'Six Ways Ukraine is Winning' is a collaboration between Kyiv Post and Byline Times, highlighting Ukrainian ingenuity, resilience and determination in the face of one year of Russia's full-scale invasion.

After a year of full-on conventional war and millions of shells hurled downrange, Ukraine’s artillery officers and men have built up a pretty solid reputation for flexibility and innovation, maybe even on par with NATO – but the time they put howitzers on barges to win a naval victory was really outside the box.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

On June 17 two Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) cannon opened fire on Zmiinyi Island, a strategic outcrop in the northwest Black Sea about 40 kilometers off Ukraine’s coast.

Occupied by Moscow’s troops at the start of the war, the island had been converted by the Kremlin into a maritime fortification bristling with weapons and controlling shipping routes between Istanbul, Romania, Bulgaria and Ukraine.

Hitting the Russians wasn’t going to be easy. The coastline was swamp and wetland, and the closest road capable of handling a 28-ton howitzer was a good 80 kilometers away from even sketchy potential firing positions.

The maximum range of cannon available for the job (38 kilometers, though just maybe that might be pushed) probably wasn’t enough to reach the island; and even if it was, the moment the Ukrainians opened fire they would face a real risk of one or both of their field pieces sinking into the bog.

As it worked out, sweating Ukrainian gunners had to battle mud and soft ground, mosquitoes and sunburn, but 13 days later the bombardment of Zmiinyi was complete, the Russians had sailed away, and military history had notched up another uniquely Ukrainian artillery success.

Day after day gun crews, drone operators, communications sergeants, barge captains and engineers teamed up to drag howitzers twice the weight of John Deere harvesters off barges onto a bit of dry shore, thump out 80 to 100 NATO-standard 155mm shells over the horizon at Zmiinyi Island, and then load up and sail away to a hide position and hopefully some food and sleep, before doing it all over again the next day.

In its later stages, reinforced with less-accurate, long-range rockets, the AFU artillery attack saturated the 1.5 square kilometer rocky island with high explosives. The Russians fired back, but missed.

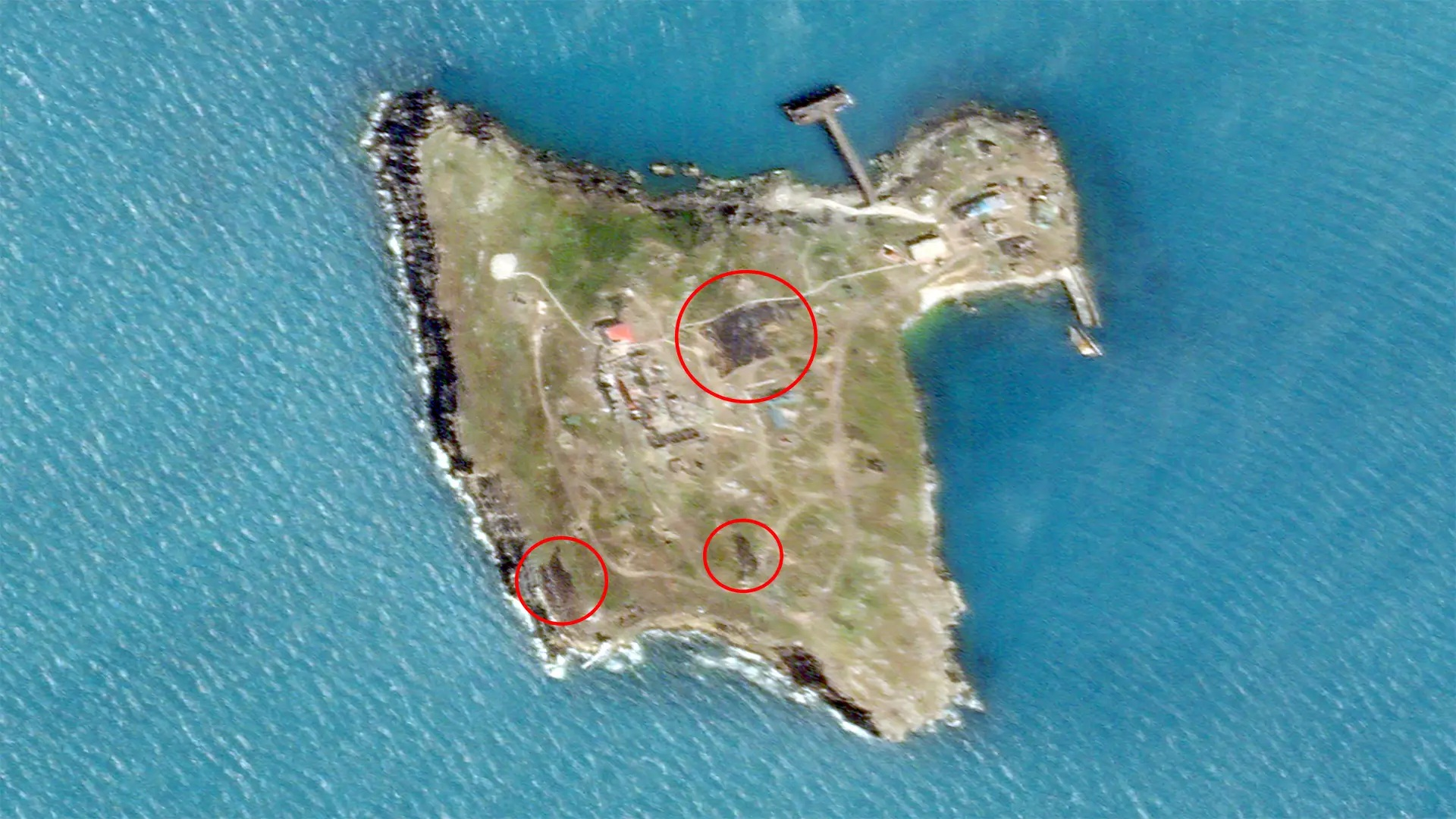

AFU special forces infantry aboard small boats landed a week later to find a moonscape; practically every combat vehicle, crew-served weapon, surveillance radar and supply depot placed by the Kremlin on Zmiinyi Island – where they assumed it all to be safely outside the range of the Ukrainian guns – had been trashed.

Satellite image of hits and damage casued by a Ukrainian artillery bombardment of Russia-occupied Zmeyniy Island, taken on June 21, 2022. PHOTO: Mil.In.Ua.

Satellite image of hits and damage casued by a Ukrainian artillery bombardment of Russia-occupied Zmeyniy Island, taken on June 21, 2022. PHOTO: Mil.In.Ua.

Ukrainian army commander Valery Zaluzhny was first to announce the operation on June 30. Details were later widely confirmed by independent news platforms and Ukrainian officials, including a Joint Forces South officer in comments to Kyiv Post.

“The Ukrainian armed forces have proven to be extremely good at learning and adapting quickly. This might seem natural, but it’s actually a rare trait in many armies, including some in NATO who are stuck in outdated doctrine and dogma,” said Wes O’Donnell, a Michigan-based security analyst and military writer.

“Ukraine has proven the power of battlefield improvisation and willingness to experiment with new technologies and tactics on the fly. It’s a very entrepreneurial mindset, actually. Move fast, try new things, discard what doesn’t work, and adopt what does,” O’Donnell said.

That’s not to say that everything worked according to plan in the Zmiinyi bombardment. Plenty went wrong. The weapons used – a 28-ton Ukraine-made Bohdana howitzer and a 17-ton French-made Caesar howitzer – repeatedly got stuck, and at times threatened to tip over on their sides while driving on or off the barge.

NATO-standard 155mm guns, it turned out, weren’t designed for hundreds of shots at absolute maximum charge. Sealing rings failed. Barrels got too hot and needed to cool. Rifling wore out. All that affected shot accuracy, causing more problems.

In July 14 television comments on the Orestokratiya news program, Myroslav Hai, a participant in the operation, said Ukrainian gunners discovered that the NATO shells – cleverly designed to explode over a target for maximum damage – were almost impossible to see if they blew up over water. That made shifting fire difficult.

Even if a drone operator actually saw the shell detonate and wanted to make a correction, the firing data had to pass through a least two staff officers watching their own video of the shelling, and those two were fully capable of ordering the wrong correction.

However, persistence, a nuanced attitude toward instructions from a ranking officer, and a common will to hit the Russians helped overcome those glitches, the reports said.

The first major Ukrainian artillery victory, also heavily improvised, came in the first days of the war, when Russian paratroopers attempting to capture Hostomel airfield to the north of Kyiv found that their drop zone was under the guns of an AFU howitzer brigade that happened to be nearby.

Working with civilian volunteers in territorial defense units with zero artillery training, but an excellent knowledge of local terrain, the Ukrainian guns wrecked the elite Russian infantry formations in about a week.

A Ukrainian serviceman of an artillery unit throws an empty shell as they fire towards Russian positions on the outskirts of Bakhmut, eastern Ukraine in December. PHOTO: AFP

A Ukrainian serviceman of an artillery unit throws an empty shell as they fire towards Russian positions on the outskirts of Bakhmut, eastern Ukraine in December. PHOTO: AFP

Early successes like Hostomel and plummeting shell stocks (Ukrainian gunners fire fast, and in a week of hard fighting can shoot off about twice the 155mm shells America currently manufactures in a year) helped convince the U.S. and NATO, in late March, to send the first Western artillery pieces to Ukraine, a towed U.S.-British gun called an M777.

By almost any peacetime standard, asking Ukrainian artillerymen to learn a new gun system and then use it in the field, in matter of weeks, was silly.

In early May, Ukrainian gunners operating 60 to 80 M777 cannon rushed to the front brought Russia’s last full-on combined arms operation of the war to a bloody halt – a failed operation that attempted to throw assault bridges over the Donets River, in the eastern Donbas sector.

“The Americans gave us the tools and we did the work,” Serhiy*, an artillery officer present at the May battles, told Kyiv Post in a January interview on one of the battlefields.

“We put up a wall of fire, they would try another crossing, and we put up a new wall of fire there.”

“As soon as the [Western] realization came that Ukraine can basically resist and as soon as it became clear that the use by Ukraine of test batches of NATO artillery are basically effective, supplies became large-scale,” said Oleh Izhak, head of the regional and community research department at the National Institute for Strategic Studies.

“The question of provoking Russia here seems to have been secondary.” The HIMARS and associated M270 precision-guided missile systems started reaching Ukrainian hands in significant numbers in June.

They proceeded to devastate Russian ammunition depots and headquarters. According to unconfirmed reports and accounts from officers of the 107 th Rocket Artillery Brigade to Kyiv Post, they even killed at least three senior Russian generals.

Currently, Kyiv is making the case to Washington that the Ukrainian artillery can be trusted with even longer-range missiles and other advanced military kit. At the now-in-progress Battle of Vuhledar, according to social media videos, an account to Kyiv Post by an officer serving with a firing unit, and published accounts by Russian prisoners of war, Ukrainian gunners are widely using high-tech Western artillery-delivered mines to ambush attacking Moscow troops.

Other innovations fielded by the Ukrainian artillery over the last 12 months include: widespread use of crowd-sourced fire control software, dispersal of individual guns twice and even three times farther apart than specified in NATO doctrine, linking of video feeds from crowd-sourced drones to fire control centers, and gunner training programs that last six months in NATO armies reduced to eight weeks.

But international observers, AFU service personnel and independent Ukrainians all agreed that the critical ingredient for Ukrainian artillery prosperity in the future is, without question, simply enough shells to shoot at the Russians.

A Ukrainian serviceman of the artillery unit of the 80th Air Assault Brigade strokes a stray dog near Bakhmut on Feb. 7, 2023. PHOTO: AFP

A Ukrainian serviceman of the artillery unit of the 80th Air Assault Brigade strokes a stray dog near Bakhmut on Feb. 7, 2023. PHOTO: AFP

About four out of five of all rounds fired by the AFU are now NATO standard. Whether the Ukrainian military will prevail in combat depends directly on how many hundreds of thousands of NATO-standard howitzer shells the AFU gets from its allies, and how fast, they said.

“Just like in the First World War, logistics worked in the Second World War. Whoever has a larger supply of resources wins,” said Colonel Oleh Faydiuk, commander of the 45 th Separate Artillery Brigade, in a Feb. 7 Ukrainska Pravda interview.

He said he was confident that, given enough ammo, his gunners would stop all Russian attacks and ultimately win the war. “I like to say that when this war is over, Ukrainian gunners will be teaching classes at West Point,” O’Donnell said.

*Surname not made public per AFU service member request

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter