refineries have little chance for rehabilitation, experts say.

There is also no need to construct expensive, new refineries from scratch, a project that would cost around $7 billion — a price tag close to Socar’s $6.3-billion refinery complex, which opened last year in Turkey and can refine 10 million tons of oil per year.

“Those refineries that continue to operate are processing all Ukrainian oil and could refine 1.5 times more, but there is no sense in building something new,” says Oleksandr Kharchenko, director of the Energy Industry Research Centre.

According to Kuyun, Kremenchuk’s refinery would require nearly $1 billion in investment to improve efficiency.

“With deep oil refining processes at the Kremenchuk refinery, it is possible to produce up to 8 million tons of petroleum products per year,” he says.

The major issue here is the will of the owners.

Twelve years ago, the Privat group seized the refinery from Tatarstan’s oil company Tatneft using doubtful methods. Energy experts are sure that it was a raider attack.

Since then, nothing has been modernized.

“The plant is old and no one invests in it. And it is getting older and older. This means that fuel production is becoming more and more expensive,” says Kuyun.

Additionally, the latest financial report on the Kremenchuk refinery shows that it finished the year 2017 with a loss of Hr 2.44 billion ($94 million), its worst results in a decade.

However, Kharchenko believes that the numbers in the report could be falsified.

“It is possible to show any financial results in Kremenchuk under the existing Ukrainian accounting system. It’s only a matter of the financial director’s professionalism,” he says. “If they want to, they will show you a profit. If not, they will show you a loss.”

Even though the state has a 43-percent share in Ukrtatnafta, it cannot exert operational control over the refinery.

“Unfortunately, the state has not affected the management (of the refinery) for many years, when it comes to the Privat group and their ability to legalize corruption schemes, ensure their stable operation and lobby their interests,” says Kharchenko.

Ukrtatnafta did not respond to the Kyiv Post’s request for information on its investment plans and newer financial results. Kolomoisky also didn’t give any comment to the paper.

Biofuel

Ukraine also has other potential options to increase energy independence: biofuels made from plants.

According to the Ukrainian Association of Alternative Fuel Producers, also known as Ukrbiopalyvo, Ukraine’s incredible agricultural potential could allow it to stop importing oil from Russia and other post-Soviet countries.

Moreover, a shift to biofuel would increase Ukraine’s gross domestic product by $9 billion and sharply decrease carbon emissions.

But currently, that’s only a dream.

Bioethanol production at 13 factories across Ukraine reached a paltry 50,000 tons last year. But the Ukrainian government effectively killed biodiesel production in 2013, when it imposed the same excise taxes on it as on regular diesel fuel.

“Ukraine is a promising (country) for the production of biodiesel. We produce 3 million tons of rapeseed for Europe, from which they produce 1 million tons of diesel,” says Taras Mykolaienko, head of Ukrbiopalyvo.

But despite its impressive prospects, the biofuel industry feels strong resistance from fuel importers.

“Virtually all (regular fuel) imports are made of Russian oil,” says Mykolaienko. And the development of biofuel is “blocked by high officials. It is such sabotage.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter