Prolific artist, musician, composer, and singer Roman Turovsky was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, and emigrated to New York with his family at 18. The son of prominent artist Mikhail Turovsky, Roman was immersed in the art world since he was a child in the former Soviet Union. He came into his own in the West, a combination that undoubtedly influenced his artistic endeavors.

Turovsky made his mark in the film and television industry as a scenic artist on very successful American shows such as ‘Law & Order,’ ‘Law & Order: Organized Crime,’ ‘NYPD Blue,’ ‘Quantico,’ and ‘Narcos,’ among others. He has worked for renowned filmmakers Stephen Daldry (‘The Hours’), Darren Aronofsky (‘Requiem for a Dream’), and James Mangold (‘Cop Land’), to name a few.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Roman spoke to Kyiv Post about all of his artistic endeavors, as well as his thoughts and opinions about Russia’s current war with Ukraine.

Tell me about your job as a scenic artist in the film and television industry. What does that entail?

Scenic artists execute the ideas that production designers or art directors give them in set construction. We are responsible for the final finished surfaces, including colors, textures, and, most importantly, aging. The camera does not like anything that looks new – it reads as unnatural – so we make things look like they’ve been lived-in.

Ukrainian Musical Breakthrough

What are some examples of these set items?

It can be anything from objects handled by actors, parts of set dressing such as light switches and walls, or even whole rooms. For example, maybe an apartment has to look 50 years old, and during those 50 years, it has been painted three times by three different owners. We have to ensure all that is conveyed in the final look of the apartment. Usually, we receive specific instructions on how old an object has to look or references such as photographs we then reproduce.

Can you give some examples?

On ‘Law & Order’ season 21, we had to reproduce the sets from the original show because the original sets were no longer usable. They were produced in the ‘90s before high-definition television, so we had to recreate them with much greater refinement and detail. The old sets looked quite theatrical by comparison because the camera equipment back then was very different from what they use now.

What are some of those set pieces from the show?

There were four main sets from the original “Law & Order” that we had to remake from scratch. We completely recreated the courthouse, the squad room, the police precinct, and the prosecutor’s office. It involved a lot of faux marble. The original sets were made with faux woodgrain, but they could not be used anymore because the HD cameras could pick up too many imperfections. We had to use real wood, real stain, and real varnish.

In your career as a scenic artist, do you have any favorite jobs that stand out?

The job I’m most proud of is one I did in 1998 for Jim Jarmusch on ”Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai.” Jarmusch is an amazing director. Not only that, but he’s also a real artist and a real gentleman. We had the task of building a boat on a rooftop which was very unusual. Most of my job was on the set aging various objects. I had to make things look old so they would look good on camera.

You also worked on David Bowie’s last music video, ‘Blackstar.’

That was my second proudest job. It was more than a music video: It was like a short film. Three-quarters of it was produced in Bucharest, Romania. I was in charge of the scenery on the New York part of that job. We had to create a house with a broken roof through which the light flows. At the time, Bowie already knew he was dying but we had absolutely no idea.

How did you get into scenic artistry?

I’ve always wanted to be an artist and I studied art for a very long time. Unfortunately, it isn’t easy to support oneself in that field, so I had different jobs. I worked in advertising as an art director when I got out of college. Then I worked as a social worker in refugee resettlement because I’m quadrilingual: I speak Ukrainian, Russian, English, and Italian. It was quite useful because there was a huge influx of ex-Soviets in the late ‘80s, and early ‘90s. A coworker said I should consider being an artist in the film industry because the schedule was irregular, the money was good, and I could have a lot more time for myself and my art. So I took the exam for the scenic artists’ union. It took me three tries to get in, and I finally did in 1993.

You were born in Kyiv and emigrated to the U.S. in 1979 when you were just 18 years old. What made your family leave the Soviet Union?

One of the most significant factors was the looming army service because it was the beginning of the Soviet debacle in Afghanistan. The conscription was a huge risk. Also, my father was an artist and he was at odds with the authorities. He wasn’t getting any work or commissions, so my parents realized we had to leave the country.

Was that a complex process?

Yes and no. In the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, the Soviet Union was forced to liberalize the emigration policy. At the time, it had a grain shortage and two American politicians advanced what was called the Jackson-Vanik Amendment, permitting the United States to sell grain to the Soviet Union in exchange for liberalization of emigration policies. However, any young person leaving the Soviet Union was required to be expelled from their colleges or schools. I had to be expelled from high school and, at the time, I attended an elite art high school in Kyiv. The Soviets purposely made it as humiliating as possible to leave.

When you got to the U.S., how did you feel?

I was mesmerized by this country. I had one year of high school in the Bronx. They gave me an English test and said I had the English proficiency of a 12-year-old, which was the best they’d seen in an immigrant kid. Afterward, I went to Parsons School of Design, where I studied art. I also developed a side interest in music and studied that as well.

When did your Ukrainian culture begin seeping into your work as an artist?

I was studying the music of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, which has no connection with Ukrainian music. I realized that if I combined Ukrainian music with the musical technology of Renaissance and Baroque, the result could be quite unusual and interesting.

What kind of Ukrainian music did you combine it with?

My mother’s family is from a village 100 miles west of Chernobyl in the northern part of Ukraine. One of my earliest memories was of evenings in the village on the Desna River. There were boats full of girls rowing to the other side of the river to a meadow where they would milk the cows. They would sing in their boats. The songs were traditional Ukrainian polyphonic songs from the Polissia region: That never left my memory. I was probably two or three years old, but I still remember it. I took those tunes, and I started writing Renaissance-style variations.

How did people receive that?

I was doing this without any consideration for the Ukrainian audience. It was designed purely for a western audience, and many didn’t even know where Ukraine was on the map. I released three full-length CDs of material, that are commercially available. The most amazing development was that my work became popular in music circles, and musicians across the world started to perform them.

Then I began composing for films, including a documentary called ‘She Paid the Ultimate Price’ by a Ukrainian filmmaker in Toronto, Iryna Korpan. It was about her grandmother, who was hanged by Germans for hiding a Jewish family in her cellar.

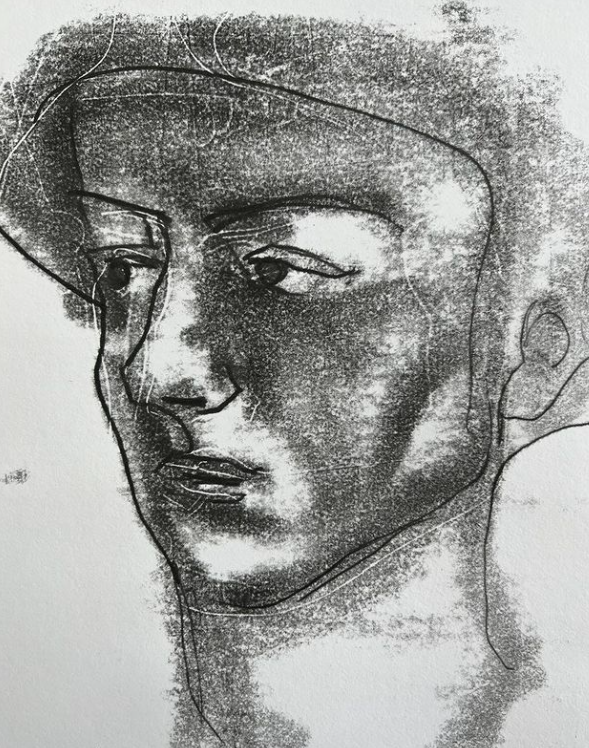

Throughout your careers, you have managed to thrive as an artist, had solo shows in New York in 2005 and 2013, and will soon release a new collection of art based on a form called monoprint. Tell us about that.

During the pandemic, when many film projects were put on hold, I had a lot of free time and began focusing on monoprints. I have done over 600 pieces that are not publicly available yet but I have posted many of them on Instagram (@roman_turovsky).

As if all your art and music were not enough, you also sing.

I am a great fan of our traditional Ukrainian melancholic music. I think it’s one of the most significant cultural achievements of the world. In 2002 I met Julian Kytasty, who is probably the greatest Ukrainian folk musician in the western hemisphere. We did a concert titled “Songs of Murder, Mayhem, and Treachery: A Musical Exorcism.” It was incredibly beautiful, and it’s completely apotropaic – which is a belief that by enacting an atrocity on stage, it would prevent it from happening in real life. That is the ideology behind it.

That concert was fantastic. People went nuts over it. We did a whole series of them. I’ve accompanied Julian’s singing quite a bit over the years and we have given quite a few concerts at the Ukrainian Museum and the Ukrainian Institute in New York. Another notable concert we did in 2005 was devoted to the soldiers’ songs from Ukraine, divided between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires and forced into fratricide.

How is the current state of your homeland affecting you today?

Being Ukrainian and seeing history repeating itself for the 120th time drives me nuts. I do everything I can to support the Ukrainian war effort monetarily and otherwise. I recently sent military-grade first aid packs to Ukraine.

A classmate of mine is in the army now. I have some extended family in Melitopol, which is now occupied, and since that invasion happened, we have had no contact with them. We have no idea what’s going on there.

What does Ukraine need from the rest of the world right now?

One of the key aspects of the Russian people is that they physically cannot improve their lives. They think the only way to improve their lives is by destroying the lives of their neighbors so their own will look better. Right now, Ukraine needs every imaginable help: both armaments and financial help. What we need is a victory. Nothing else would work. A compromise is not in the cards because the other side is unwilling to concede anything.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter