David Burliuk was born on July 21, 1882, in a small village near Kharkiv. There were six children in the family with deep Ukrainian Cossack roots on his father's side, and Belarusian on his mother's. Two of them, Volodymyr and Lyudmila, also became artists, and David’s brother Mykola became a poet. The part of his memoirs where David describes his childhood can be reduced to one phrase: he drew all the time. His schoolmates called him an artist, and the local art teacher wrote to his mother that the boy had “God-blessed talent.”

David first visited a big museum when he was 15, and it was the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. As he wrote later, for the next seven years he was influenced by Repin, Shishkin, Serov, Kuindzhi and other Russian realists, but then his idols became his opponents. Repin said about an exhibition of Burliuk’s paintings: “These followers of Cezanne are ruining paintings with their donkey tails!”

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

During the first decade of the 20th century, Burliuk studied arts in Odesa and Kazan, at the Munich Royal Academy of Arts, and at École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His exuberant, extroverted character was recognized by Anton Ažbe, his professor at the Munich Academy who called him “a wonderful wild steppe horse.”

While on a three-month summer vacation in Odesa, he drew more than 350 sketches. He spent 20 hours a day drawing or painting and never seemed to be tired. A shocked teacher told him, “This isn’t art. This is factory rubberstamping!” But Burliuk ignored his teacher’s admonishment and carried on.

Portrait of a Book Fair in War Time

His art was an amalgam of Fauvist, Cubist, and Futurist influences, which he absorbed and melded with his love of nature and fascination for the forms and designs of Scythian culture. He gathered a group of writers, poets and artists called “Hylaea” – the Greek name of the Scythian lands around the mouth of the Dnipro River, which Herodotus mentioned describing Hercules's feats. The name may have been inspired by drawings on old maps that showed Hercules resting by the Dnipro after his victories.

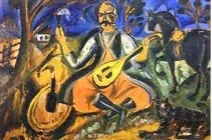

Burliuk had a special admiration for Ukrainian folklore. One of his favorites was the legend of Mamai, a Cossack who embodied the artist’s own vision of bravery, self-sufficiency, and rugged individualism.

Cossack Mamai, 1912

Burliuk’s appearance was uncommon, to say the least: he was short but with a massive and somewhat clumsy body. His contemporaries wrote that his bombastic face resembled that of a fat lizard. He even took pride in his left glass eye that he had from his early years. He liked all women without exception, and the more voluptuous the better. And he considered his own thirst for creativity a sexual sign, an instinctive urge for self-reproduction.

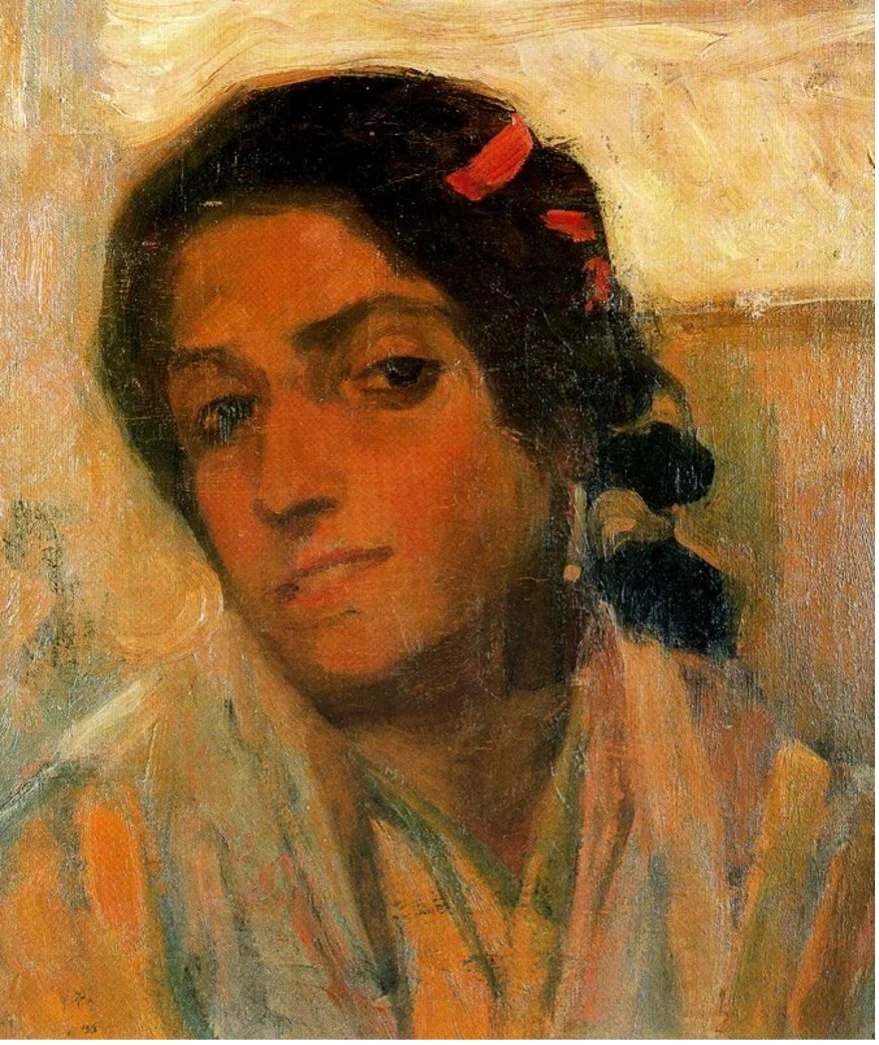

In 1912, he married Marussia Viazemskaya, the woman he always called the love of his life. The young couple lived in a hotel suite in downtown Moscow where singing and playing music was allowed from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m. Friends called it a “Music Nest.” It was where he and his fellow Futurists produced perhaps the most provocative of the Futurist manifestoes titled “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste.”

Portrait of Marussia Viazemskaya, 1912

Burliuk took an active part in avant-garde exhibitions in Kyiv, Moscow, St. Petersburg and Munich. In early 1914, when the notoriety of Futurists reached its peak, David Burliuk, Vladimir Mayakovsky and Vasily Kamensky toured 17 cities across the Russian Empire, wearing gaudy waistcoats and carrots in their lapels and sometimes animals painted on their faces. Their extravagant appearances and performances, which included drinking tea and reciting poetry on stage under a suspended piano, drew packed audiences. They scandalized many, but also won converts to the new art.

Burliuk was friends with the great avant-garde artists Mikhail Larionov and Vasily Kandinsky and was a member of several groups, most prominently Jack of Diamonds that included Kazimir Malevich. Mayakovski later wrote: “He was a great friend, my true teacher. Burliuk made me a poet. He read me the French and Germans and shoved books at me. He walked and talked and never let go for a second. He gave me 50 kopeks a day so I wouldn't be too hungry to write.” Mayakovski also mentioned Burliuk in one of his best-known poems, A Cloud Wearing Trousers.

From 1915 to 1917, Burliuk resided in the Urals and frequently went to Moscow and Petrograd. After the 1917 Bolshevik coup he spent several years traveling to Siberia, Japan and Canada. In Siberia he gave Futurist concerts and sold his works. In Japan and Canada, he painted, organized exhibitions and promoted Futurism.

In 1922, Burliuk and his wife moved to the United States and settled first in New York City where he lived until 1941, and then in Hampton Bays, Long Island, where he lived his last two decades.

While in exile he closely followed developments in his native Ukraine, where during the mid-1920s there was a brief period during which controls over cultural life were relaxed and “Ukrainianization” officially promoted. In 1925 he was a co-founder of the Association of Revolutionary Masters of Ukraine.

In 1940, Burliuk petitioned the Soviet government to allow him to visit his homeland. In exchange, he offered a sizeable collection of archival material pertaining to his contemporary and friend, the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. His request was turned down. He was only allowed to visit the USSR twice – in 1956 and 1965.

His repeated requests to publish a collection of his works in the USSR were also ignored. He sent his paintings to the USSR Union of Artists but never got any response. Burliuk was perplexed and desperate: he could not understand why his name had been blotted out in the annals of the art that he himself had built.

Despite his age, Burliuk traveled very frequently and was always accompanied by his wife. In 1962, they traveled to Brisbane to hold an exhibition at Moreton Galleries. There, Burliuk made some sketches of Australian landscapes.

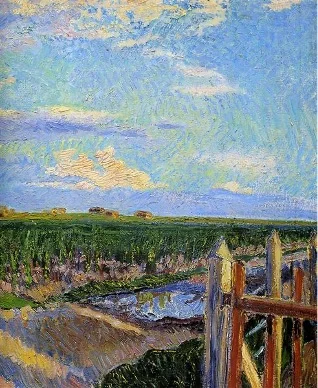

From 1937 to 1966, the Burliuks published Color & Rhyme, a journal featuring primarily the artist’s activities. Worshipping the earth’s abundance and glory, Burliuk had the reputation of a Futurist scandalizer of public taste. Quite naturally, one of his favorite artists was Vincent van Gogh with his impassioned vision of nature tendered with brilliant colors and vigorous strokes.

Artistically, Burliuk adhered to the belief that painting should capture life’s experiences and interact with visual concerns of the day. His work in numerous artistic styles suggests his desire to embrace contemporary developments and new ways of thinking.

He explained his artistic views in lectures and at exhibition openings.

His 1908 landscape Morning, Wind painted in wide brushstrokes and viscous impasto is associated with many of Van Gogh’s paintings, while Cossack Mamai demonstrates a concern with fauvist color relationships and ethnographic Scythian motifs.

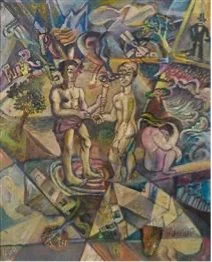

Similarly, he explored the relationship of planes and geometric forms through Cubo-futurist esthetics.

Cubo-futurist composition

He wrote: “Let your eyes rest upon the surfaces of my pictures.... I throw pigments with brushes, with a palette knife, smear them on my fingers, and splash the colors from the tubes.... Visual topography is the appreciation of paintings from the characteristics of their surfaces. The surfaces of my paintings are laminated, soft, glossy, glassy, tender as a woman's breast, slick as a maiden’s lips or rose petals, flat and dusty, flat and dull, smoothly even and mossy, dead, sand, hairy, deep shelled, shallow shelled, shell-like, roughly hewn, faintly cratered, grained, splintery, rocky, craterous, thorny, prickly, camel-backed etc. In my works you will find every kind of surface one is able to imagine or meet in the labyrinths of life.”

Burliuk loved vitality in all its forms – biological, psychological and cultural. Painting his native Ukrainian steppe, or Japanese landscapes, or Long Island fishing villages, or New York streets, he searched for vibrating energy and hidden patterns.

He died in Hampton Bays in 1967 at the age of 85. That same year he was posthumously inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His house and studio are still there.

David Burliuk and his wife Marussia, 1966

Very regrettably, Burliuk’s impressively voluminous artistic legacy obscured by decades of Communist rule remains unexplored and unappreciated to this day. Hundreds of his poems, stories, novels and essays remain unpublished and almost a thousand paintings are scattered across Russia.

A lot of his paintings have been sold at auctions at prices ranging from $125 to over $500,000. Only a small part of his artwork can be found in his homeland.

With such an incredible multitude of drawings and paintings, his heart was dedicated to painting two portraits: of his loving wife and of Ukraine.

Ukrainian landscape, 1921

From the day he left Ukraine and for the whole rest of his life he dreamed to come back to his homeland someday. He never made it, but his ashes must have reached the shores of Ukraine after his relatives dispersed them over the Atlantic Ocean, as he willed.

Although Russia in its typical imperialistic way has claimed Burliuk along with many other non-Russian cultural figures as "theirs," he in his autobiographical essay Memoirs of a Futurist declared: “Ukraine has its most faithful son in me. The bones of my ancestors are in Ukraine.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter