When Taras Gren, a Ukrainian Army colonel, was ousting Russian-backed separatists from Popasna, an eastern city 740 kilometers away from Kyiv back in 2014, he had been expecting the locals to be grateful for their liberation.

What he got was very different from gratitude. To his surprise, an elderly woman from the city attacked him in the street.

“She started swearing at me, beating me, calling me a murderer, a punisher. She even spat at me,” Gren said.

The woman, Gren thinks, was one of the many residents of the Donbas that have been influenced by Russian propaganda. After three years of Russia’s war in the Donbas, Ukraine continues to fight the aggressor on all fronts.

The Russian-led forces that have seized control from the government in parts of the Donbas are reinforcing their positions with propaganda spread via local TV and radio.

Through the propaganda, the Kremlin is pushing its false narrative that the annexation of Crimea, which was followed by the war in eastern Ukraine, was an effort to save Russian-speaking Ukrainians from threats coming from the Ukrainian government.

The same propaganda still fuels a deadly war that has claimed the lives of more than 10,000 people in the last three years. Compared to Russia, Ukraine is allocating very little money to countering the enemy’s information war.

In 2017, Russia allocated $1.2 billion to government-owned media. Ukraine provided just $76 million in funding for state-owned media and the Information Ministry together.

The difference is even bigger than between the two countries’ defense budgets: Russia spends $47 billion on defense, while Ukraine allocates $5 billion.

TV battles

When in early April 2014, Russian-backed separatists seized a number of cities in eastern Ukraine, they also took over a number of TV towers, including the 360-meter one in Donetsk, which provides a signal to the whole oblast.

The separatists switched off Ukrainian TV channels and replaced them with Russian ones, including state-owned Rossiya 24 and Rossiya 1, known for their inaccurate news reports about the war in Ukraine.

Soon, separatists started broadcasting their own news on the channels Novorossia TV, Oplot, and DNRNews, which they launched using the equipment of existing local Donetsk stations. These, and over 25 Russian TV stations make up the TV diet for most of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts, including Ukrainian-controlled territories near the front line.

Kyiv has been struggling to make Ukrainian TV accessible in the region again. “We can’t build the trustful communication with the Ukrainian citizens in the occupied Donbas and Crimea without the renewal of Ukrainian broadcasting on those territories,” Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko said in November.

Ukrainian TV in the occupied territories can be accessed only through a satellite dish or Internet streaming.

But these ways require payment, while many Ukrainians are used to watching TV for free, according to National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council of Ukraine member Serhii Kostynskyi.

“They still prefer to watch the free TV, which they can access with a TV antenna,” Kostynskyi said.

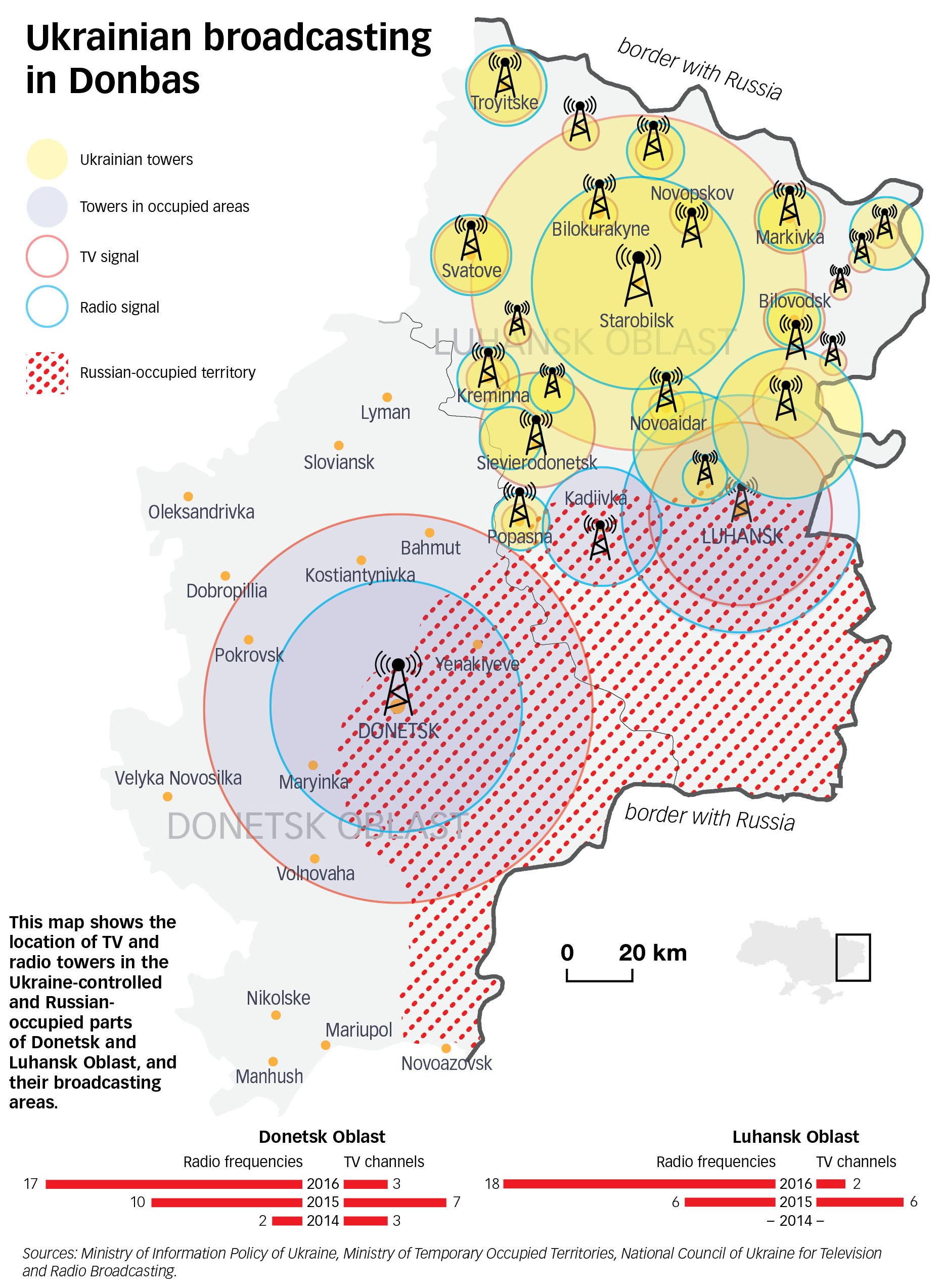

This free TV is broadcasted via TV towers. With the biggest tower in Donbas controlled by the separatists and some smaller ones destroyed in the fighting, Ukrainian TV is broadcasted through 10 smaller towers: five in Luhansk Oblast, and five in Donetsk Oblast.

The Ukrainian-controlled TV towers in the Donbas can broadcast a signal for 20–100 kilometers, which leaves many blind spots in the two oblasts, which have a combined area of around 50,000 square kilometers.

The signals of Ukrainian-controlled towers don’t reach the occupied territories at all, and they barely even reach the front line, leaving even Ukrainian soldiers exposed to Russian TV propaganda.

Volodymyr Nykonenko, who served with the Ukrainian Nationalist Battalion in 2015, said that on the front line the soldiers often had to watch Russian TV channels, including the notorious Zvezda and First Channel, because it was almost impossible to get Ukrainian TV.

“Russian TV often showed how the separatists’ army is unbeatable and Ukrainians are doomed,” Nykonenko said.

To bring Ukrainian TV to the soldiers, the Defense Ministry purchased 200 satellite dishes to be used on the front lines.

But according to Kostynskyi, few of these are left there today — soldiers have been taking them home when their service ended.

However, Gren said that in his experience, Ukrainian soldiers don’t take Russian TV propaganda seriously. In fact, they still use classic Russian propaganda fakes as a source of humor.

For instance, Russian TV news once featured a fake report about school teachers in Ukraine forcing students to kill bullfinches because their white-blue-red coloration was reminiscent of the Russian tricolor.

Now, according to Gren, Ukrainian soldiers like to joke that they have nothing to eat because “bullfinch supplies are running low.”

But many civilians in Donbas don’t find these TV reports funny — or fake.

Showing progress

Ukrainian authorities made some progress in bringing Ukrainian television back to the Donbas since the region nearly lost it in 2014.

Three new TV towers were built in the Donbas, funded by private donations and local councils, to cover blind spots in Ukrainian-controlled territories and Crimea.

One of the new towers even reaches the northern part of the annexed Crimea. Still, all of the Ukrainian towers are smaller than 200 meters, which means the 360-meter TV tower in separatist-controlled Donetsk can override their signal.

To encourage Ukrainian TV and radio stations to broadcast in the Donbas, the National TV Council allows them to broadcast there without a license, which takes up to one year to get.

In early 2016, the new radio station Army FM was launched for Ukrainian soldiers based in Donbas. But it also covers many cities close to the front line, providing the civilians with an alternative to Russian and separatist radio stations transmitted via the Donetsk broadcasting tower.

The government is also working to block anti-Ukrainian broadcasting. In 2014, Ukraine blocked 14 Russian television channels from its cable networks, accusing them of spreading war-related propaganda. In 2016, three more were banned.

At the same time, Ukraine is trying to jam the Russian TV signal in Donbas. The first jamming system was tested on Aug. 3 in the Ukrainian-controlled city of Pokrovsk (formerly called Krasnoarmeisk), 537 kilometers southeast of Kyiv, according to Head of the National Security and Defense Council Oleksandr Turchynov.

It would take up to four months for the jamming system to start working. However, the authorities don’t reveal how much of the territory of Donbas will lose access to Russian and separatist TV after the system is launched.

Critical media

Even so, Ukraine is still losing to Russia in the information war, Kostynskyi says. In his view, the reason is that the Russian media, almost all of which is state-controlled, stick strictly to a single narrative.

“While channel-surfing, viewers hear the same message: (Russian President Vladimir) Putin is the best, everything’s fine in Russia, we are not afraid of sanctions… Russian media create a fake reality,” Kostynskyi says.

On the other hand, he says, the media in Ukraine keep the population in constant stress, reporting on stalled reforms, corruption, and economic problems.

However, Kostynskyi believes that even though criticism in Ukrainian media is undermining people’s trust in the authorities, strategically, it is a good thing.

“If we used the same propaganda tactics as in Russia, saying everything’s fine, we wouldn’t have any progress,” Kostynskyi said.

“Clever social policies and better standards of living, not ideological propaganda, will reintegrate the Donbas and Crimea with Ukraine.”

Kremlin-backed fighters muzzle media in Donbas, expert says

Despite Ukraine’s efforts to win the hearts and minds of people in the occupied territories of Donbas by improving access to Ukrainian broadcasting, the majority of the population in the occupied territories are not receptive to Kyiv’s message, according to experts.

At least 2.7 million Ukrainians still live in the occupied territories in the Donbas, says Dmytro Tkachenko, who heads the Donbas Think Tank analytical center, and some 44 percent of them see the current situation in eastern Ukraine as a civil war.

Tkachenko says the residents of the occupied Donbas fear returning to government control, and they mostly share the values and mode of thinking of people living in Russia, rather than residents of other regions of Ukraine. This is according to the findings of the latest report on the mindset and identity of the residents of controlled and uncontrolled territories of the Donetsk region, which was prepared by the Donbas Think Tank.

At least 44 percent of those who live in the territories controlled by Kremlin-backed fighters think the freedom of speech conditions are there better than in the rest of Ukraine. The number of respondents who think that the freedom of speech is better protected in Ukraine is four times less, at some 11 percent.

Local media have a lot to do with this, according to Tkachenko, who is also an advisor to Ukraine’s minister of information policy. Tkachenko’s main points on conditions for freedom of speech and local media in the occupied part of Donetsk Oblast are as follows:

Propaganda

Kremlin pre-election propaganda tactics are being used – the main principle is to drown out all competing voices. Russian-led forces in the occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblast are applying the same tactics.

Local media

The Kremlin’s proxy forces have taken control of the entire local media market apart from Moskovsky Komsomolets Donbas – a local branch of the Moscow-based daily newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets, which was founded in 1919. Even so, the newspaper is hardly functioning, as the editorial team has mostly left.

At the same time, since December 2014, the Russian-led occupiers have started publishing the Russian newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda every day. Yevgeni Sazonov, the deputy chief editor of Komsomolskaya Pravda in Moscow, oversees this. Allegedly, the budget for the publication in the Donbas is about 2 million rubles per month. Its content varies greatly from its Kyiv and Moscow versions.

There are two main trends in news coverage: the first is exclusively positive headlines for domestic events, and the second very negative reporting about anything connected to Ukraine.

There are about 20 newspapers, four TV channels and six radio stations in the Donbas now under total control of the occupation authorities. All of the papers from the two regional print houses in occupied Donetsk Oblast are sent to the servers of the so-called ministry information for censorship.

Ihor Antipov, former head of Donetsk branch of Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper and now the acting minister of information, is responsible for censoring media coverage in the region. A story can be killed at any time. For example, on Aug. 9 an article on the Malorossiya project (a scheme to take over the who of Ukraine and rename it Malorossiya, or “Lesser Russia,” was killed when the leader of the Russian-backed occupying forces in Donetsk, Oleksandr Zakharchenko, announced the abandonment of the Malorossiya project, saying that many people didn’t accept it.

Information blocks

More than 100 websites have been blocked in the occupied territories. The blocks were first introduced in 2014, and the list of banned websites is updated regularly. All Ukrainian TV channels and radio stations are also banned. The only exception is Ukrainian broadcasts of Shakhtar FC soccer games – but often without sound, so that the football fans’ famous obscene chant “Putin is khuilo (dickhead),” cannot be heard.

Dmitry Kiselyov, a Russian TV host notorious for his distorted coverage of Ukraine and the West. (AFP)

Pushing fake narratives

Even before 2014, Russian media tried to control more of the Ukrainian story: They have portrayed the EuroMaidan Revolution as an opportunistic coup enabled by Ukrainian nationalists and neo-Nazis. This narrative had prepared the basis for the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas in 2014.

By spreading half-truths and rumors through state-owned media, the Kremlin often showed its own version of the events enacting propaganda on the ground.

In 2015, state-owned Rossiya-1 TV channel aired a three-hour documentary called “Crimea: Path to the Motherland” in which Russian President Vladimir Putin said while discussing sending troops to Crimea that “…the nationalists would have killed those people,” referring to the Russian-speaking people in Crimea.

Probably the most notorious fake report that aired on Russian state-owned TV was a news report in which a Donbas woman said that she saw Ukrainian soldiers crucifying a three-year-old boy whose parents were supporting separatism. The report was debunked and the woman identified as an impostor, but that didn’t stop more fake stories like that from airing.

Another famous news report said that every Ukrainian soldier fighting in Donbas was promised to be given two Donbas civilians as personal slaves after the war was over.

In 2014, Rossiya-24 journalist Alyona Kochkina said on Facebook that young Ukrainians who travel by trains and buses are being captured and forcefully sent to serve in Ukraine’s National Guard. On a different state-owned station, Rossiya-1, a talk show participant claimed that Ukrainian soldiers raped a 47-year-old woman suffering from epilepsy in Kramatorsk in Donetsk Oblast. All the reports were proven fake.

Zvezda TV channel once reported that Kyiv authorities banned traditional New Year symbols Father Frost and Sniguronka as part of decommunization.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter