As the clock ticks down on the May 18 expiry date of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, Ukraine’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations blasted Russia in the Security Council yesterday, May 16, for “blackmailing the world” amid further evidence of illegal Russian grain smuggling and warnings of world hunger and refugee crises.

Sergiy Kyslytsya also accused Russia of “pretending to suffer from [the grain agreement], while, in fact, [its] grain exports have doubled.”

“It is disgusting that Russia still pretends to be on the losing side of the deal. I will not even remind the Council of the immorality of such complaints from the aggressor state, which has been and remains the only threat to food shipments in the Black Sea,” Kyslytsya said, noting that Russian wheat exports in January-February 2023 almost doubled year on year.

“We therefore consider these speculations to be an attempt to whitewash Russian deliberate practices to weaponize food supplies and we urge the international community to give a resolute response,” he added.

Russian blackmail

As previously reported by Kyiv Post, with apparent backing by the UN, Russia seems to be insisting on the resumption of the Togliatti-Odesa ammonia pipeline, the world’s longest, which runs through Ukraine, as a requirement of renewing the grain deal.

The pipeline ships products from TogliattiAzot, one of Russia’s largest ammonia and fertilizer producers which claims to serve 11 percent of the global market for ammonia, with its primary markets being in Turkey, India and Brazil.

ISW Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, November, 24, 2024

The company was recently taken over by Dmitry Mazepin, who is described as a close ally of Vladimir Putin and reportedly one of Russia’s wealthiest 100 people with a personal fortune over $900 million. He is currently subject to EU and UK sanctions and is being pursued by Italian authorities in relation to the disappearance of two yachts prior to their confiscation under sanctions.

Ghost ships and grain piracy

As the UN debate about the grain deal escalated, further evidence has emerged of Russia using “ghost ships” of grain outside the agreement.

Satellite images released last week by the investigative organization Bellingcat appear to show Russian “ghost ships” suspected of transporting stolen Ukrainian grain at an internationally sanctioned shipping terminal in the Black Sea.

The 140 images appear to show ships at the Avlita terminal in the port of Sevastopol in Ukraine’s Russian-occupied Crimean peninsula.

Under shipping law, vessels must have their Automated Identification Systems (AIS) satellite transponders turned on while at sea to show their location. Data from transponders suggests that very few have visited Avlita in recent years.

However, the images analyzed by Bellingcat tell a different story.

A ship at the Avlita terminal in Sevastopol on July 24, 2022.

“Bellingcat identified at least 179 days in the first 12 months of Russia’s full-scale invasion where ships had been present at the Avlita terminal with their AIS transponders seemingly turned off,” said Ollie Balinger, Bellingcat’s geocomputational specialist.

A ship detection tool using satellite radars was also used to identify vessels at the terminal.

The results of Bellingcat’s investigation support previous reports showing that Russia is using the Avlita terminal to transport stolen Ukrainian grain.

In October, AP used satellite imagery and marine radio transponder data to track three dozen ships making more than 50 voyages carrying grain from Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine to ports in Turkey, Syria, Lebanon and other countries as part of a massive smuggling operation.

According to a BBC investigation last year, the grain is stolen by the Russian military from farmland in the parts of Ukraine it has occupied, loaded into trucks, and transported to Russia or Crimea.

In Crimea, it is mixed with Russian grain and given a fake export certificate, the report said. It is then transported on “ghost ships” that appear in some cases to transfer their cargoes to other ships while at sea.

The ultimate destination of the ships is unclear, and many ports refuse to dock Crimean ships carrying grain, but some of them were detected at Syrian ports, Bellingcat reported.

The Ukrainian government in April accused Russia of stealing “several hundred thousand tons” of grain in the wake of last year’s invasion, and Russia denied the accusation, Reuters reported.

Russian smuggling of grain is in addition to other means to sabotage the agreement, Kyslytsya alleged yesterday.

As revealed by a Kyiv Post analysis, grain shipments under the deal are down by 46 percent in May, and the inspection rate of ships has dropped to an average of 2.9 inspections per day, compared to 6.6 in the period of August 2022 to April 2023.

“In April, we were able to export through the grain corridor less than 3 million tons, which is only half of our agricultural export capacities,” Kyslytsya said.

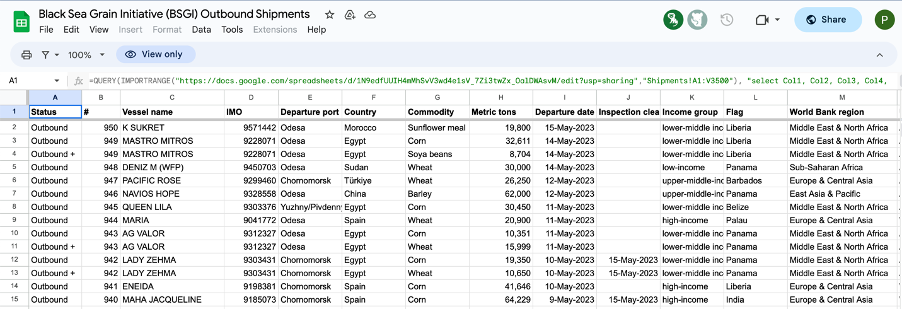

Further analysis of UN data by Kyiv Post shows that in the week from May 9 to May 16, only 14 ships carrying 392,940 tons of Ukrainian wheat, corn, barley, soya beans and sunflower meal left Black Sea ports. Only one of those ships – carrying 30,000 tons of wheat – was bound for a low-income destination, e.g., sub-Saharan Africa.

International ramifications

The Ukrainian government also expressed strong concerns on May 15 about the impact of the cessation of Black Sea grain exports on world hunger and global migration.

Olga Trofimtseva, Ambassador-at-Large of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, told a Kyiv briefing that if the supply of Ukrainian grain to countries on the verge of starvation is stopped, the citizens of these countries will face food shortages within two to three weeks, and that refugee flows to the EU will increase in a month at the most.

“The negative consequences of stopping the grain corridor will be felt almost immediately by those countries that receive humanitarian food from Ukraine, as they are unable to accumulate sufficient stocks,” Trofimtseva said.

“If the grain corridor stops now, including deliveries under the humanitarian program Grain from Ukraine, it will be more difficult to physically export grain because we’ll have to do it through the EU, which will take longer,” she continued.

“We understand that we will not be able to transport such volumes by road and rail at once. This will have a corresponding impact on the food and social security situation on the African continent, especially in those countries that depend on the UN World Food Program.”

Trofimsteva indicated that negotiations about renewing the grain deal are not currently taking place.

Under the grain deal, Ukraine has exported more than 3 million tons of food to African countries through seaports, including almost 1 million tons shipped to countries in need. Approximately 50 percent of that was within the framework of the UN food humanitarian programs and Grain from Ukraine.

The Grain from Ukraine program was initiated by President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky. It involves the purchase of Ukrainian grain by partner countries and its transfer to countries affected by the humanitarian crisis. The program is implemented in partnership with the World Food Program under the auspices of the UN.

The Joint Coordination Centre (JCC) established by the UN to implement the Black Sea Grain Initiative has issued no public information about the status of negotiations since May 11. Kyiv Post has submitted a series of questions to it.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter