The Ukrainian city of Odesa isn’t just a Russian-speaking city. Odesites consider their way of speaking Russian special – more malleable and refined by dint of exposure to the world at large. It’s a Russian laced with the playful humor of the huge Jewish community that once lived there and tinged by the salt-of-the-earth Ukrainian spoken across the steppes to the north.

Odesa, the “pearl of the Black Sea,” is a cosmopolitan city by design. Founded by the Russian Empress Catherine II in 1792 atop an abandoned Turkish fort, Italian architects were brought in to plan and build a decidedly European city. It quickly became home to Italians, Greeks, Bulgarians, Russians, Ukrainians, and especially Jews. By 1900, an estimated 40 percent of the city’s population was Jewish. Not surprisingly, one of the founding ideologues of Zionism, Ze’ev Jabotinsky (aka Vladimir Yevgenyevich Zhabotinsky) was born there in 1880.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

It’s always been a trader’s city as well, with everyone – from fishmonger to shipping magnate – attentive to profit margins and distribution bottlenecks.

With trade came culture. Since the city was founded at the height of the Enlightenment, its central square was built around an opera theater rather than a church. Writers from all over the Russian Empire would come to Odesa to bask in its balmy “air – filled with all Europe,” as Alexander Pushkin wrote.

‘Risk of Catastrophic Failure’: Watchdog Wants Monitors at Ukrainian NPPs Immediately

Pushkin in the dark. Photo Stash Luczkiw

And not just Pushkin, Odesa’s streets are named after a pantheon of Russian-language writers: Bunin, Chekhov, Tolstoy, even the Ukrainian Russophone Mykola Hohol (better known as Nikolai Gogol) have streets named after them. The Yiddish-language writer Sholem Aleichem, from the Poltava region, lived in Odesa for years, writing in Russian for Voskhod, the Jewish periodical.

But the best-known Odesite writer was its native son, Isaac Babel, whose stories of the Russian Civil War, collected in Red Cavalry, became required reading in the Soviet Union. His Odessa Tales were set amid the city’s criminal underworld, which eventually emigrated to Brooklyn’s Brighton Beach neighborhood (called Little Odesa), where a satellite base for the Russian-Jewish mafia was established during the 1970s.

Ukrainian stakes its place

Odesa is no stranger to conflict, but the Russian attacks on the city since February 2022 have galvanized its citizens. As in much of Ukraine, it’s often the Russian-speakers who are most appalled by Moscow’s attempts to rein them back into its autocratic fold.

Since January 2021, the Ukrainian government has implemented the law “On Ensuring the Functioning of Ukrainian as the State Language.” As a result, “all service providers, irrespective of the form of ownership, are obliged to serve consumers and provide information on goods and services in the state language [Ukrainian]. Only upon request of the customer can the service be conducted in another language.”

To many Odesites that just seems weird, if not draconic. But as in most mercantile cities, shop owners and sellers will speak whatever their customers prefer to speak. Russian is still the language heard on the street, but by now everyone understands Ukrainian, and many locals will pepper their conversations patriotically with Ukrainian, developing a local variety of Surzhyk – that mix of Ukrainian and Russian heard across most of the country.

Yet Odesites are also very pragmatic and realistic; they understand that the Ukrainian language may never rise up from under the weight of Russian – for centuries the Eurasian lingua franca – without legislative help.

A new Surzhyk

One Russian writer, Julia Belomlynska, settled in Odesa and refuses return to her native St. Petersburg. For a while she performed with a troupe singing folk songs of the Lemko region in the Ukrainian Carpathians.

“In my opinion, real poets create their own linguistic worlds, and this is always a kind of Surzhyk, a rainbow of neologisms,” she says.

“In Odessa everyone speaks however they feel, and probably a new Surzhyk is being born before my eyes. Not the Surzhyk imported from the villages, but the Surzhyk of artistic Odesa – from artists and street musicians, various performers, not philologists who speak beautiful literary Ukrainian.”

Maryna Zaburanna under a photo of Mykola Hohol at Odesa’s Gogol Mogol restaurant. Photo Stash Luczkiw

Literary Ukrainian in Odesa

Yet there is one person who has made it her mission to help literary Ukrainian flourish in Odesa: Maryna Zaburanna. Originally from Sharapanivka, a village near the Moldovan border north of Odesa, the 28-year-old Ukrainian language teacher at the Odesa College of Computer Technology is also the author of From the Pocket Between the Ribs, a collection of love poems in the broadest sense.

Her poetry celebrates traditional Ukrainian motifs – “the cherry orchard by the house,” she calls it, referring to one of Taras Shevchenko’s more bucolic poems. But she has greater ambitions than just composing poetry. She is editing a Ukrainian literary journal called Hamarton, which means tuning fork, and the first issue is now being proofread and prepared for print.

“When I told my friends and colleagues that I was founding a Ukrainian literary journal, in Odesa, they all said, ‘I’ll believe it when I see it.’” For most literati familiar with Odesa, the Russian tradition has tenacious roots, and the city’s imperial-cosmopolitan lymph still courses through the intelligentsia.

But even Odesa’s intelligentsia nurtures a prevailing sense of uprootedness, which is now facilitating a tendency to embrace Ukrainian. And not just among intellectuals, the youth are also speaking Ukrainian more.

Since Russia’s full-on attack, Odesa has seen an influx of internally displaced persons from the eastern part of the country now under occupation. Zaburanna’s mother’s family is from Mariupol; when Ukraine’s other port city first came under Russian occupation, maintaining contact became an ordeal and trying to either get help in or bring others out was extremely difficult.

Many of the refugees from the occupied regions – such as the Donbas or the Kherson region – began coming to the Ukrainian conversation clubs Zaburanna helped organize. Even local Odesites take part. The clubs also serve as support groups, especially for the elderly. Many of the participants admit: “I can’t stand speaking the language of the enemy anymore.”

For Zaburanna, such a change of heart is already a victory, which has made it easy for her to embrace the city as her new home. “Odesa has a Ukrainian heart,” she says. “It accepts everything with warmth and love, like an elegant grandmother hugging you.”

And despite much of her family being separated by circumstances, Zaburanna insists on exalting love: “I’ll write about love to keep the pain of war at bay…”

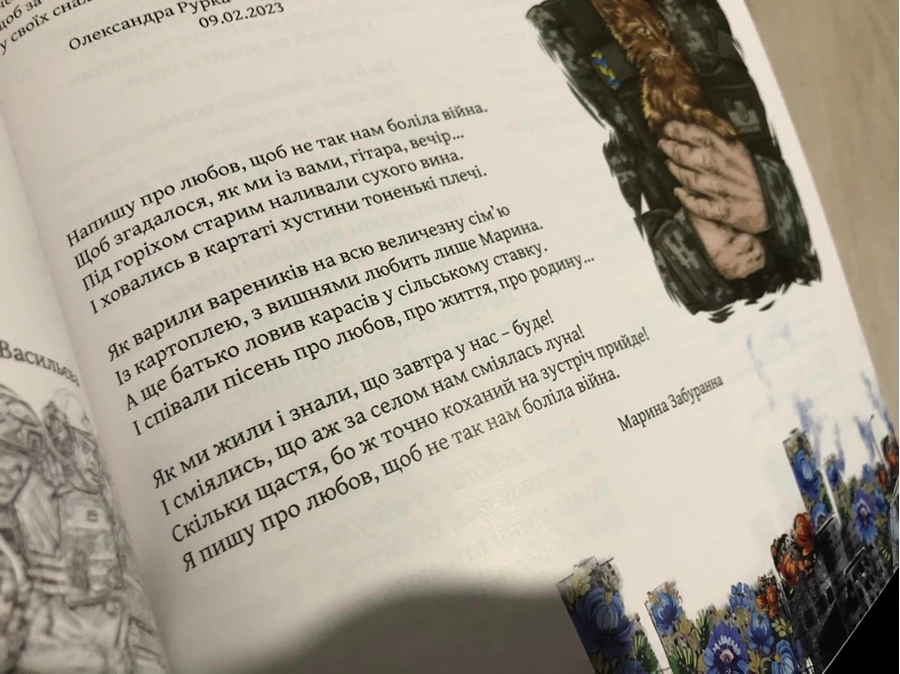

Poem: “I’ll write about love to keep the pain of war at bay,” by Maryna Zaburanna

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter