After lunch, on a sunny summer day, cars entered a parking lot near a busy Kyiv supermarket. At first glance, there seemed to be nothing remarkable in the procession of pedestrians and vehicles.

Out of the stream of automobiles coming and going, a small white Mercedes Sprinter bus appeared with no logos or advertising to distinguish it.

But one thing separated this bus from the others – its passengers were on their way to Moscow.

While it’s not illegal for Ukrainians to travel between Kyiv and Moscow, it isn’t the sort of thing a bus company is going to widely advertise these days and hasn’t been since 2014 – when Russia annexed Crimea and started a bloody war in the Donbas.

However, even now, in 2023, over a year-and-a-half into Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, there are still Ukrainians traveling to Moscow, many doing it in ways that leave no Russian stamps on their passports.

“Nobody will be able to tell you the number of Ukrainians who are employed in Moscow and the Russian Federation as a whole,” Head of the Department of Communications and Electronic Services of the State Migration Service of Ukraine, Serhiy Gunko, told Kyiv Post.

Why they’re traveling to Moscow

According to a 2011 poll, nearly half of Ukrainians had relatives in Russia.

Meanwhile, according to a 2015 study, 2.6 million Ukrainian citizens were living in Russia.

Some Ukrainian citizens, including one woman who was on the bus, travel to Russia for work.

EXPLAINED: What We Know About Russia’s Oreshnik Missile Fired on Ukraine

However, most who spoke with Kyiv Post were traveling to Moscow to see their family members in Russia and the Russian-occupied territories.

To blend in while in Moscow, some Ukrainians tend to keep their origins secret, at least initially.

“It is logical that I just don't say that I am from Ukraine," a man who said he travels to Russia for family reasons told Kyiv Post.

On one Telegram channel, where Ukrainians reach out to each other for advice on traveling back and forth between the two countries, a woman wondered whether her husband’s being in the Ukrainian military would cause her problems.

Meanwhile, some on the forums say that parts of the Russian population are sympathetic to Ukrainians.

“The people I talk to (in Russia) are against the war, but they don't advertise it,” the man said.

Echoing this, a Ukrainian woman, who said she lives in Moscow, claimed that many of her Russian friends supported Ukraine and even donated to its armed forces.

“This does not remove responsibility from them. After all, society in the context of the nation is responsible for the actions of the authorities of its country,” she added.

The bus to Russia

A seat on the bus costs $350 in cash, handed over on the day to a typically grim-faced bus driver.

Passengers can depart from 16 cities in Ukraine, including occupied Luhansk.

From Kyiv, the bus picks up passengers bound for Moscow every three days. A bus also leaves from Moscow with passengers bound for Kyiv every three days.

With fierce fighting raging along Ukraine’s border with Russia to the east, the route to Moscow is circuitous.

Today’s bus was to head west to Poland where passengers were to transfer to at least one more bus, equally unremarkable, and continue their journey through Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia – all the way to Moscow.

The bus was far from full, just a handful of travelers, all women largely due to men aged between 18-60 not being allowed to leave Ukraine under martial law.

One of the women said she was traveling to Moscow for work and had made this trip several times before. Getting to Moscow can take anywhere from a few days to over a week, she said. One of the main variables is the border guard.

A few weeks ago, the woman’s friend had to wait at the Russian border control for five days.

The elderly woman in the back of the bus said that this was her first time going to Russia since it started its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

She planned to visit her relatives and felt very nervous about crossing the border.

What do you think of Russia’s ‘special military operation?

Crossing the border

According to online forums, upon reaching the Russian border control, people fill out questionnaires and are usually lined up in a big queue outside the building where they’re to be interviewed.

Once inside the building, they first go to a waiting room, with space for ten people at a time. After, they enter a second room where they’re individually questioned.

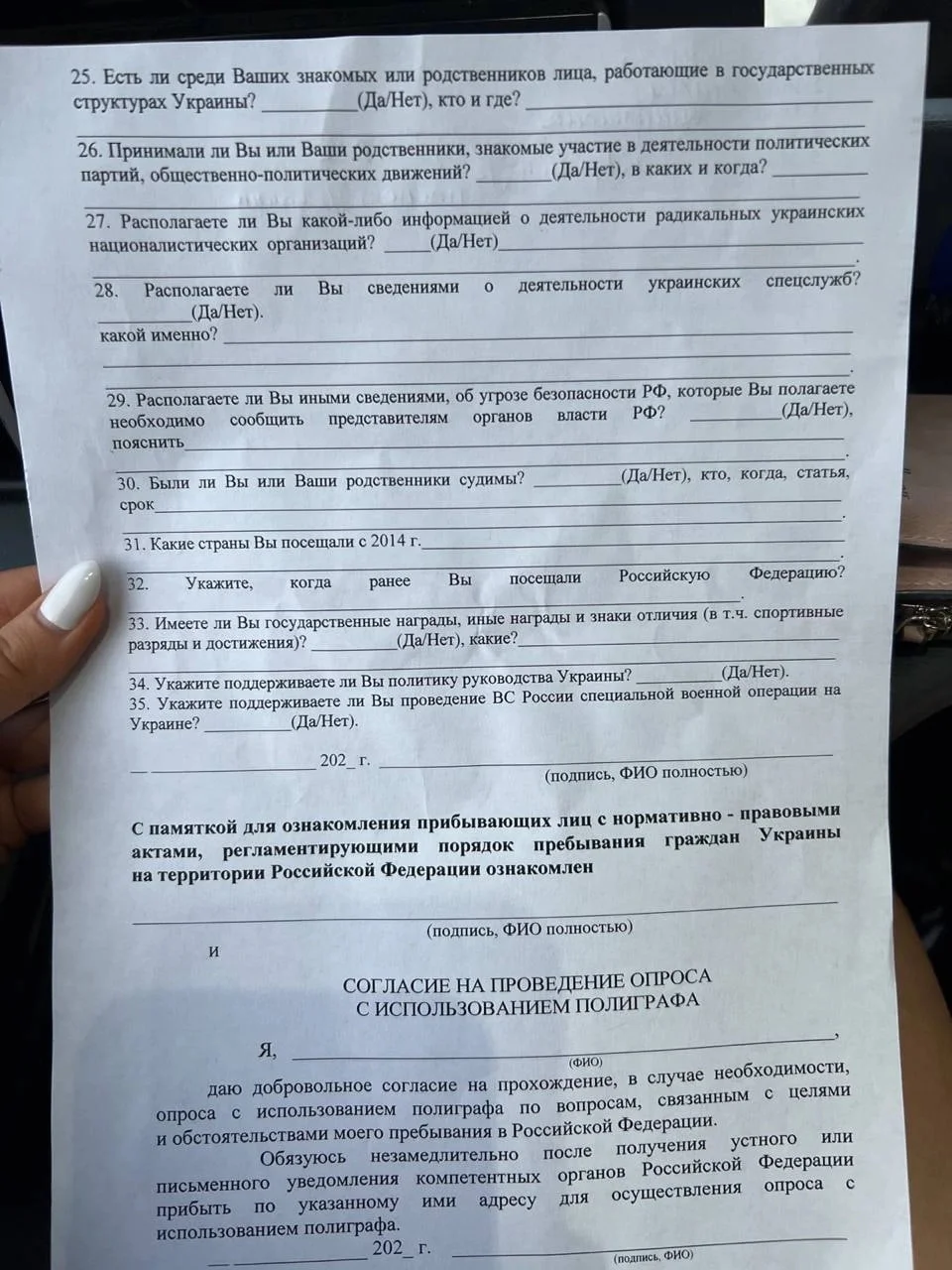

A form must be filled in giving consent to be taken for a lie detector test at any time during your stay in Moscow.

The guards are known to ask questions about your life, family, work, and political views – things like “What do you think of Russia’s ‘special military operation?’” and “Have you ever worked for the Ukrainian security services?”

They can sometimes apply pressure or may question you for hours, people on Telegram and VK, a popular Russian social media platform, say.

Along with the interrogation, the Russian border service also checks passengers’ phones, particularly archived messages and marked locations on social networks.

According to those who have made the crossing, the border service sometimes even restores deleted messages.

One Ukrainian said that they keep a second phone – complete with different social media accounts – so that they won’t be bothered by the border guard about having Ukrainian content or locations on their phone.

To avoid hassles, people traveling back and forth between Russia and Ukraine are often keen to hide the fact that they’re doing so from both Russian and Ukrainian authorities.

I just don't say that I am from Ukraine

Avoiding the passport stamp

One way that passengers hide their visits between Russia and Ukraine is by not getting their Ukrainian passports stamped when they cross into Russia.

It’s possible to do this because Russia allows Ukrainians to enter Russia with only a Ukrainian-government-issued ID.

Once in Russia, Ukrainians get a migration card that allows them to stay there for 90 days.

The fine for staying longer than 90 days is 5,000 rubles (about $53).

Naturally, re-entering Estonia with a stamp showing that you’ve left the Schengen Zone, but no stamp showing that you’ve entered Russia is against the law and raises suspicions, Peter Maran, the head of Estonia’s southeastern border checkpoint told Kyiv Post.

He said that a similar practice is also often used by people who have dual Estonian and Russian citizenship.

“In these cases, the employee of the Estonian border control point usually asks for additional documents and conducts a thorough inspection, including baggage checks,” Maran said.

“There were situations when, during an in-depth check, employees found hidden Russian passports on citizens or that Ukrainian citizens had hidden their foreign passports, claiming that they only had internal ones,” he added.

When this happens, Estonian border guards find out why the person tried to hide their documents. They then assess whether they’re a threat.

There have been times when the Estonian Border Guard has received fake information about people’s identities or their reasons for traveling — and they’ve been refused entry, he said.

In a phone conversation with Kyiv Post, Andriy Demchenko, assistant to the head of the state border service of Ukraine, said it can be difficult to determine where someone has been when it’s not shown in their passports.

"But of course, the state border service and other law enforcement agencies, if necessary, in relation to individuals who arouse suspicion, can work closely with the border guards of European countries in order to establish the information that interests us," Demchenko said.

Coming to Ukraine from Russia

As a part of its campaign to take control of Ukraine, Moscow attempts to turn Ukrainians into Russians and has made it easy for them to get Russian documents, and even difficult to work, study, or receive government assistance in occupied territories without them.

While you’ll be let in, if you accept Russian documents and then try to travel to Ukraine with them, they’ll be confiscated and you might receive abusive comments, a woman from one of the online forums told Kyiv Post.

Meanwhile, it’s generally difficult for Russians to come to Ukraine, as Kyiv attempts to keep out spies and saboteurs.

A little more than 50 Russians have gotten new visas to Ukraine, and of these, only 44 were permitted to cross the border into Ukraine since July 1, 2022, when Kyiv passed legislation requiring that they get special invitations and pass through law enforcement agencies’ checks, Demchenko said.

That said, the number of Russian citizens living in Ukraine is much larger – as those who had already been living in the country can still apply to renew their residency permits when they expire.

From March 2022 to June 2023, 1,518 temporary residence permits and 2,106 permanent residence permits were issued to Russian citizens, Head of the State Migration Service Nataly Naumenko, told Kyiv Post.

A Russian can be eligible to live in Ukraine if they have Ukrainian family, serve in the Ukrainian army, or are of special interest to the state, Naumenko said.

Meanwhile, the circuitous bus route described above is not the only way to travel between Russia and Ukraine.

On Telegram and VK for instance, people also talk about the Mokrany-Domanovo pedestrian corridor between Belarus and Ukraine and the Kolotilovka checkpoint, in Russia’s Belgorod region.

From these locations, it’s possible to enter Ukraine with Ukrainian documents, although generally not possible to go to Belarus or to Russia.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter