Receiving the death sentence was “worrying” says 29-year-old Aiden Aslin from Nottingham, England. Aslin served in Ukraine’s 36th Marine Brigade before being taken as a prisoner of war (POW) in the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR). He believed that the Russian-backed court would “have to carry out” the death sentence or be at risk of “looking weak.”

In 2018, Aslin, who had previously fought against Islamic State in Syria, emigrated to Ukraine. He joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), moved to the city of Mykolaiv and was soon engaged to be married.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Life was going well for Aslin. He had completed three deployments on the frontline in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region when Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022.

“We were pushed back to Mariupol, and after a month and a half, we were forced to surrender,” he recalls.

In a calm voice, the former Ukrainian Marine describes his time in captivity in the self-declared DPR as “absolute hell.”

“We were in cells for two, but I had five guys in my cell… I was stabbed, beaten, psychologically tortured and forced to take part in propaganda,” he tells Kyiv Post.

In one horrific recollection, he mentions seeing the occupying forces murder a prisoner in the adjacent cell.

Russia Hurls Intercontinental Missile at Ukraine: A Shocking Escalation

“When a new POW came in, they did this thing called ‘the gauntlet,' where they put a bag on your head and made you crawl to the cell from the processing area. While you crawled, they would beat you.”

Aslin describes one situation where a new prisoner was crawling to his cell and seemed to pass out or fall unconscious.” The military guard “kept yelling” at the motionless Ukrainian POW, became enraged and proceeded “to beat him to death with his police baton.” Eventually, a medic arrived and declared the Ukrainian POW to be deceased, Aslin recounts.

During his time in captivity, Aslin mentions having the unpleasant experience of meeting Graham Phillips, a fellow Briton who moved to Russia some years ago and was sanctioned by the British government after producing pro-Kremlin content.

Describing Phillips as seemingly “normal when off camera,” he says the Russian propagandist became “psychotic” when the cameras turned on and it was time to start asking questions of POWs.

Eventually, Aslin was exchanged through a Saudi Arabian-organized prisoner swap. He was transported from Donetsk to Rostov, and from there flown to Saudi Arabia and back to the UK.

Whilst life in England is certainly calmer, Aslin is not content. But upon trying to return to Ukraine – which he now views very much as home – he encountered a problem.

Unexplained Schengen ban

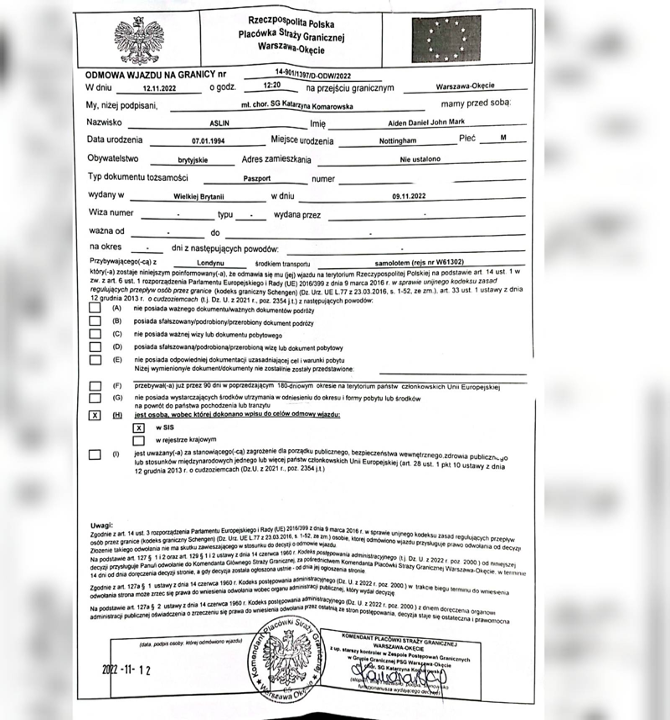

Aslin explains: “When I got to Poland, [the authorities] said there was a ban on me entering the Schengen Zone.” He added that “the Polish officials did not know what the reason was, so I was deported back to Britain.”

The deportation order leaves the reason for deportation blank, other than mentioning that it was requested by a Schengen country, in this case Germany.

The Polish deportation letter does not indicate the reason for Aslin’s deportation, other than that an alert has been issued for the purpose of refusing entry.

Attempting to get back to Ukraine without entering the Schengen Zone, Aslin flew the following week to Chisinau, Moldova. However, the Moldovan authorities wanted to know why he was deported from Poland, so again deported Aslin back to the UK.

Surreal experience

The whole experience has been surreal for Aslin. “The Germans put me on this blacklist while I was in captivity; and now I'm out of captivity but I’m still not free.”

He adds: “I just hope that the German authorities look into this and correct what was almost certainly a good-faith error, but this has put my life on hold,” he adds.

Aslin’s lawyers believe the reason for the temporary ban, set to expire in October of this year, to be unrelated to Aslin’s earlier involvement in Syria. Instead, they think it is more likely due to German concerns, at the time of his abduction by occupying authorities in the so-called DPR, that his passport could be used on the black market or by Russia to covertly bring a Russian national into the European Union.

“I am engaged to my fiancée and I have a home in Mykolaiv, I simply want to get on with my life and to spend the rest of it in the country for which I fought. But right now, I am stuck here without the ability to get home.”

Unseen award

In late 2022, President Volodymyr Zelensky gave Aslin an award for “personal courage and selfless actions shown in the defense of the state sovereignty of Ukraine” – an award that Aslin has still not seen with his own eyes.

“I was invited to Kyiv on Dec. 4 for the ceremony, but I was unable to attend due to the travel ban [in the Schengen Zone]” he explains.

Despite his veteran status, Aslin is not yet a citizen of Ukraine, which he would like. “I’m in the process of becoming a Ukrainian citizen, however it’s currently frozen since I cannot travel to Ukraine,” he says.

Aslin also has been given “victim of war crime status” by the Ukrainian authorities, but he is unable to give testimony or help Ukrainian investigators research Russian war crimes, as he needs to “be in Ukraine to speak to them about the crimes as a witness.”

The pains of war are still fresh on Aslin’s memory, which he describes as “psychologically difficult.” He has also been unable to reunite with friends with whom he was in captivity.

“I wanted to meet my Battalion Commander who I spent my first month in captivity with when we got released [as well as] my Major, Viktor.”

“The Major got released a month after me and I was hoping to go and see him, but wasn't able to because of the travel ban… so it's been a lot harder because I have no one with whom I can speak who has gone through the same experience as me.”

Despite a record of heroism, there currently remains an untraversable continent and a mysterious temporary ban separating the Ukrainian veteran from Ukraine.

Aiden Aslin with his fiancée, a native of Ukraine, now residing with him in Britain.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter