Editor’s Note: The following article is part of the Ukraine Oligarch Watch series of reports supported by Objective Investigative Reporting Program, a MYMEDIA project funded by the Danish government. All articles in this series will be available in English, Russian or Ukrainian can be republished freely with credit to their source. Content is independent of donor.

Ukraine’s enigmatic gas billionaire lost his position at the top and much of his wealth after the EuroMaidan Revolution that drove his ally President Viktor Yanukovych from power. Still in exile in Vienna fighting U.S. criminal bribery charges, he has vowed to return to Ukraine and influence events, but his prospects of a comeback are getting slimmer all the time.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Story at a glance:

Dmytro Firtash appeared from nowhere to secure an almost 50 percent share in gas deals between Russia and Ukraine, worth billions of dollars.

He has always passed off his past connections to notorious Kyiv-born organized crime boss Semion Mogilevich as “coincidence” but many, including U.S. authorities, think there’s more to it.

With his wealth, Firtash has bought up Ukraine’s fertilizer and titanium plants, as well as media assets, which he uses to maintain his position from exile in Vienna.

He is currently awaiting the U.S. appeal on a rejected extradition request to face charges in Chicago for bribery. Spain has also filed extradition papers for Firtash to face trial for alleged money laundering. He’s becoming the oligarch who can’t, and may never, come home.

Dmytro Firtash

Date of birth: May 2, 1965

Place of birth: Sinkiv, Ternopil Oblast

Wealth: $665 million, 9th richest person in Ukraine, according to a 2016 estimate by Focus magazine. Down from $2.7 billion in 2013.

Key Assets: Group DF, a conglomerate comprising regional gas distribution companies, titanium and fertilizer plants. The group also has several television channels: Inter TV, K1, K2, NTN, Mega, Enter Film, Zoom and Pixel.

Personal: Married to his third wife Lada Firtash. Has three children: Ivanna from his first marriage and Anna and Dmytro with his current wife.

Praised for: Donating $5.4 million to the University of Cambridge Ukrainian Studies programs and funding scholarships for Ukrainians to complete masters degrees at the university. He has given $4.5 million to the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv. He also donated $2.5 million to the construction of a monument to the Ukrainian Famine (1932-33) in Washington.

Criticized for: Amassing wealth through non-transparent gas deals from the late 1990s to 2013 and his businesses links to reputed organized crime figures and to Russia. The most lucrative and controversial period was from 2004 to 2009 when his company RosUkrEnergo, was the sole gas intermediary between Central Asia, Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

STORY STARTS HERE:

On New Year’s Eve 1996, the future Ukrainian oligarch Dmytro Firtash was lying on the floor of Hardrock restaurant in the western Ukrainian city of Chernivtsi, wearing a tracksuit and wondering if he would survive. He’d just been shot by a drunk local gangster during an argument. His friend and long-term business partner from Moscow, Oleg Palchikov, was the only witness not too squeamish to stop the blood pouring out of his stomach by sticking his fingers into the wound.

Two decades and billions of dollars later, Firtash’s business dealings have led him on a rollercoaster ride that put him in the center of heavily politicized multibillion-dollar natural gas contracts between Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia and Europe. But it seems to have braked in Vienna.

Firtash would not be interviewed for this story.

He is currently awaiting the U.S. government appeal of a lower judge’s refusal to extradite him to face trial in the American city of Chicago for bribes allegedly paid by him to Indian officials for a titanium plant.

Firtash has not been able to leave Vienna since he was arrested in his mansion at the request of the U.S. FBI in March 2014. Despite an Austrian court ruling in agreement with Firtash that the U.S. extradition request was politically motivated, the risk of leaving Austria is too high.

Indeed, some claim that Austria is especially motivated to protect Firtash because of the involvement of Austrian banks in his business dealings. Meanwhile, some of Ukraine’s current authorities have threatened Firtash with arrest if he sets foot back on home turf.

The story of how Firtash started as a driver in the mid-’90s, became one of the world’s top gas traders who walked the corridors of the Kremlin and rubbed shoulders with three successive Ukrainian presidents, and then turned into the oligarch who can’t come home, is one of the greatest enigmas of independent Ukraine.

He came from nowhere

Firtash first came under the spotlight in March 2006 when Russia’s Izvestia newspaper reported that he stood behind 45 percent of a gas supply company called RosUkrEnergo. The Ukrainian ownership of the company, which won the contract to control the supply from Russian and Central Asian producers to Ukraine and onto Europe, had been obscured until then by Austria’s Raiffeisen Investments. They also reported Ivan Fursin, a lesser-known Ukrainian businessman, held Ukraine’s other 5 percent. Russia’s Gazprom openly owned its 50 percent.

At some points, Swiss-registered RosUkrEnergo made as much as $2.5 billion a quarter as the intermediary between Kyiv and Moscow, whose state-controlled gas companies could have brokered direct supply contracts. But for 20 months after the company was created, and four years after he entered the gas business, Firtash was a person only whispered about in the back rooms of Naftogaz, Ukraine’s state gas company. Few people knew his name and even fewer had met him, a former Naftogaz analyst, Dmytro Marunych, told the Kyiv Post.

Despite keeping a low profile, Firtash had reached the top enclaves of political power as early as 2001. By the March 2002 parliamentary elections, he ran as one of the top candidates for the party “Women for the Future.” The party was under the patronage of Ludmila Kuchma, wife of then- President Leonid Kuchma. “Women for the Future” failed to win seats in parliament, arguably not helped by some of its candidates’ total absence from public life.

In fact, the Ukrainian people had no idea what Firtash looked like until The Financial Times published the first picture of him in 2006.

Firtash’s “coming out,” however, failed to dispel a rising number of accusations that he was involved with Semion Mogilevich, an infamous Kyiv-born organized crime boss who was for several years one of the FBI’s 10 most wanted fugitives. Despite ample evidence, Firtash stringently denies ties to Mogilevich.

The FBI tied Mogilevich to a stock market scam worth millions of dollars in the U.S. but, according to them, and several European police agencies, he has also been a major player in women, arms and drug trafficking as well as natural resources. FBI Supervisory Special Agent Peter Kowenhoven told CNN in 2009 that Mogilevich is so powerful that “he can with a telephone call affect the global economy.”

All a coincidence

Firtash is from western Ukraine’s Ternopil Oblast and professes humble beginnings as a tomato grower, fire station worker and driver. It was as part of his work as a driver, according to his official biography, that he began to sell food to Central Asia through barter arrangements common in the post-Soviet 1990s with his second wife, Mariya Kalinovska (they divorced in 2005). After securing high-level contacts within the Turkmen government, he has said, they started to work in the gas supply business. From around 2001, they quickly overtook the main existing intermediary supplier, Russia’s Itera, and sealed control over the Ukrainian market and more importantly over exports to Europe. The story makes earning billions look easy.

Firtash’s companies involved in the gas trading business and related barter payment schemes that preceded RosUkrEnergo were of a similarly opaque nature. Both had links to Mogilevich.

Depositors of Dmytro Firtash’s Nadra Bank protest outside one of its branches in Kyiv in April 2010. Nadra Bank suffered from liquidity problems for several years because of poor management and insider lending. It was liquidated by the National Bank of Ukraine in June 2015. (UNIAN)

Depositors of Dmytro Firtash’s Nadra Bank protest outside one of its branches in Kyiv in April 2010. Nadra Bank suffered from liquidity problems for several years because of poor management and insider lending. It was liquidated by the National Bank of Ukraine in June 2015. (UNIAN)

Highrock

The first was Highrock Holdings in 2001. Following this there was Eural Trans Gas, a Hungarian company created into 2002, which won a contract to supply Ukraine with the Turkmen gas that came through Russia. It replaced regional gas supply giant Itera, controlled by Turkmenistan-born Igor Makarov.

Firtash was director in Highrock between 2001 and 2003. From 2002, Firtash and his ex-wife Kalinovska owned a third directly. By 2003 he acquired another third of the company through Cyprus-registered Agatheas Trading.

Galina Telesh, who according to the Hungarian authorities married Mogilevich in 1995, also held a one third stake at through Agatheas until Firtash took it over in 2003. The company was registered by Olga Schneider, who the Russian authorities say is Mogilevich’s Russian wife.

In addition, Igor Fisherman, the man who the FBI have long considered Mogilevich’s closest partner, had his car registered to the same Moscow address as Highrock. Firtash claimed to the Financial Times in 2006 that he bought into Highrock Holdings through Itera not knowing that Mogilevich was involved and quickly bought out Telesh’s shares when he found out. But Makarov denied having any links with the company and none have surfaced.

Eural Trans Gas

The second company, Eural Trans Gas, was registered by a lawyer named Zeev Gordon who arranged for shares to be owned by three random Romanians. The company’s director was Hungary’s former communist Culture Minister, Andras Knopp. Gordon told anti-corruption NGO Global Witness in 2005 that he created the company on instructions from one Dmitry Vasilyevich Firtash. Gordon also represented Mogilevich at the time.

Firtash only later admitted to owning Eural Trans Gas, but never explained to the satisfaction of critics the roles of the Romanians and Gordon. And according to Firtash, Gordon had many clients “because he is a criminal lawyer.”

Documents obtained by Global Witness show Eural Trans Gas was a joint venture between Naftogaz and Gazprom, although neither side owned shares on paper. Further evidence of this is that the day the two sides announced a new joint venture, Eural Trans Gas was created as a new supply company. In an interview with the Kyiv Post in 2003, Knopp confirmed that it was a joint venture and said that the nominal owners were just part of the “restructuring process.” However, instead of being passed onto the two state companies, it ended up being controlled by a complex network of offshore.

These revelations led the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine in 2003 to publicly say that he was of the belief that Eural Trans Gas was linked to organized crime groups.

Firtash later claimed that these links to Mogilevich are circumstantial and places the blame on Itera’s Makarov but admitted in a meeting with the U.S. ambassador in 2006, which Knopp also attended, that he had worked with Mogilevich.

Arbat Prestige

A further look into Firtash’s business history shows more links between him and Mogilevich together with Kalinovska. Kalinovska is said to have introduced Mogilevich and Firtash, having met the latter through her first husband Zinoviy Kalynovsky.

Kalinovska told Ukrainska Pravda in 2007 that they jointly owned a 16.5 percent stake in Arbat Prestige from 2002, the biggest perfume business in the former Soviet Union. Arbat Prestige was reported to be owned by Mogilevich and his partner Vladimir Nekrasov. The pair was arrested for tax evasion charges relating to the perfume chain in 2008 and subsequently released.

Firtash and Kalinovska’s alleged minority stake was held by lawyer Elena Yargina through a Russian company, Rinvey. Firtash continued to employ Yargina until at least 2007. Corporate records show that Olga Zhunzhurova, the wife of Fisherman, and Mogilevich’s then wife, Telesh also each held 16.5 percent in Arbat Prestige through Rinvey. The remaining 50 percent was controlled by Russian businessman Nekrasov.

In an interview with The Financial Times in 2006, Firtash said that Yargina had joined Rinvey at his direction but he said he could not remember why he had asked her to do so. He also said he had no involvement in Rinvey, its business and no ties to its other owners.

The Guarantor

Observers, experts and insiders claim access to the kind of gas contracts Firtash had, yielding access to the prized markets of Ukraine and Europe, don’t come without relationships with those at the very top of political power from Moscow, to Kyiv and Central Asia. How those relationships were formed is the greatest unknown when it comes to Firtash.

In 1995, Firtash was arrested and jailed for three months in Chernivtsi for running a trucking business which smuggled contraband alcohol, according to the former journalist, now member of parliament Mustafa Nayyem, who wrote extensively about Firtash. Palchikov, the man who saved his life and would become a director at RosUkrEnergo, was also arrested. The then regional chief of police Ivan Mirniy who reportedly oversaw their release went on to be Firtash’s bodyguard and now serves as a parliament lawmaker. Firtash has always denied being arrested and being involved in alcohol smuggling.

Tom Warner, the Financial Times journalist who carried out one of the first investigations into Firtash’s gas businesses, told the Kyiv Post that he believes Firtash is “the new face of the Mogilevich group.” Firtash would never have got into the gas business if it was just him, said Warner. According to Warner, Firtash achieved something between 1995 and 2001 which made him important enough to get a one third stake in Highrock:

“He must have somehow become important to the group. He must have been a good manager and been involved in something that was making a lot of money. The way these groups work is you earn money, you move up. Before he got to the point where he’s got an equity stake in a company which buys a fertilizer company (Tajikazot purchased by Highrock in 2002) in Tajikistan. He must have already been earning money, running some operation for the group which was earning good money.”

Warner’s theory is that Firtash’s involvement comes from the use of figures like Mogilevich during the 1990s and early 2000s in business deals to take out the side who broke the deal, otherwise known as a “garant” or a guarantor.

“Eural Trans Gas was a three-way deal among (Russian President Vladimir) Putin, Kuchma and Mogilevich. Why they decided to get rid of Itera and Mogilevich was the guy to give it to is a very good question. There were other things that Mogilevich was doing. Other things that made him important,” said Warner.

As Eural Trans shares were never held directly by either parties, Warner’s theory is difficult to prove. However, in recordings made and released by Kuchma’s bodyguard Mykola Melnychenko, a voice resembling that of Kuchma discusses Mogilevich a total of five times on a range of subjects, including the fact that he worked as an informer for the Ukrainian and the Russian Security Services — for which according to the recordings, Mogilevich was awarded a Russian passport when he fled Hungary. (Editor’s Note: The transcript of this recording and others appears in the book by Jaroslav V. Koshiw, “Abuse of Power: Corruption in the office of the president.” The author is an ex-Kyiv Post editor and father of the author of this article).

Mogilevich’s relationship with Kuchma and Putin was further revealed by a collection of leaked intelligence documents from the Israeli and Hungarian authorities, which indicated he was used to launder money for the elites of the Soviet Union.

Presidential business

“The gas and oil business has always been considered ‘presidential business’…That’s how you made crazy money,” Oleh Rybachuk, chief of staff to former Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko, told the Kyiv Post.

RoskUkrEnergo, and Eural Trans Gas before it, were just that: joint ventures created by presidents Kuchma and Putin, according to Rybachuk. Their existence was hard to justify.

Why not just supply from one state gas company to another? After all, it is the state that owns the means of production, pipelines and storage centers and, therefore, the states should benefit from any profits. Why does anyone need a Firtash figure, not least Ukraine, Russia and Turkmenistan, who 15 years previously operated as a single country? And either way, why did Ukraine’s Naftogaz not own half of the joint venture, like Russia?

The official explanation from Russia was that it was too hard to get Ukraine to pay on time. An intermediary company with knowledge of the market took away this risk, it was said. Another factor widely propagated by Ukrainian officials was that RosUkrEnergo, and intermediary companies in general, were able (through unknown means) to secure a better price for Ukraine than Ukraine could secure itself. This was true. The company, some argue, supplied Ukraine with gas below-market prices.

The existence of RosUkrEnergo was something that puzzled even the likes of Rybachuk who was close to Yushchenko since their time at the National Bank of Ukraine. Unable to find a satisfactory answer at home, Rybachuk took the opportunity to ask Yushchenko’s then-Russian counterpart Dmitry Medvedev on a trip to Moscow in October 2005. Medvedev, according to Rybachuk, was trying to influence Yushchenko through him. They even used the familiar “ty” form of address with each other. He asked Medvedev in his Kremlin office, which houses a goldfish aquarium, how it was possible that RosUkrEnergo was able to sell gas cheaper than market prices.

Medvedev seemed surprised:

“’Do you care? You must be happy?’ Medvedev said.

I said: ‘No I am suspicious, please explain to me.’ So I actually pushed him to that level where he says again on our side everything is transparent, blah blah blah.

Then he said: ‘This is a joint venture, 50 percent is yours.’

I said: ‘Whose?! Mine? Yushchenko’s?’

He said: ‘Yes, you are the power so it is yours.’

I tried to probe: ‘Ok so how much is ours? $500 million a quarter?’ Then he smiled. ‘So $2 billion a year U.S.?’: I said. He said: ‘Yes.’

‘And it is ours?’: I said.

‘Yes, it is yours.’ he said.”

Along with this news, Rybachuk returned to Kyiv with strong words from Putin that if “an understanding” wasn’t reached, gas supplies to Ukraine, and therefore Europe, would be cut in January 2006. Putin was threatening Yushchenko, who at the time was facing calls by the U.S. to end the use of controversial gas trading intermediaries.

Rybachuk was supposed call Medvedev directly from Kyiv with guarantees that RosUkrEnergo would continue to operate: “Then I would be allowed to really operate,” said Rybachuk, implying that he would get a share of the profits if he convinced Yushchenko.

“So I came back to Yushchenko, I remember, I will never forget that meeting. I said to him: ‘Now I know what is this. This is the way to corrupt any government in Ukraine because this is FSB operated scheme that is offshore, this is how they are making their own money and this is how they would like to corrupt us so I’m not going to call back Dmitry Medvedev. It’s clear for me that I cannot pursue this line.’ And Yushchenko was looking into the window and telling me nothing. He was not looking into my eyes.”

Kremlin spokespeople did not respond to request for comment.

Carpathian agreement

According to Rybachuk, he set about getting guarantees from the European Union and the U.S. State Department that Ukraine would not be forced into a deal if Russia cut off the gas. But when Russia did cut off the gas on Jan. 1, 2006, a meeting was held at Yushchenko’s summer house in the Carpathians to which Rybachuk was not invited and an agreement was reached that RosUkrEnergo would become the sole supplier.

No official record of the meeting at Yushchenko’s mountain summer house has ever been released but certain people were present who, they say, for legitimate reasons tried to convince Yushchenko into keeping RosUkrEnergo. One was Petro Yushchenko, his brother who introduced Firtash to the president, according to Rybachuk, and was himself involved in the gas business. The other was Hares Youssef, a Syrian businessman who has worked in Ukraine for over 20 years and is a close friend of Firtash and Yushchenko.

“I took Firtash by the hand when I was convincing Yushchenko to keep RosUkrEnergo. I personally convinced him because I knew Yulia (Tymoshenko) was behind the plans to get rid of it. I knew that she wanted to take the gas business and whom with. And if RosUkrEnergo was cut out the business then Ukraine would get gas for $50-70 more expensive,” said Youssef.

He told the Kyiv Post during an August interview that in return, Yushchenko asked Firtash to reveal his ownership of RosUkrEnergo.

Yushchenko declined to be interviewed for this story. With the 2006 gas agreement, Firtash became one of the world’s top gas traders. Moreover, his new status as a public figure entrusted with the number one state business of both elites also made him inescapable. He was rich, famous, powerful and entrenched in politics: he was now an oligarch.

Enemy No. 1

His success in Ukraine didn’t come without criticism. Leading the charge was then Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko. She knew the business all too well having made her own fortune through gas trading in the mid-to-late 1990s. Tymoshenko demanded an end to the use of intermediaries in the gas business and initiated an investigation into RosUkrEnergo, saying it was a corruption scheme.

Her ally, Oleksandr Turchynov, then head of the Security Service of Ukraine, began an investigation in June 2005. He told Ukrainska Pravda in July 2005 that he believed RosUkrEnergo was being controlled by Mogilevich with the consent of Yushchenko. In December that year, the SBU stopped their investigation into the intermediary. The state body then told journalists that such an investigation never existed. Turchynov told the Kyiv Post in a written response to questions in September that he was personally asked by Yushchenko to stop the investigation and subsequently resigned.

New deal

In late January 2008, Mogilevich was arrested in Moscow for alleged tax evasion involving Arbat Prestige. The arrest by 50 commandos, which took place in the capital’s financial district, was pertinently televised on Russia’s state channels. Mogilevich was later acquitted. His former lawyer, Gordon, told the Kyiv Post by phone in October that Mogilevich is still residing in Moscow and is not under any investigation.

The seemingly petty arrest of Mogilevich took place ahead of the February 2008 gas talks between then Prime Minister Tymoshenko and her counterpart Putin about a new deal. Naftogaz was heavily indebted to RosUkrEnergo, and therefore Gazprom and Russia were demanding payment. Tymoshenko told journalists in Brussels that the arrest signaled that the days of the “corrupt” intermediaries were numbered and hinted that the incident was directly connected to the talks. According to Warner, the arrest also signaled Putin would be the only one calling the shots.

Tymoshenko’s numerous visits to Moscow in 2008 couldn’t quite pull off a deal. On Jan. 1, 2009, Russia cut the gas with fatal consequences for many vulnerable people across Europe. In the deal reached during the crisis, Putin sold RosUkrEnergo down the river because Tymoshenko agreed to a price he “could only dream of,” Youssef told the Kyiv Post. It introduced direct supply between the two state companies for a price of $360 per 1,000 cubic meters.

Tymoshenko’s determination to get rid of Firtash was the force that arguably ended the political love affair between her and Yushchenko and any hopes that stood behind the Orange Revolution. It also did little to change Ukraine’s relationship with Russia. Immediately after the deal, Putin offered Ukraine a discount, says Victoriya Voytsitska, a deputy and the secretary of the parliamentary energy committee. “The contract was political. Putin could decrease the price according to loyalty of the Ukrainian authorities,” said Voytsitska.

In return, Firtash directed his efforts towards bringing Tymoshenko down in the 2010 presidential election by pouring money into the successful campaign of Viktor Yanukovych. Upon taking power, Yanukovych imprisoned Tymoshenko for the deal. Firtash’s close allies were put in charge of State Security Service of Ukraine, the Presidential Administration, the Energy Ministry and key positions at Naftogaz.

Yanukovych’s administration also failed to defend Naftogaz in a case against RosUkrEnergo for 11 billion cubic meters of gas Tymoshenko expropriated after taking on the company’s $1.7 billion gas debt. Naftogaz was forced to return the gas, worth $3 billion, and pay RosUkrEnergo $200 million.

Leonid and two Viktors

Firtash and his allies are “the most politically astute of the oligarchic groups,” according to Taras Kuzio, a British academic on Ukraine. Under each of the presidencies, Firtash’s two closest partners have repeatedly held strategically important positions.

Due to his family connections, Serhiy Lyovochkin was a presidential assistant to Kuchma when Firtash first started supplying gas, then assistant to Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych and finally his chief of staff after Yanukovych became president. Yuriy Boyko was head of Naftogaz in the early 2000s and twice energy minister. Together they managed to convince Kuchma, Yushchenko and Yanukovych of his indispensability.

When it was clear that Yanukovych was not going to survive the Euromaidan Revolution, “they saw the writing on the wall, according Kuzio, and Firtash’s self-declared “old friend,” Lyovochkin, resigned as Yanukovych’s chief of staff in January 2014. Firtash and Lyovochkin’s channel Inter, which is one of the most watched in Ukraine, subsequently switched its support to Petro Poroshenko, helping him secure the presidency in the 2014 election.

“They basically facilitated their post-Yanukovych life by ensuring Poroshenko came to power. That ensured that they were not on any Interpol watch lists,” said Kuzio. “Now it’s obviously a complete joke that if Yanukovych is crook and ‘mafioso’ that his chief of staff is not as well. Either his chief of staff is completely useless and didn’t know what was going on, or if he did know what was going on … he’s as guilty as his boss.”

Throughout the last decade, Firtash also cemented close ties with influential politicians across Europe. London, which he perceives as the “No. 1 financial center,” as he told The Wall Street Journal, has been the main focus.

With an uncertain situation in the Austrian courts because of the U.S., and Poroshenko seeming happy to have him out of the way, these foreign ties are arguably more important to Firtash.

EU sanctions

Just after the bloody end of the EuroMaidan Revolution, when dozens of protesters were shot dead in February 2014, Firtash met with British Foreign Office officials in London. Labor MP and treasurer of the All Party Parliamentary Group for Ukraine, Helen Goodman, made an official request for details about the nature of the meeting. The Foreign Office did not make public who was present and what was discussed.

David Cameron, then-British prime minister, has said several times that Britain was at the forefront of implementing the E.U. sanctions against Russia and Goodman believes, therefore, that the British Foreign Office is “very powerful for Firtash.” Despite Firtash being one of the main financers of Yanukovych, and Lyovochkin’s position as chief of staff, neither were placed on the sanctions list.

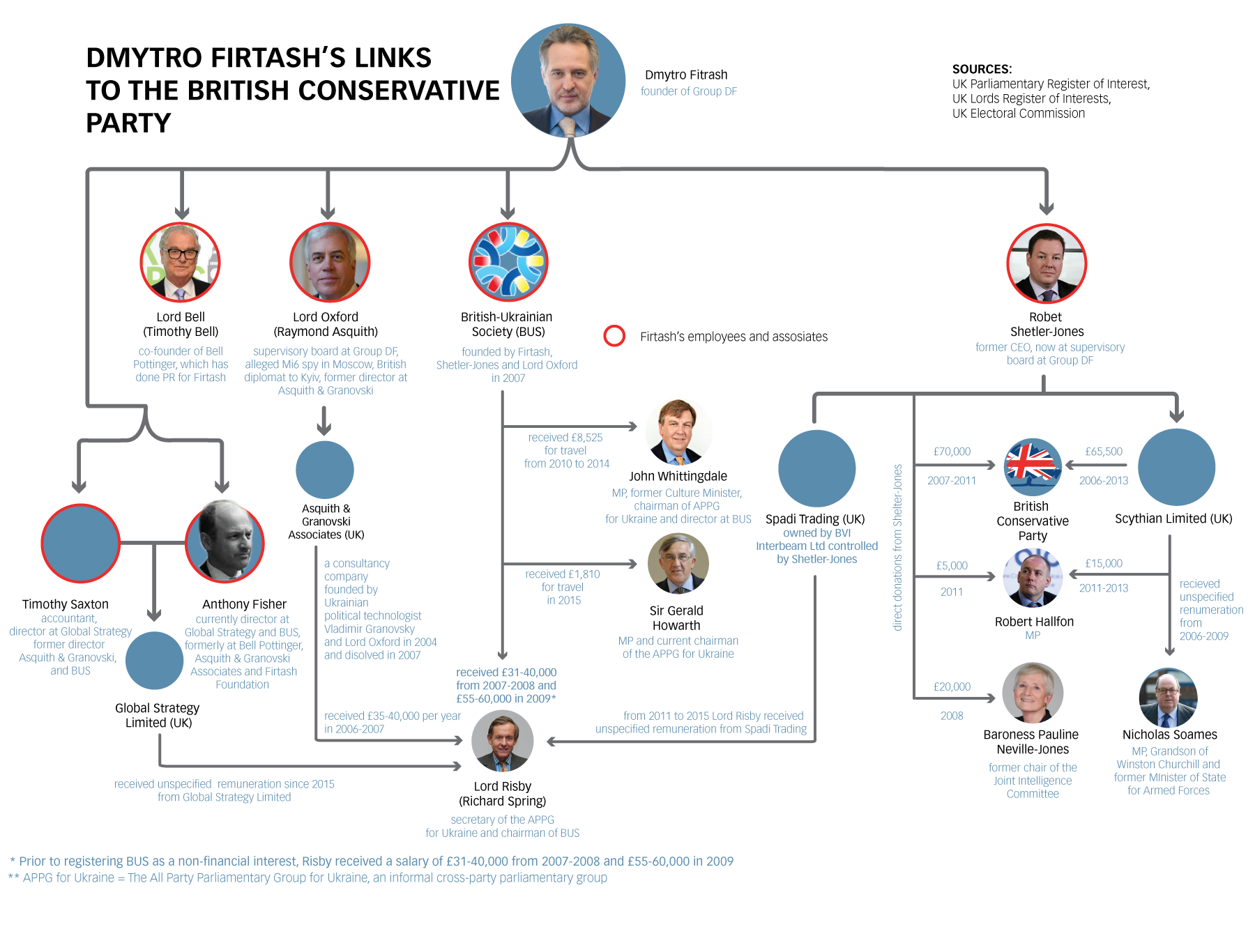

“It’s my contention, now I can’t prove this, that Firtash had access to the (British) Foreign Office, to officials, because he gave money to the Conservative party,” Goodman told the Kyiv Post. In total, the Conservative party, its MPs and Lords have received at least £300,000 from companies or individuals employed by Firtash, according to parliamentary and party donor registers (see British connections infographic below).

Parliamentary influence?

Perhaps the most contentious aspect of the payments is their recipients’ connections to the All Party Parliamentary Group for Ukraine. Their positions in the group make it difficult for them to deny that they are involved in parliamentary matters connected to Ukraine. The payments were highlighted by The Wall Street Journal in 2015, but the scandal didn’t deter some from continuing their association with Firtash.

In 2015, Lord Risby, secretary of the All Party Parliamentary Group and chairman of Firtash’s London-based British Ukrainian Society, stopped receiving money from Spadi Trading, according to his register of interests. Instead he noted a different company under his remuneration and paid employment section: British-registered Global Strategy Limited. Global Strategy is directed by Firtash’s employees ex-Bell Pottinger’s Antony Fisher and accountant Timothy Saxton (see British Connections graphic) and registered to the same address as the British Ukrainian Society. It has no website.

Neither the Lords Commissioner for Standards nor the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards has received any complaint or initiated any investigation into Firtash’s connections to the UK parliament.

The Kyiv Post made several attempts to contact Risby for an interview but received no response. In September, Risby attended the Yalta European Strategy conference in Kyiv, along with Tory MP Gerard Howarth, who is chairman of the All Party Parliamentary Group for Ukraine. Their trip was paid for by the British Ukrainian Society.

The Kyiv Post took the opportunity to ask Risby to describe the work he did for Global Strategy Limited. Risby responded by saying that he had “never heard it.” The Kyiv Post showed Risby his registered interests online to which he responded: “I don’t know what that (Global Strategy) is doing there … Thank you for pointing it out. I will have it removed.”

Risby was also asked about his work at the British Ukrainian Society and how its links to Firtash might be considered a conflict of interest with his work at the All Party Parliamentary Group. He said allegations that the idea that the British Ukrainian Society had anything to do with Firtash was “absolute rubbish.” This is despite Firtash telling The Wall Street Journal that he had founded the society together with Raymond Asquith, now known as Lord Oxford, and advisor Robert Shetler-Jones, also British, to “forge ties between politicians from the two countries” and “improve his reputation.”

Labor Lord Davis of Stamford, who is also an officer on the All Party Parliamentary Group but was unaware of payments, told the Kyiv Post: “As you’ve presented the facts to me, if these two colleagues were receiving payments from a Ukrainian oligarch while being chairman (officers) of the APPG then that is a scandalous state of affairs.”

Davis of Stamford also said that Risby is “more inclined to a pro-Russian viewpoint” but that they’d never had any detailed discussion.

Lord Risby (second from left) watches with Lada Firtash as Dmytro Firtash (R) and the UK House of Commons Speaker John Bercow shake hands during the opening of Firtash’s Days of Ukraine festival at the British parliament on Oct. 17, 2013.

Lord Risby (second from left) watches with Lada Firtash as Dmytro Firtash (R) and the UK House of Commons Speaker John Bercow shake hands during the opening of Firtash’s Days of Ukraine festival at the British parliament on Oct. 17, 2013.

British intelligence

Firtash’s money has also made its way to former and current British military intelligence figures. Lord Oxford, an alleged former MI6 spy in Soviet Moscow and ex-British diplomat to Ukraine is a member of the supervisory council at Firtash’s company, Group DF. Baroness Pauline Neville-Jones, chair of the joint intelligence committee (which advises the government using intelligence collected by the three British intelligence agencies), was blocked from receiving a promotion because she received £20,000 from Shetler-Jones. Firtash purchased a Ministry of Defense-owned London tube station for roughly £53 million in 2014.

Goodman also questioned the British government’s decision to accept money from Firtash for the tube station but said she received an unclear response. The British Ministry of Defense told the Kyiv Post that they were satisfied that all the necessary legal checks were carried out though they failed to detail the nature of those checks.

In August, 2016, the UK’s Channel 4 Tv station said it saw documents that Firtash paid only a third upfront, meaning the British taxpayer gave Firtash a loan of £33 million.

Shetler-Jones, the former CEO and now member of the supervisory council at Group DF, is credited with connecting Firtash to these levels of British society. He came to Kyiv in the late 1980s, according to him, to learn Russian – which he speaks perfectly by all accounts.

Phil Hudson, an architect and Kyiv property developer, employed Shetler-Jones in the mid-1990s to help with clients: “He was a young guy, looking to make money,” recalled Hudson. “I remember that after he left us, he was involved in property in Moscow. I met him maybe five or six years later in Arizona (restaurant). He didn’t want to talk. Then I received a phone call from Martin Harris, (general consul at the British Embassy to Ukraine at the time), he asked me about Robert (Shetler-Jones) and whether he came from money. Whether he would have enough money to buy a fertilizer plant. I said ‘No.’ It was only later it came out it (the plant) was owned by Group DF.”

“Either MI6 has penetrated Firtash or Firtash is penetrating them and it’s a cock up,” said Hudson.

Putin’s agent?

Firtash’s rise in Ukraine coincided with the expansion of Gazprom’s influence throughout Europe and many claimed that he was a “Putin agent” — hooking the Ukrainian elite, economy on low gas prices on Moscow’s behalf. As a Jamestown Report in 2009 titled ‘Gazprom’s Web’ illustrated, since Putin came to power, through other intermediaries Russia’s state gas company has influenced the elites of Hungary, the Czech Republic, Germany, and Italy.

According to Youssef, however, Firtash is no different to any other Ukrainian oligarch when it comes to his relationship with Moscow.

“Well I think if you look at the Ukrainian oligarchs, at all the big businessmen, not a single one of them would have been able to do big business in Ukraine without good and big contacts in Moscow,” said Hares.

This fact doesn’t erase the billions of dollars, (a Reuters investigation claimed as much as $11 billion,) Firtash received in financial backing from one of Putin’s closest allies, Arkady Rotenberg, as well as other Russian bankers close to Putin, without which Firtash would not have been able to rebuild his gas business, destroyed temporarily by Tymoshenko in 2009, and expand his business empire by buying up Ukraine’s fertilizer and titanium industry. No other Ukrainian oligarch has received loans of such size from Russia.

Russian billionaire Vasily Anisimov, a business partner of Rotenberg, also posted a record $174 million in bail for Firtash in Vienna.

But according to Youssef, Firtash is a “Ukrainian patriot,” and has invested his profits back into Ukraine:

“For Russia, Firtash was a bad and unprofitable partner because Firtash was representing the interests of Ukraine. He took the interests of Ukraine in his own hands. And helped Ukraine more than Russia. In 2005, 2006 and 2007, before Yulia (Tymoshenko) interfered.”

Acquiring total control

Under Yanukovych, Firtash and his partners’ control over Ukraine’s gas sector went from majority to total, according to Yuriy Vitrenko, chief adviser at Naftogaz, who has worked in top positions on and off at the company since 2002.

Through Boyko’s “vertical” as minister of energy, they appointed their allies to all the top positions in Naftogaz and at the Naftogaz subsidiaries Ukrtransgaz and Ukrgazvydobuvaniya, gas transit and production monopolies. At the same time Firtash’s “vertical” bought up a series of regional gas distribution companies. They were able to control both the state and private sector, Vitrenko told the Kyiv Post.

In 2013, the year the EuroMaidan Revolution started, businessman Serhiy Kurchenko, one Yanukovych’s closest allies and known by the press as part of the “family,” came into conflict with the Firtash’s gas group. Ukrainska Pravda reported that Kurchenko started to place his people on the board at Naftogaz in order to further aid his gas import scheme. Reuters reported in 2014 that Firtash’s Ostchem used to sell Kurchenko cheap Russian gas, which Kurchenko would sell on at market prices. It was Firtash’s way of rewarding Yanukovych, said Reuters’ sources.

By this time, the greed of Yanukovych’s family was getting so out of control that some believe a pact among oligarchs was reached to undermine the president, yet keep the oligarchic system in place. In this environment, Lyovochkin appeared to serve as a moderator balancing the interests of Yanukovych, Kuchma and his son-in-law, Victor Pinchuk (from his days at Kuchma’s administration) and that of his friend and business associate Firtash.

Revolution disrupts

In November, Interior Minister Arsen Avakov accused Lyovochkin, who was then head of Yanukovych’s administration, of ordering the beating of students on Nov. 30, 2013: “His place is in jail not parliament.” Avakov hinted that Lyovochkin ordered the beatings in order to increase public anger towards Yanukovych.

Lyovochkin has denied the accusations, saying the beatings were the reason he resigned. But Yanukovych rejected his resignation, and Lyovochkin stayed on until Jan. 17.

Artem Shevchenko, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Interior, told the Kyiv Post that this was “Avakov’s political position,” and that only the National Anti-Corruption Bureau had the right to investigate parliamentary deputies such as Lyovochkin.

The violence perpetrated against the students by Ukraine’s riot police is seen as the turning point in the protest movement. The following day hundreds of thousands of people took to Kyiv’s streets.

Yanukovych, ex-Interior Minister Vitaliy Zakharchenko and former Kyiv Police Chief Valery Koryak (all three are currently in exile in Russia) have also accused Lyovochkin of being behind the beatings. Most recently for a trial on the Maidan protests via video link from exile in Russia, Yanukovych retracted his initial accusations. He said of the beatings on Nov. 28:

“Yes, maybe he (Lyovochkin) had something to do with it. But I personally have no evidence of this, and evidence has not been established. Therefore, if it was so, then the authorities should prove it, if they don’t prove it, let it be on his conscience. Or if he is innocent, then let those who say such things should apologize, it should be established by the court,” Yanukovych said.

Investigative journalist turned parliament deputy, Sergii Leshchenko, who has seen orders and protocols written by Yanukovych cronies during the EuroMaidan Revolution said that he hadn’t seen one signed by Lyovochkin.

Others believe that Oleksandr Yanukovych, the president’s older son, was behind the crackdown but that Lyovochkin must have known about it.

Via video link Yanukovych also accused Firtash and Lyovochkin of plotting to bring down the Party of Regions and “destabilize” the country. Analysts have pointed to the fact that his speech must have been pre-approved by the Kremlin, and is a direct sign of their discontent with the Firtash group.

The Naftogaz divorce

The Firtash clan’s world, just like for Yanukovych, broke down because of the EuroMaidan Revolution.

The main strategy of the post-revolutionary government of Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk was to get rid of Gazprom’s influence in Ukraine and stop the reliance on Russian gas, according to former journalist and now People’s Front deputy Serhiy Vysotsky. Ukraine stopped buying Russian gas directly in April 2014. At the time, the presidential executive and the government were controlled by People’s Front politicians: then Acting President Turchynov, Prime Minister Yatsenyuk and Interior Minister Avakov.

“They went after Firtash very much. They started to prosecute Firtash. To prosecute Yevhen Bakulin (former Naftogaz CEO, now Opposition Bloc deputy and Boyko’s friend),” said Vysotsky.

Most of Firtash’s allies in charge of Naftogaz and its subsidiaries fled, according to Vitrenko. The new management at Naftogaz proceeded to fire dozens of people at the very top, said Vitrenko, though their control is not yet total. At Ukrtransgaz, three of the top managers, who were managers at Firtash companies, currently head the company.

“Since this group controlled the whole gas sector for years, it’s at least reasonable to expect that they still have a lot of people who worked with them and there are some strings attached from these people to the Firtash group,” said Vitrenko.

Inter’s influence

Yatsenyuk’s party and government also went after Firtash’s television channel Inter, among Ukraine’s most watched. In February 2015, they pushed for a law banning Russian ownership in Ukrainian media assets. Until then, Inter was officially 29 percent owned by the Russian state channel, First Channel, who divested their shares to Group DF, according to a Group DF statement. Group DF’s director Borys Krasnyansky said at the time that the Russian owners had no influence over management.

“We consider it a fake sale. We consider there was no real sale of Russian interests in the channel. We see it (their interest) through the management of the channel, the channel’s agenda,” says Vysotsky, referring to the two Russian journalists who called the post-Maidan authorities “junta” and “fascists” before becoming managers at the channel. One has since been deported to Russia by the Ukrainian authorities. In response, according to Vysotsky, Firtash started to attack People’s Front using Inter.

Nataliya Ligacheva, director of media monitoring group Media Detector, says that the channel’s content is “completely thought out.” According to her, People’s Front is the only group Inter attacks: “It used to be Yatsenyuk, Yatsenyuk and now it’s Avakov every day.”

In September, the animosity appeared to cumulate in a fire at Inter’s second TV studios. Firtash said that Avakov personally ordered the fire to shutdown “freedom of speech” in an interview with RBC Ukraine in October. Avakov has said that the fire was staged and called the channel a pro-Moscow mouthpiece.

“He puts Yanukovych employees on the news and makes them appear wonderful: ‘They can reunite the country…We need peace…Our government is incompetent.’ They don’t say anything about the war and Russian aggression in Ukraine. They all say we need peace and the Opposition Bloc (the party which Firtash’s group supports, along with oligarch Rinat Akhmetov) will give you peace. They are creating disillusionment among Ukrainian citizens. This is one of the key Russian strategies – to spread disillusionment,” said Vysotsky.

While they never praise Putin, they avoid criticizing him and mentioning Russia’s involvement in the war, says Ligacheva. “They are maybe not direct agents of the FSB, with hats and big glasses, but they robbed Ukraine in favor of Russia,” said Vysotsky.

The Kyiv Post asked Lyovochkin about the accusations against Inter at an art exhibition in Kyiv. He said: “Inter is 100 percent pro-Ukrainian. We have millions of viewers and we are very grateful for that.”

Interestingly, according to Ligacheva, the channel this year has given favorable coverage to Tymoshenko and her Fatherland party. According to several deputies the Kyiv Post spoke with, they perceive Tymoshenko to be in a situational alliance with Firtash as she is also pushing for early elections. Despite her long running history with Firtash, Tymoshenko refused to comment on “the past” for this story.

“It’s not like Putin calls Lyovochkin or Tymoshenko and says directly you must do ‘xyz’,” said Vystotsky. “But by the nature of their destabilizing actions, they are empowering Putin’s plan in Ukraine.”

Ukraine and partners

An Austrian judge ruled in April 2015 that the U.S. extradition request for Firtash was politically motivated and he is now awaiting the result of the U.S. appeal. The judge said the U.S. failed to present key witnesses and pointed to the fact that the U.S. had rescinded a request in October 2013 after receiving assurances from Yanukovych that he would sign the EU Agreement.

Emails from the FBI to the Austrian authorities seen by The Guardian in 2016 support the theory that the arrest was politically motivated. According to The Guardian, the U.S. was trying to get Firtash out the way in order to allow for the creation of a pro-European government.

According to Youssef, the U.S. arrested Firtash on request of the Ukrainian government in order to take full control over the economic resources of the country and reassign his property: “Dima didn’t fit with the interests of the new team…It was advantageous for everyone.”

Another rumored advantage for the US is the potential information on Russia’s elite that they may be able to extract from Firtash.

In interviews that echo the Kremlin line, Firtash has said that the current authorities have brought the country to the edge of catastrophe and that the U.S. is governing Ukraine from abroad. He has also said that his businesses are being dismantled by the authorities in his absence.

Since the EuroMaidan Revolution, aside from losing most of his control over the state gas sector, Firtash’s bank Nadra was declared insolvent, he was removed from his position at the Federation of Employers Association, his titanium plant in Crimea has been (along with other businesses) sanctioned by Ukraine, a court took 95 hectors of allegedly illegally sold forest from Group DF and he has been forced to pay millions of dollars to Naftogaz for his fertilizer companies.

There is also a question of whether he will hold onto his regional gas distribution companies and tacit control over Ukrtransgaz. Parliamentary energy committee Secretary Voytsitska says that a shakeup of the sector is required to fully implement the new gas market law which includes installing meters for consumers to reduce costs.

“The current status quo allows the regional distribution companies to continue unchecked and almost without control to use the state gas networks,” said Voytsitska.

However, at present, Firtash, according to Vitrenko, is resisting the changes.

Voytsitska also doesn’t see this happening in the near future.

Vitrenko said of Firtash’s claims that his businesses were being attacked by the current authorities: “The real question is whether this is good or bad. If your whole business model is basically something really dodgy and really bad in terms or law, fairness, competition then going after those business interests is probably the right thing to do.”

‘Vienna Pact’ alive

Firtash remains a top 10 oligarch and his fellow oligarchs could argue they’ve been hit worse in the last two years.

“There haven’t been attacks on Firtash’s businesses in the same way as (oligarch Ihor) Kolomoisky,” said Leshchenko, referring to Poroshenko’s push to get rid of Kolomoisky’s alleged rent-seeking at majority state-owned oil producer Ukrnafta.

“The Vienna Pact is still working,” said Leshchenko, referring to a meeting among Firtash, President Petro Poroshenko and boxer politician Vitali Klitschko in Vienna just after he posted bail in March 2014. The alleged deal saw Firtash pledge support for Poroshenko in the elections on Inter, in exchange it seems for freedom from prosecution for his allies: Boyko and Lyovochkin.

Firtash told the court in Vienna that he convinced Klitschko to stand down in the presidential elections to clear the way for Poroshenko. Poroshenko and Klitschko deny any deal was made.

Inter continues to present Poroshenko with neutrality, said Ligacheva. The channel is also the most popular channel in the east of the country, according to Ligacheva, because of its majority Russian -language content — this viewership is very important for Poroshenko. Poroshenko also relies on the Opposition Bloc, where Boyko’s and Lyovochkin’s opinions are very powerful, says Leshchenko. The current ruling coalition is so fractious that their deputies can sink or turn votes in parliament.

“They were very successful in reinventing themselves,” said Kuzio. “And now they control half of Opposition Bloc.”

A Firtash return?

Firtash has repeatedly stated his intention to return to Ukraine and said that he will seek to influence events in the country. That’s unless the Austrian judges decide to send him to Chicago to face trial or he isn’t extradited to face trial in Spain for money laundering. Spain filed extradition papers with Austria on Nov. 30. If the Austrian court finds no circumstances which contradict the Spanish extradition request, it will go to trial. This could mean another few years in Austria and potentially a lengthy trial in Spain.

The Ukrainian authorities have issued mixed messages regarding whether they would arrest him if he returned to Ukraine.

A spokesman for the Interior Ministry, Artem Shevchenko, told the Kyiv Post that last year Ukraine said it would cooperate with its Western “partners” in handing Firtash over to the FBI for trial.

However, the ministry might revise its position depending on the outcome of Firtash’s appeal, said Shevchenko. He also said that there are several ongoing criminal investigations into companies where Firtash had alleged interests or is a current shareholder, such as UkrTelecom and Ostchem. “There are lots of people who want to talk to Firtash,” said Shevchenko.

If he was allowed back he would arguably need to once again prove his worth to Russia as a power broker in order to regain his position.

But his fertilizer plants are no longer buying Russian gas, indicating perhaps that he is no longer treated to preferential prices after losing much of his control over the sector.

And his loyalty to the Kremlin has been questioned by Russia’s top circles. In an interview with Firtash, without naming names, Bloomberg reporter Ryan Chilcote said that his Russian partners believe the U.S. agreed not to extradite Firtash in exchange for information on the workings of Gazprom and Rotenberg. Firtash denied this saying he has never met with the FBI: “I did not tell anyone anything, because I have nothing to tell.”

Vitrenko believes that it would also be difficult for Firtash to undo improvements made at Naftogaz.

“Although he’s not here, his businesses are here, his managers are here. They fly to Vienna every week to get instructions from him so I can’t see any big change,” said Vitrenko.

From the comfort of Vienna, however, Firtash appears unfazed by the threat of arrest by Ukrainian officials. Asked in October if he was afraid to return home, he told RBC Ukraine: “They should be afraid of me.”

For now, Firtash’s fate lies in the hands of Austrian judiciary. Ukraine could be one oligarch down.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter