Dissidents in Ukraine promoted the Ukrainian language and awareness of Soviet crimes, including the Holodomor of 1932-33 and the cover-up of the 1986 Chornobyl nuclear power plant explosion. Even traditionally passive workers in Ukraine’s industrial heartland staged mass protests.

In Moscow, the Communist Party was further challenged by elections of non-communist candidates to the Congress of People’s Deputies in 1989.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Sensing the end may be near, Soviet Union officials started resigning en masse.

Non-Communist Party candidates competed in parliamentary elections on March 4, 1990 in Kyiv for the first time in 70 years. Upon election, formed the Democratic Bloc, joined by defecting communists. In July 1990, Ukraine’s new parliament declared Ukrainian sovereignty, but stopped short of independence. However, that declaration was only a year away.

In the year between declaring sovereignty and independence, Ukrainians extracted concessions from Moscow while support for full independence grew.

Then in August 1991, hardliners within the Kremlin organized an unsuccessful coup against Gorbachev. With Moscow in chaos, Ukrainian politicians seized the opportunity. In a tense session on Aug. 24, 1991, Ukraine’s deputies voted 346 to 1, with three abstentions, to declare Ukrainian independence. The vote was later ratified on Dec. 1, 1991 by 92 percent of the population in a nationwide referendum.

Here are the words of some of the key people involved in the momentous change:

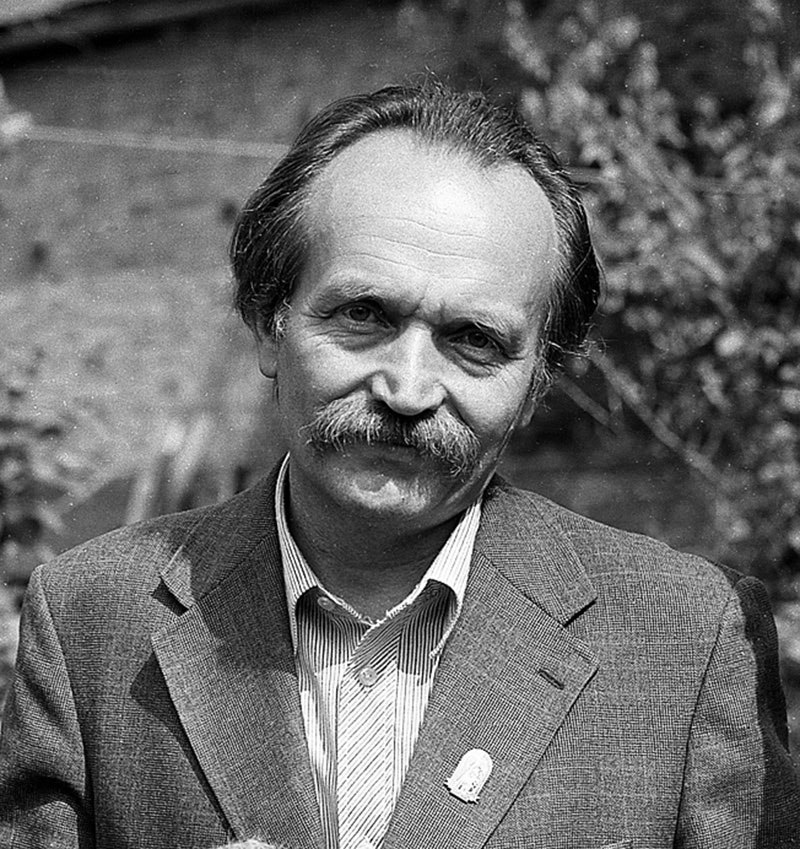

Viacheslav Chornovil

was a prominent Soviet dissident, imprisoned three times for a total of eight years. The first time was for documenting the illegal imprisonment of Ukrainian intellectuals. The second time was for publishing an underground magazine called the Ukrainian Informer and being involved in “separatist” activity. The final time was for “attempted rape,” charges that Choronvil vehemently denied and protested with a 120-day hunger strike. Chornovil was the leader of Rukh, a nationalist movement founded in 1989. He was one of the main challengers in the 1991 presidential elections to the first Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk.

Chornovil was killed in a car accident while campaigning for president in the 1999 elections. Ukraine’s Interior Ministry found no evidence of wrongdoing, but his supporters believe he was murdered. The following is an excerpt from a video interview he gave in 1996 to the Ukrainian Catholic University as part of a project on Ukrainian history from 1988-1991:

“First of all, people were ready for (independence) … it was a moment when the people rose. After that, I traveled all over Ukraine during the presidential campaign, and it was not only in the west – people in the east also believed in independence. But today the belief is smaller, which is (due to) bad leaders, who haven’t used the huge advantage of the people rising up.”

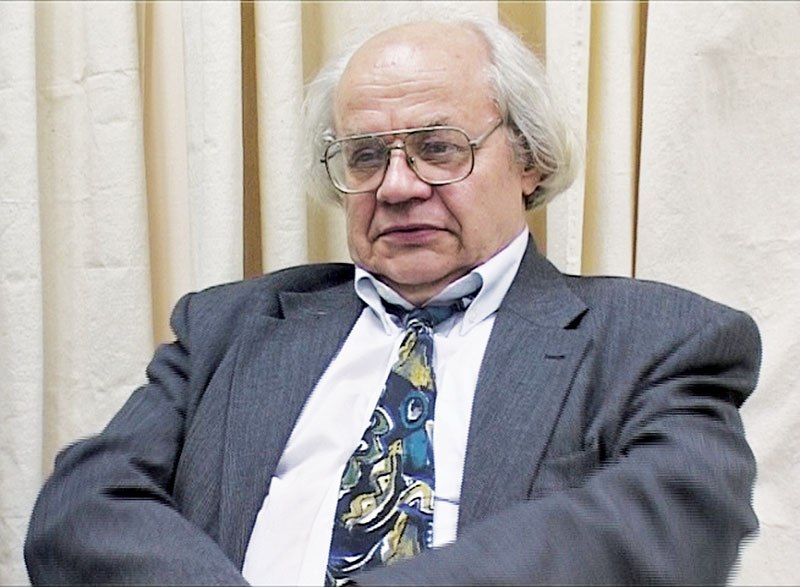

Levko Lukyanenko

was a Soviet dissident imprisoned for 15 years for creating an underground separatist organization. Upon his release from prison in 1976, he was a founding member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, a human rights organization, for which he was imprisoned again for 10 years. Lukyanenko was elected to parliament in 1990 and was responsible for writing the Declaration of Ukrainian Independence, which was voted for by parliament in 1991.

“Of the whole period, the most important moment for me was Aug. 24, 1991, when the Ukrainian Rada voted for the independence of Ukraine. After the vote, I walked out of the Rada to greet a huge crowd of maybe 20,000 people. There were so many people. They lifted me up. They thanked me. And I was so happy because what I had wanted and fought for all my life had happened. After that, we all went to the Maidan and again I spoke in front of a huge crowd of people, and by the evening on Sofiivska Square there was a meeting of all Ukrainians. People from all of the 25 oblasts came to Kyiv, and all the radio stations in Ukraine broadcast me reading out the declaration of independence to all of Ukraine. This for me was the greatest celebration and happiness.

“Things didn’t go the way they should have, because it turned out the communists weren’t Ukrainian patriots. They formed clans, and instead of the process of privatization, they started to steal everything for themselves. They stole the factories and plants. They ruined the factories and people were left without jobs. It’s very unfortunate. And this meant that Ukraine didn’t become a democracy, rather it’s about who has more money.”

Leonid Kravchuk

was a Communist Party ideologue before being made the Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic just before the collapse. Kravchuk managed to successfully hold power during Ukraine’s transition period, elected as the first president of Ukraine (1991-1994) in elections held in tandem with the referendum on independence in 1991.

“I was anticipating a new life because I knew the old system all too well. I was one of the leaders of the old Soviet Ukraine. I saw the difficulties people faced. They had no opportunities. I knew how to manage people, and together with them I started to build the new state.

“Unfortunately the expectations that I had couldn’t all be fulfilled, because there are lots of problems which aren’t dependent on Ukraine’s actions. Like, for instance, Russia’s war against Ukraine today.

The annexation of Crimea. I couldn’t have predicted back then that it would happen in 23 years time. The most important thing that we have is that the question of whether the state is independent is resolved. We have a state, and soon we will mark the 25th anniversary.

“Ukraine is developing. It’s difficult. There are problems.

“My most memorable moment from that period was when the Ukrainian parliament voted for the Declaration of Ukrainian Independence. You had to be there in the hall. The deputies were hugging each other, singing, lifting each other up. They celebrated on the streets. Lots of people came out onto the streets. Everyone was singing and celebrating. The act was supported by the majority of the parliament and so was constitutional. The event was the most striking moment of my entire life.”

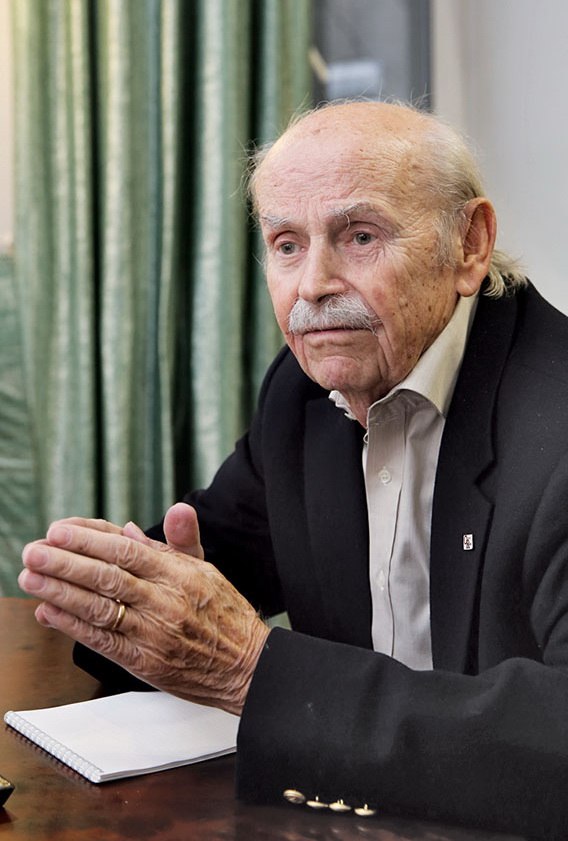

Ivan Drach

was a Ukrainian poet and political activist. Like Viacheslav Chornovil, Drach was born in Kyiv Oblast and developed his nationalist ideas at university, where he associated with other dissident-minded students. After a trip to Moscow in the early 1960s, Drach wrote his first anti-Soviet poems, but later, when several dissidents were arrested, he wrote an open letter in which he said he regretted his anti-Soviet activities. During “glasnost,” he founded Rukh along with Chornovil. The organization campaigned initially for greater freedoms, and was later key in campaigning for independence.

“I was in Moscow, listening on the radio what was going on in Verkhovna Rada in Ukraine. I saw how the double-headed eagle had been created around the Russian Parliament. And I recognized that this double-headed eagle would be pecking Ukraine much longer than next quarter of a century.

“I pay a lot of respect to the events of that day, as a people’s movement, which I headed at that time, did all it could to declare independence. I celebrate this day every year – 25 years in a row. I would like to recommend (the next generations) to rely on their brains and strength, and do not believe in the fairy tales that our generation believe in, while embracing this independence.”

Ivan Plyushch

was a Soviet deputy and was subsequently elected a deputy and speaker of the Ukrainian parliament. Plyushch authored the Declaration of Sovereignty that the Ukrainian parliament passed in 1990.

Plyushch died in 2014, at the age of 72. This is an extract from a video interview he gave in 1996 to Ukrainian Catholic University as part of a project on Ukrainian history from 1988-1991:

“The most important event was the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine. It was on July 16, 1990, and it was the beginning. First, came the will of the highest body, the Verkhovna Rada, to be independent. Second, came the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine on Aug. 24, 1991. And third was the independence referendum on Dec. 1, 1991.”

“It was a fateful decision, and I have repeated, am repeating and will repeat that Ukraine is happy because of that. Well, I’m financially secure today, I’m in a better position. But I have talked with people who aren’t as in such a secure position as I am. They tell me ‘Mr. Plyushch, we’re ready to go about without clothing for three years, but have Ukraine.’ So, I’m happy for those people, as well as for myself. I wonder if people (who argued against independence) remember that even if they had the money for a car, the car could only be bought if you had connections, or if you waited in a line for more than 10 years. They’ve all forgotten about that.”

Vyacheslav Kyrylenko

was a student activist and one of the initiators the Granite Revolution against strengthening ties between the republics of the Soviet Union in October 1990. The Student Union, of which Kyrylenko was a leader, organized several mass protests in the lead up to independence. A core group of 200 students participated in the hunger strike on Kyiv’s central square, which lasted for 16 days, while dozen thousands of others camped there in support. The students erected around 50 tents and occupied Kyiv’s central square, which was later renamed Maidan Nezalezhnosti, and which was the focal point of the Orange Revolution in 2004 and the EuroMaidan Revolution in 2013-14. The activists opposed the signing of a new union agreement, as proposed by Moscow, to bind the republics of the Soviet Union more closely together. Multi-party parliamentary elections and the nationalization of Communist Party property were also among the activists’ demands. The peaceful protest led to the dropping of the proposed union agreement, multi-party elections, and the resignation of the head of the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Vitaliy Masol.

“When the Soviet coup started in Moscow, activists of Ukrainian Students Union and those who started the hunger strike launched some resistance. People gradually gathered on the Maidan (Independence Square). But thank God the coup was defeated, and the parliament in an emergency session proclaimed the Act of Independence under pressure from the citizens, and at the same time because many of them (the communists) were afraid of an uprising. I was among those who stood outside (the parliament building). We knew many of the lawmakers, and found out that the act had been written. Then the Ukrainian flag was raised over the parliament.

“However, when we came back to Kyiv on Aug. 19, we had completely different thoughts. We thought that dark times were coming to the country for everyone. But five days after the coup (in Moscow) … independence was declared.

“For me, it is the greatest holiday, which I celebrate every year. But – no matter who is in charge of Russia, but especially now with (Russian President Vladimir) Putin – every year it is a difficult experience for Russia to see that Ukraine is still an independent state. We have to fight for independence and sovereignty every day, because the Russian Empire will be (located) close to us forever.

“These were the most important events in my life in political terms. Because, after many hundreds of years of struggle, Ukraine managed to declare independence without bloodshed. But nothing happens without blood. A war for independence is taking place now. But now we have a grown up generation, born after 1991, and so nobody will be able to take (our independence) with their bare hands.”

Bohdan Hawrylyshyn

is Ukrainian-Candian an economist, expert on issues of public administration and international business, and lecturer at several universities in Canada and Switzerland. He has also served as an advisor to the Ukrainian government. His current activity is concentrated around philanthropy in Ukraine’s next generation. Hawrylyshyn as was present the day of the vote

“The day before (the vote for independence), I heard that there would be a special session of Verkhovna Rada. I managed to order a plane ticket (from Geneva), went directly from Boryspil (airport) to the Verkhovna Rada. There was a break in the session. Seven people were sitting around a round table outside the office of the chairman of the Verkhovna Rada. They invited me to join them. The subject under discussion was what to call the country that we would declare independent:

The Democratic Republic of Ukraine, the Republic of Ukraine? I simply said: “Why not call it Ukraine?” There was instant agreement.

“The most important part of the celebration for me was when we looked out of the windows of the second floor of the Verkhovna Rada, where an enormous crowd had gathered around the building, all beaming with pride and joy.

“I still feel very elated that such an important decision was made so quickly, spontaneously, unanimously.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter