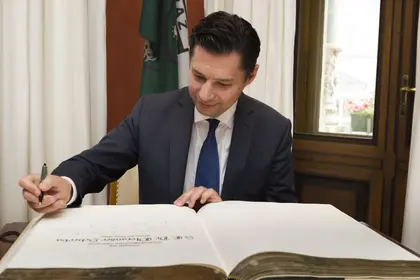

Olexander Scherba is a Ukrainian diplomat and author who served as Ambassador to Austria from 2014 to 2021. Based upon the years that Ambassador Scherba spent working on Ukrainian – European relations, Dr. Scherba sat down with the Kyiv Post to discuss how Germany and Austria’s reluctance to assist Ukraine can best be understood.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Mr. Ambassador, could you tell us a bit about your background, and what you are doing now?

It’s simple, really. I’ve spent most of my life in Ukrainian diplomacy. Overall, 27 years – with short leaves of absence in 2009, 2013 and 2022. The last one was as a consultant for NAK Naftogaz, Ukraine’s main oil and gas producer. Since December, I have been ambassador-at-large at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in charge, among other things, of Crimea’s de-occupation portfolio. My last position abroad was Ambassador to Austria in 2014-2021.

Austria, like Germany and Switzerland, has been more reluctant to give Ukraine the robust support that other countries have. Why is that?

Austria is a country that takes the idea of neutrality very seriously. Even its national holiday is not an Independence Day, as with most of countries, but the day of declaration of neutrality.

Many Austrians believe neutrality is the secret of happiness: we are a small country; we do not bother you, you do not bother us. An Austrian friend told me once: Austrians disagree over everything aside from three things. First, they don’t want nuclear energy; second, they don’t want genetically modified stuff in their food; and third, they don’t want NATO.

Accidental Ukrainians: The Russian Invasion Through American Eyes

Hence, Austria’s reluctance to participate in any kind of military support or a conflict, especially with the word “NATO” in it. But when it comes to non-military help, I think Ukraine has plenty to be grateful for. Just look how many Ukrainians have found refuge in Austria, let alone Germany.

Why do you think that Russia has been so effective in penetrating popular political thought in the Germanic countries? (Or why has Ukraine not been as successful?)

I don’t think Germanic nations are psychologically more susceptible to Russian narratives than others. According to most sociological surveys, this region is more in the European mainstream than in [Russian President] Vladimir Putin’s corner. But, since Germany is so influential, all eyes are on it.

Plus, there’s a whole array of factors that make the situation in this part of Europe special. Beginning with history. A – Germany and Austria have a historic sense of guilt since World War II. Paradoxically, not to Ukraine that was fully destroyed by the Nazis, but to Russia.

B - Russia is historically familiar both to Germany and Austria, whereas Ukraine isn’t (Austria knows Galicia and Bukowyna as former territories, but not Ukraine as such).

C – Both Germany and Austria are a mixture of their imperial past and the post-WWII history, heavily influenced by social-democratic ideas. Russia too is a mixture of an imperial past and leftist present.

But it can’t be only about history, can it?

Of course not. The economy is a huge factor, too – there has been said so much about it. But there’s also another important thing that often gets overlooked.

In the post-Soviet time, Europe’s newest history was developing as a formation of two circles, two worlds, if you want: the European Union on the one side, and Russia’s zone of influence on the other. So, to say, “the Russian world”, less free or unfree, but still a legitimate part of European identity. For most Europeans this division seemed logical or at least, historical.

In European perceptions, these two European circles – the free and unfree – were at some point to be completed and interlink for mutual benefit, even bigger than in Europe’s golden time, the 1990s and 2000s. It was in that moment when the 2014 Euromaidan happened. Ukraine defied historic odds and refused to be in Putin’s corner of the continent.

Because of our desire to be free, the EU’s vision for the near future went topsy turvy. We broke Russia’s imperial plans and stood in the way of the EU’s growth spurt, propped up on the resources of the “Russian world”. Hence, Russia’s fury on the one hand and the “Ukraine confusion” of many EU nations on the other.

European history changed with the Euromaidan and the annexation of Crimea in 2014 – not the way Europe planned. And even more so when Ukraine didn’t obey Putin’s Hitler-like invasion in 2022.

Ok, what changed in 2022?

Europe in particular, and the West in general, woke up. The pictures of Russia’s invasion were not only brutal, but too reminiscent of things that were happening on the European continent 84 years ago.

It became too obvious that Putin’s Russia was not a different kind of Europe, but the reincarnation of Europe’s worst fears and memories. This emotional wake-up call is what is holding the pro-Ukraine coalition in Europe together. This – and the realization of most politicians in charge that unlike their predecessors, they’ll be judged not only by voters, but primarily by history. After a leave of absence for a couple of decades, history is back now as a factor of political decision-making.

Knowing European diplomacy, how realistic is it that Europe will stay united behind Ukraine? What should be done to achieve that? What must be avoided? What are the risks and opportunities, etc.?

I think Europe will stay united. The shock of a Hitler-like war on the continent and the insult of being duped by Putin for decades is too deep for most Europeans. They won’t be duped again. As much as many in Europe want this nightmare to end (even at the cost of Ukraine’s interests), they aren’t in the driving seat on this issue. Ukraine is.

And if Ukraine doesn’t give up, Europe can’t afford to give up either. Supporting Ukraine but caving in when push comes to shove – that would be morally unjustifiable and, I think, politically unsellable.

What needs to be done on Ukraine’s part is to stay brave and fighting. What needs to be avoided on our part is appearing ungrateful. Europe feels Ukraine’s pain – Ukraine should feel the pain of Europe, too. Putin wages a war on us both, we both pay the price. The fact that our price is much higher, doesn’t mean that we may take the patience of average Europeans for granted.

You have known Russian diplomats in your career. The world sees them and hears their remarks about Ukrainian Nazis, "liberation" of cities, etc., and it is almost impossible for a Westerner to believe that they are serious: Were their diplomats always like this? Is the Russian Foreign Ministry a bunch of radical extremists, or is it that they have been so brainwashed?

No and no. They understand everything. They’re just cowards who choose to play by Putin’s rules and see Russia’s future go down the drain instead of standing up and voicing their protest. I always saw diplomatic service as a kind of international group of people “on a mission from god”: making this world less insane. Well, Russian diplomats proved me wrong. They turned out to be nothing but obedient boot-lickers to Putin.

You have published a book, Ukraine vs Darkness: Undiplomatic thoughts, which really gets down to exactly what is happening today with Russia's invasion – could you tell us a bit about it?

Aside from being a diplomat, I have been a columnist for one of Ukraine’s central newspapers. In 2019, my essays were published as a book, and recognized by Ukraine’s PEN-club as one of the top books of the year. Someone offered to translate it into English. And since, because of the pandemic, I had more than usual free time on my hands, I agreed.

But I didn’t like how the book sounded in English. So, I started re-writing and adding one chapter after another. In the end, I had a new book that was written in English and was serving a new purpose: explaining Ukraine to the West. And the title turned out almost prophetic: “Ukraine vs. Darkness” – meaning the global darkness, the darkness of dictators getting bold, pushing on, and freedom not believing in itself anymore. The darkness of putinism, trumpism, the post-truth world – and of Ukraine’s own sins.

If there was one take-away, that you would want a reader to get from reading your book – what would it be?

Value freedom because it can be gone sooner than you think. And embrace the fact that sometimes freedom can sprout through layers of bad history in the most unusual places. Like it did in Ukraine.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter