Few people in Warren, Ohio or Mason County, West Virginia have ever heard of Ihor Kolomoisky. Yet both U.S. cities are home to steel plants that have been run by the Ukrainian oligarch for more than 10 years.

Kolomoisky used the plants as keystones of an attempt to corner the global ferroalloy market, building an empire that extended from the American Midwest to the Australian outback and back to the ferroalloy plants along the Dnipro River.

The buyouts led Kolomoisky’s companies to, at one point, control more than 40 percent of the world manganese trade and more than half of the United States’ output of silicomanganese – a crucial resource for forging structural steel.

But with the recent fall in global commodities prices and the Ukrainian government intent on reining in oligarchs, Kolomoisky has been put on the retreat.

One of the main holding companies for the Dnipro, Ukraine, native’s U.S. factories has declared bankruptcy, while his biggest Australian mining venture, which included operations in Ghana, was sold to Chinese investors in November last year – along with the company’s $400 million debt.

“Kolomoisky has suffered significant losses, but he hasn’t lost everything,” said Volodymyr Fesenko, head of the PENTA political research center in Kyiv.

Court filings reveal that Kolomoisky was divvying up and fighting over the rusting U.S. steel mills with other Ukrainian oligarchs – in the same way that they fought over Ukraine’s Soviet-built industrial plants in the 1990s and 2000s. One deal, involving Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich, bled into the sale of a Warren, Ohio steel mill.

Much of this is revealed through legal filings made by Vadim Shulman, a Krivyi Rih businessman and partner of Kolomoisky, who fell out with him over a deal gone wrong involving Warren, and who has filed subpoenas in several U.S. states as apparent warning shots in preparation for a potential later lawsuit. Shulman also sued Kolomoisky directly in the United States, demanding $3 million in damages before a judge dismissed the case.

Kolomoisky, whose network of companies is called Privat Group, is undergoing financial troubles that echo those of the communities where he ran factories. Many of his assets have now shut down or scaled back production as Privat Group undergoes financial tremors in the wake of the nationalization of PrivatBank, the empire’s “core,” Fesenko said.

Pat Gallagher of United Steelworkers in Warren, Ohio, said Warren supplied around 200 jobs. “It’s a loss to any community when you lose that,” he said.

An employee of Felman Production, a West Virginia silicomanganese plant controlled by Kolomoisky, said that the company doesn’t receive enough money to operate safely.

Kolomoisky did not comment.Jason Chudoba, a spokesman for his U.S. firms, declined to comment.

American empire

The story of Kolomoisky’s American empire begins in the late 1990s.

Shulman, a Krivyi Rih businessman with Jewish roots, had built a coke fuel fiefdom over the course of the decade. In 1999, Shulman told Forbes in a November 2012 interview, he was the main coke supplier for Dnipro’s Evraz metallurgic factory, then known as Petrovsky.

Kolomoisky and Shulman went in together to buy a stake in the plant from the government in 2001, after befriending each other on a trip to Israel.

But they faced a problem: Petrovsky was full of dilapidated, Soviet-era equipment, making it hard to run.

The Ukrainian businessmen looked to America’s industrial Midwest. At the time, an Ohio steelmaker called CSC had declared bankruptcy after investing $100 million into its Warren, Ohio plant.

According to a U.S. court filing, the two businessmen, along with Kolomoisky partner Gennadiy Bogolyubov, saw the purchase as a chance to “break the plant down, and transport it to Ukraine where it would be reconstructed and thereafter carry on the steel-making business.”

Shulman bought the plant for $13.5 million in 2001, before he, along with Kolomoisky and Bogolyubov, each invested $30 million.

Yet years later, Shulman would come to regret the venture. He later alleged in court that he had been cheated out of his stake through a campaign of insider lending that saddled him with tens of millions in debt, while Kolomoisky and Bogolyubov robbed the company.

Silicon ambitions

By the late 2000s, Privat Group had all but consolidated its hold on Ukraine’s ferroalloy market, taking total control of the country’s manganese supply, as well as that of Georgia.

The businessmen began to look abroad.

In 2008, Privat Group bought one of the world’s largest manganese miners, Australia’s Consolidated Minerals (Consmin). Between its Australian and Ghana operations, it controlled around 10 percent of the world’s manganese ore supply.

Bogolyubov bought the company for $1.1 billion after defeating former BHP Billiton CEO Brian Gilbertson’s Pallinghurst Resources in a 2007 bidding war.

Glenn Stedman, a Queensland shareholder with a then-sizeable Consmin stake, launched a campaign against Pallinghurst’s bid, calling on shareholders to hold out for a better offer.

Bogolyubov swooped in with that rival offer through an offshore company called Palmary Enterprises, winning shareholders over by sweetening the deal to $5 per share.

“It was a hostile takeover but I think Palmary was the most honorable (bidder),” Stedman said.

Bogolyubov then set out to expand his share of the global manganese market through OM Holdings, which held five percent of the world supply through its Bootu Creek mine.

In November 2008, Bogolyubov spent a reported $27 million to buy an 11 percent stake in OM Holdings.

But OM Holdings beat back the takeover attempt. Privat Group sued OM Holdings to force the takeover through a subsidiary called Stratford Sun Limited, but lost that case as well.

OM Holdings executive chairman Low Ngee Tong, in a 2012 interview with The Edge Markets, said the Ukrainian billionaire planned to ‘gain significant control over Australia’s manganese output’ by combining OM with Consmin.

Stedman, who also has a stake in OM Holdings, agreed Privat was trying to corner the country’s manganese industry.

After the Australian acquisitions, Privat Group came to control up to 40 percent of the world manganese market, some estimates reported.

Back to Warren

Kolomoisky’s ferroalloy business formed a large part of PrivatBank’s loan book, taking up around 20 percent – Hr 35 billion ($1.3 billion) – of the bank’s loans, according to Anastasiya Tuyukova, a Dragon Capital banking analyst.

Though it is unclear exactly how much of that money sloshed around Privat Group’s U.S. and Australian businesses, court documents show that the organization’s U.S. companies lent tens of millions of dollars to each other internally.

According to an audit of Warren Steel reviewed by the Kyiv Post, the company accrued $60.8 million in related party loans.

Shulman, the former Kolomoisky partner, alleges in court filings that the related party loans were used to rob him.

In 2008, Shulman claims, he was part of a deal between Kolomoisky and Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich, who owns international steelmaker Evraz.

News reports from the time point to the sale of Dnipro’s Petrovsky factory as the centerpiece of a purported deal in which Kolomoisky and Shulman were to sell a stake in the plant to Evraz, along with other coking and iron enrichment plants. In exchange, Privat would get a significant, undisclosed stake in Abramovich’s conglomerate.

But a disagreement over share payouts reportedly saw Kolomoisky forcibly retain control over Ukraine’s southern iron enrichment plant after it was supposed to be transferred to Abramovich, souring the deal.

Legal filings say that Kolomoisky injected $30 million into Warren Steel in 2008 as part of the deal with Abramovich.

But as the years went on, Shulman claims in the filings, Kolomoisky began to use Warren to loan himself tens of millions of dollars from his other companies.

Shulman, apparently unaware of this, found himself in September 2014 to be holding as much as $173 million in debt through the company.

Another of Kolomoisky’s U.S. companies, Optima Speciality Steel, filed for bankruptcy in December over $260 million in unpaid loans, taken out to finance expansion that saw Optima buy out five separate factories across four states.

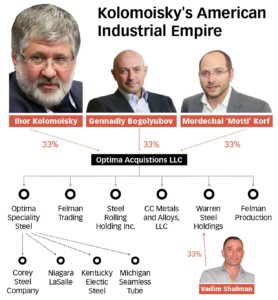

Kolomoisky and Bogolyubov set up Optima Acquisitions in June 2008 to manage the investments. According to a bankruptcy filing, the company is one third owned by Kolomoisky, Bogolyubov, and a Florida man named Mordechai “Motti” Korf.

Korf, who did not reply to requests for comment, appears to have been linked to Kolomoisky’s business in Ukrnafta. Optima Management, a firm run by Korf’s brother-in-law and two-thirds owned by Privat Group, is the largest property owner in central Cleveland.

Insider loans

Many of Kolomoisky’s companies appear to have been mismanaged.

Workers from Felman Production told the Kyiv Post that injuries at the facility were common, due to a lack of maintenance and management’s refusal to supply them with equipment, citing “cost concerns.”

Dozens of civil lawsuits were filed in West Virginia federal court alleging malpractice in the company’s treatment of workers before the Occupational Safety and Health Administration fined the firm for malfeasance in 2009.

The billionaire met with U.S. federal law enforcement while on a one-time visa in 2015, during which he went to basketball games, according to a Facebook post by BPP deputy Serhiy Leshchenko.

Other events in recent months appear to have left Kolomoisky on the defensive.

Warren Steel, deep in debt, closed in early 2016. Woodie Woodie in Australia closed nearly simultaneously, as did one of Kolomoisky’s assets in Georgia.

Weeks before PrivatBank was nationalized, Consmin was sold to a Chinese firm at an undisclosed price.

The company had an inside loan balance of $737.5 million at the time of the most recent financial disclosure, two months before the sale.

Peter O’Connor, an Australian investment analyst, called the sale genius, saying the manganese market was recovering at the time. It’s not clear that Privat’s nationalization hurt Kolomoisky at all.

Others argue that the bank’s web of inside loans has begun to catch up with Kolomoisky.

“Kolomoisky outsmarted himself,” said one insider.

But for the oligarch’s West Virginia workers, that comes as little comfort.

“It’s a day to day question of, ‘are we gonna be working tomorrow?’” said a Felman employee.

“Are there gonna be orders for material? Or is it gonna end up being, ‘Hey! You’re being laid off.’”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter