The name of Gareth Jones, the journalist who exposed the Ukrainian famine of 1932-33, also known as the Holodomor, in which millions of people died, is well known in Ukraine. Not only does he have a street named after him in Kyiv, but he was also posthumously made a Hero of Ukraine by the Ukrainian government.

However, the Welshman from the coastal town of Barry, has not received the wider recognition he deserves in his own country. Until now.

Martin Shipton, Political Editor-at-Large of the Western Mail, a newspaper that Gareth Jones worked on as a reporter, has just published a biography about him.

Called Mr Jones, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Shipton, said: “The family had written materials themselves, but what was needed was a fresh and more contemporary look at Gareth Jones.”

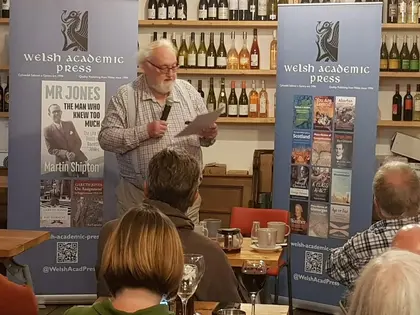

Following a busy book launch at the Little Man Coffee Shop in Bridge Street, on Monday, September 5, the name Gareth Jones was again heard in Cardiff, with its author highlighting the tremendous achievements of this investigative journalist, who never made it to his 30th birthday.

Members of the diaspora sat and listened in awe, joined by the new arrivals from war-torn Ukraine. Mick Antoniw, MS (Member of the Senedd – Welsh Parliament) is the Legal Council of Wales and a member of the Welsh Government Cabinet, who wrote the foreword to the book, spoke passionately about his family back home, and said Ukraine would never yield to Vladimir Putin, who he described as a fascist.

Before the book launch, author Martin Shipton spoke to Kyiv Post.

The book’s publication was delayed by COVID and Martin being seriously ill – but the negative aspect of this worked in favour of making the book more timely and relevant.

“With Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, there were so many resonances with the way Ukraine had been treated in the 1930s in the context of the Holodomor,” he said.

“In a way the delays made it possible for me to make much-more telling observations and comparisons between what was going on in the 1930s and what is happening today.

“It gave the book an extra dimension, and also the other factor that led the book to be written was that there had been a film produced about Gareth Jones [released in 2019].”

I asked Shipton whether his desk at the Western Mail was anywhere near to where Gareth Jones would have sat. It had been portrayed in the film starring James Norton. Unfortunately, Shipton said, the office had been mocked up.

The original newsroom where Gareth would have knocked out his stories on a typewriter had long gone. A new building had gone up in 1961 which was decades after he had passed away, and the latest office was built in 2008.

The only crumb of comfort that Shipton could give me was that the original building where he would have filed his stories was a few hundred metres away in the centre of Cardiff.

And as if it mattered, he said: “He lived in Barry which was about 10 miles away, which meant he had to get the bus to work.”

The 348-page book is an easy read, peppered with lots of archive material which Shipton waded through during weekends and evenings while he kept up his day job. There were overnight stays in Aberystwyth, where The National Library of Wales is based. There he faced a mountain of letters and other materials.

“When he was on his travels he would write at least a weekly letter to his parents,” said Shipton. “There were also notebooks that he had.”

It took Shipton about three years to write, but what stood out the most about the book for him was to see the development of Gareth Jones into somebody who could stand up to a very powerful group of journalists who were basically monopolising what was going on in the Soviet Union.

“I wanted to understand what it was from his past that gave Gareth Jones the tools and strength of character to be able to take on these very powerful interests,” said Shipton.

“It was his whole history of someone who had come from a family in Wales, where both of his parents were very principled individuals. His father was a headteacher of a local school, his mother had worked in Ukraine as a nanny to children of the John Hughes family, who went from Merthyr Tydfil, and established an iron works in what is now Donetsk [formerly called Hughesovka].

“His parent were Liberals and with Gareth working for the great statesman David Lloyd George gave him a lot of self-confidence,” said Shipton.

In the book, people from the West, like playwright, literary critic and prominent British socialist George Bernard Shaw, were taken in by the Soviet regime. Although a big voice for the underdog, Shaw believed he had found the ‘worker’s paradise’.

Gareth Jones was also up against Walter Duranty, the New York Times bureau chief in Moscow, dubbed Stalin’s apologist, who said Jones had based his Holodomor views on a large-scale famine by visiting a small area of Ukraine.

In response, Jones said his evidence came from three trips to Russia, visiting 20 villages in Ukraine and what was termed the ‘black earth (chornozem) district’ and speaking to 20 to 30 consuls and diplomatic representatives of various nations who supported his opinion, but were not allowed to express themselves to the press, but were quite open in private conversation.

In March 1933, Jones was determined to get the news of the Ukrainian famine to as big an audience as possible. Instead of running a story, he held a news conference in Berlin, Germany.

Shipton said: “He wasn’t selfish. A lot of reporters would have said ‘this is my story, I want to keep it for myself. ‘ Instead, he wanted to get maximum exposure, highlighting the horrendous treatment meted out by the Stalin regime.”

Shipton believes he made that decision from what he had learnt working in the private office of former Prime Minister David Lloyd George, but also from Ivy Lee, one of the founders of public relations.

“He was well placed to take advantage, together with his own character traits and his own principled background, to get his message across the way that others would not have done.”

Shipton makes it clear that in the book he didn’t want to just glorify Gareth Jones, but also highlight some of his flaws. In terms of his interpretation, Jones didn’t believe that Hitler would come to power. He was writing that a few days before he actually did come to power.

Gareth Jones never forgot his Welsh roots and spoke the language. He was also fluent in English, Russian, French and German. He travelled widely, visiting the U. S. during the Great Depression, and was the first foreign journalist to travel on a plane with Hitler after the Nazis had taken power in Germany. There is also a chapter on Wales and Ireland, subtitled ‘Celtic Culture and Nationalism’.

Jones was killed on the eve of his 30th birthday by bandits in Manchukuo – Japanese-occupied Inner Mongolia – while on a round-the-world fact-finding Tour.

In the book, Jones’ niece, Margaret Siriol Colley, is convinced that her uncle was murdered at the behest of the Japanese for political reasons.

In her book, A Manchukuo Incident, she wrote: “The secrets that he knew died with him. The countries involved have much to answer for and none can be given credit for trying to save him. He was merely a pawn in an international game of chess.”

Colley’s son Nigel, who died in 2018, had another theory. In an MI5 file released in 2002, it identified those with Jones as Mueller, a German and Soviet agent, the driver Anatoli, a White Russian, and Adam Purpis, a banker to the Chinese Communists as well as supplying them with arms. He believed that “together they led Gareth to his murder or in some way were indirectly responsible”.

Shipton’s own view is to accept Nigel’s version, that the death of Gareth Jones was engineered by the Soviets, even though there is no definitive evidence. There are powerful comparisons to be made by what happened in Ukraine in the 1930s, he stresses, and what is happening now.

As before, the Ukrainian nation finds itself in a fight for its very survival.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter