It sounds like quite a problem, but Igor Pasternak thinks he has the answer. He invented a lighter-than-air cargo transporter called an aeroscraft.

The 52-year-old Pasternak heads a company, Worldwide Aeros Corp., that has been developing such aircraft since 1986 – first in Soviet Ukraine, and then, after relocating in 1994, in the United States.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

The development of his first aeroscraft cargo transporter, called the Dragon Dream, was financed by the U.S. Department of Defense.

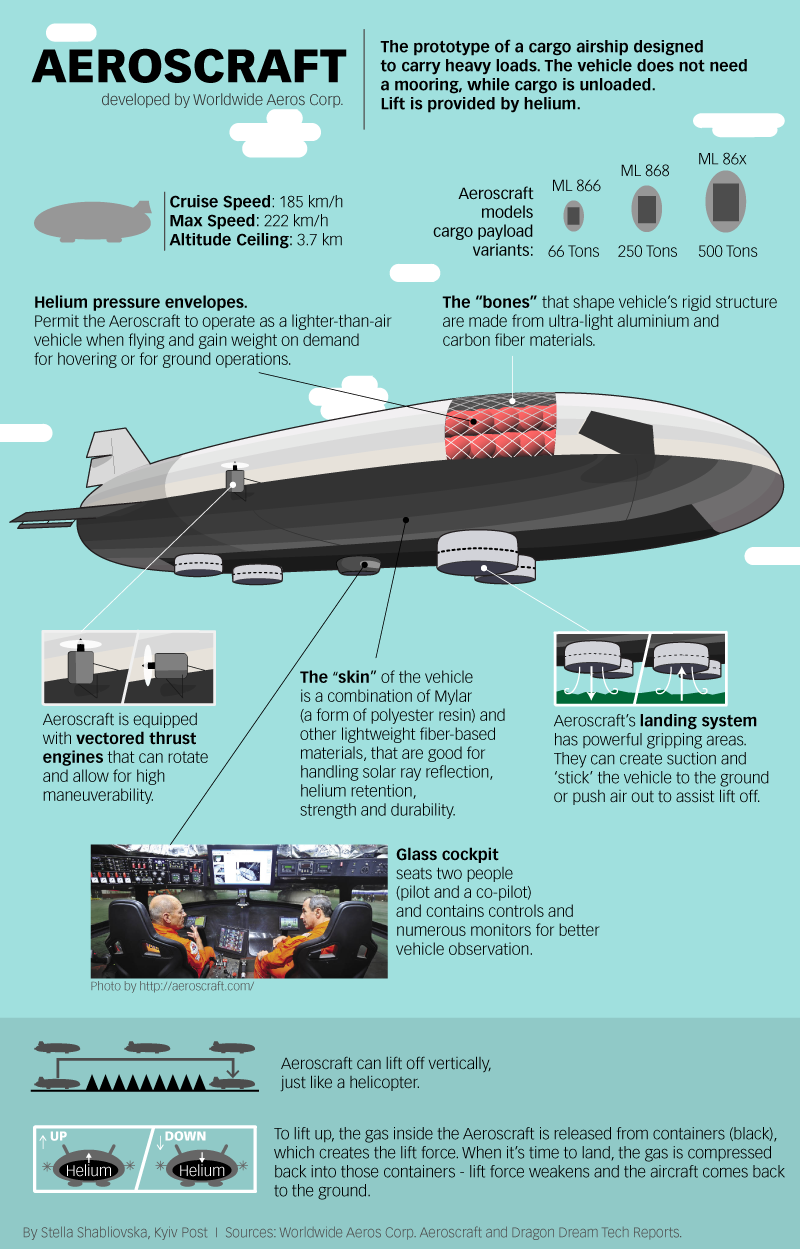

The 81-meter-long and 30-meter-wide prototype was built in 2013, and it’s only the smallest cargo vehicle proposed by Pasternak. In the future, he plans to build it in four sizes. The biggest, the ML86X, will be about 280 meters long and able to carry 500 tons in its internal cargo hold.

Submarine of the sky

But what would stop a lighter-than-air aeroscraft shooting straight up into the sky after unloading a cargo equal to the weight of 150 elephants?

In the past, such vehicles have had to vent their buoyancy gas (usually helium, which is expensive) when landing, and use external ballast, such as rocks, water, or lead bags, as well as landing infrastructure such as mooring cables and towers, to hold them in place when offloading cargo or passengers.

The aeroscraft needs none of that. It can even hover in place, without touching down, and deliver a cargo to the ground, winched down from its cargo hold.

It achieves that through an innovative buoyancy control system similar to the ballast systems submarines use.

To reduce buoyancy, it pumps helium out of its lift bags into compressed helium tanks, with air being sucked in to fill the void left as the helium lift bags deflate. Air being heavier than helium, this reduces the aircraft’s buoyancy. To increase buoyancy, the helium lift bags are inflated again, pushing the heavy air out of the aircraft’s body, and making the vehicle lighter again.

The aeroscraft is equipped with six multidirectional turbofan engines that allow the aircraft to hover, maneuver, and propel the Dragon Dream to flight speeds of up to 60 knots, or 111 kilometers per hour. Future models should be able to travel at up to 185 kilometers per hour.

The Dragon Dream is the only vehicle of its type built so far, but Pasternak hopes to produce thousands after the aeroscraft is fully certified by the U.S. aviation authorities.

Coming to America

As a 17-year-old student, Pasternak founded an airship design bureau at Lviv Polytechnic University. Following the perestroika reforms, he set up one of the Soviet Union’s first private aerospace companies, Aeros, in 1986, and a year later he got his first order – to make an aerostat for the Lviv City Day celebrations.

Although trained in civil engineering rather than aircraft design, Pasternak focused on this business. Aeros started to make tethered aerostats, mainly for advertising purposes, and sell its products in the Soviet republics and even further afield.

But then came the collapse of the Soviet Union, and in the ensuing economic turmoil, sales dried up, and manufacturing materials became hard to find.

So in 1994, Pasternak packed his possessions – consisting mostly of technical books crammed into two pieces of luggage – and moved to the U.S. with two colleagues.

Igor Pasternak. Citizenship: U.S., former Soviet;

Age: 52;

Profession: Airship designer and builder

How to succeed in Ukraine: “Ukrainians can follow the US model where the American dreams exists. Just grab the idea of the American dream and call it the Ukrainian dream”

When he got to the U.S., he had almost no money, no connections in the business world, and, furthermore, no English language knowledge.

“I had absolutely zero English skills,” Pasternak recalls. “The only things I knew about the U.S. came from the Hollywood movies.”

But he and his colleagues had dreams of building airships, and the knowledge of how to do it. Reestablishing the company in the U.S. wasn’t easy.

“But when you don’t know the challenges you’re going to be faced with, you don’t take them as challenges,” he says.

When the dollars Pasternak brought from the Soviet Ukraine ran out, he secured a bank loan.

“We were just crazy enough to ask, and people really thought we knew what we were doing, so they lent us the money,” he said.

Today, Pasternak’s Worldwide Aeros Corp. employs around 100 workers in Montebello, California. The company has a $15 million annual turnover (according to Ukrainian online newspaper Forbes), and produces airships for countries all around the world.

Its clients include the U.S. Army, MasterCard, Germany’s Commerzbank, and dozens of private companies. Since the EuroMaidan Revolution the company has worked with the Ukrainian Defense Ministry and has opened a subsidiary in Ukraine – Aeros Ukraine Ltd.

From advertising to the military

Pasternak started producing blimps in the United States for use by broadcasters and advertisers, and his company’s initial successes were built on that business. But that changed after the 9/11 attacks in New York.

Almost overnight, Worldwide Aeros Corp. went from making advertising blimps to making surveillance blimps. The company became a contractor of the U.S. government, manufacturing surveillance aerostats to monitor airports, border areas, and oil pipelines.

“The government recognized the huge capabilities of the technology we’re producing,” Pasternak says about his company’s work with the U.S. government.

Worldwide Aeros Corp. now dominates the market of surveillance blimps, he said.

The Sky Dragon airship remains the best-selling vehicle Aeros has designed. The latest version, the Sky Dragon 40E, can travel more than 500 kilometers, conduct 24-hour non-stop monitoring and imaging, and observe up to 70,000 square kilometers.

But for Pasternak, a successful company is not enough. His next challenge is to revolutionize the delivery of cargo by air with his aeroscraft.

“It’s kind of a new type of air vehicle. It is a little revolution in logistics,” Pasternak says.

Being Ukrainian

After Pasternak moved to the U.S. in 1994 and before 2014, Pasternak returned to Ukraine only once for a weekend. Then the EuroMaidan Revolution in Ukraine occurred, and 20 years after he first left the country, Pasternak returned to Ukraine again.

In February 2014, after the security forces of ex-President Viktor Yanukovych shot dead around 100 EuroMaidan protesters, Pasternak found himself walking on Kyiv’s central square, Maidan Nezalezhnosti, where the central protest camp was based.

“(At that moment) I understood that I am a Ukrainian,” Pasternak said during an interview on Ukrainian television’s Espreso TV shown on April 2015.

Before seeing the EuroMaidan protests, he identified as an American.

Pasternak then started to visit Ukraine every month or two. In January, he signed a contract for Aeros to supply Ukraine’s State Border Service with a surveillance system to monitor the Sea of Azov.

He suggests business people in Ukraine start thinking globally, as he did two decades ago.

“Ukraine can follow the European model, where there is no innovation, where everything has become slow and standardized, or Ukraine can follow the U.S. model, where the American dream exists. Just grab the idea of the American dream and call it the Ukrainian dream,” he jokes, adding more seriously: “If you believe in your vision, you can change the world.”

Watch “The Blimp-Maker,” a video by The New Yorker telling the story of airship maker Igor Pasternak, here:

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter