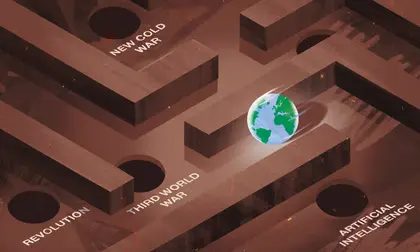

In these times of planetary polycrisis, we try to get our bearings by looking to the past. Are we perhaps in The New Cold War, as Robin Niblett, the former director of the foreign affairs thinktank Chatham House, proposes in a new book? Is this bringing us towards the brink of a third world war, as the historian Niall Ferguson has argued? Or, as I have found myself suggesting on occasion, is the world beginning to resemble the late 19th-century Europe of competing empires and great powers writ large?

Another way of trying to put our travails into historically comprehensible shape is to label them as an “age of …”, with the words that follow suggesting either a parallel with or a sharp contrast to an earlier age. So the CNN foreign affairs guru Fareed Zakaria suggests in his latest book that we are in a new Age of Revolutions, meaning that we can learn something from the French, Industrial and American revolutions.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Or is it rather The Age of the Strongman, as proposed by the Financial Times foreign affairs commentator Gideon Rachman? No, it’s The Age of Unpeace, says Mark Leonard, the director of the European Council on Foreign Relations, since “connectivity causes conflict”.

But come now, surely it’s The Age of AI, the title of a book co-authored by the late doyen of foreign affairs gurus, Henry Kissinger. Or “the age of danger”, as international essayist Bruno Maçães argues in a recent issue of the New Statesman? If you type the words “the age of …” into the search box on the website of the journal Foreign Affairs, you get another bunch of contenders, including the age(s) of amorality, energy insecurity, impunity, America first, great-power distraction and climate disaster.

Perhaps this is just the age of hype, in which book publishers and media editors relentlessly drive authors towards big, dramatic, oversimplifying titles for the sake of sales impact in an overcrowded marketplace of ideas?

Joking apart, it’s vital to try to learn from history since, as Evelyn Waugh, that master of precise English prose, writes in Brideshead Revisited: “We possess nothing certainly except the past.” The trick is to know how to read it.

First, you need to identify the mix of old and new, similar and different. The relationship between the only two current superpowers, the US and China, clearly is, as the US secretary of state, Antony Blinken, put it during a recent visit to Beijing, “one of the world’s most consequential relationships.” As during the cold war, these two superpowers have a global, multi-dimensional, ideologically inflected, long-term strategic competition.

Yet as Niblett rightly observes at the very beginning of his book: “The New Cold War will be nothing like the last one.” He singles out two big differences: the degree of economic integration between the two countries, which in the past has led pundits to talk of Chimerica; and the fact that this contest is “far less binary” because there are so many other great and middle powers, such as Russia, India, Japan, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Brazil.

The first point is clearly significant, but won’t necessarily prevent a cold war turning hot. Just a few years before the First World War broke out, the journalist Norman Angell published an influential book called The Great Illusion. He argued that the degree of economic interdependence between the European great powers meant that a big interstate war was highly unlikely – and couldn’t last long anyway. It was Angell’s own thesis that turned out to be the great illusion.

Niblett’s second difference seems to me compelling. Sometimes these other powers are described as the new non-aligned – another term from the cold war period – but they are much richer and more powerful than the pre-1989 non-aligned nations. As we see over the war in Ukraine, Russia’s relationships with countries like China and India enable the Russian economy to survive everything the west can throw at it.

In another attempt to give an overall label to this age of confusion, political scientist Ivan Krastev, Mark Leonard and I have posited an “à la carte world,” in which non-western great and middle powers make transactional alliances, sometimes simultaneously aligning with different partners in different dimensions of power. For example, they combine a major economic relationship with China and a security relationship with the United States.

This analysis cuts against the notion of a more fixed new “axis of authoritarianism” between China, Russia, Iran and North Korea. Here the very word axis implies something like a wartime alliance, since it echoes not just the “axis of evil” identified by US president George W Bush but also the original Axis of Nazi Germany, fascist Italy and imperial Japan in the second world war. “And now, as in the 1930s,” Ferguson wrote earlier this year in the Daily Mail, “a menacing authoritarian Axis has emerged …”

Learning from the past also involves seeing the interaction between deep structures and processes, on the one hand, and contingency, conjuncture, collective will and individual leadership on the other.

Our time offers important examples of both kinds of historical force. The way in which the accumulation of the unintended effect of human activities is dangerously transforming our natural environment, through global heating, the reduction of biodiversity and resource scarcity, is one of those deep structural changes. Hence the characterisation of our age as the Anthropocene.

The accelerating development of technology, including AI, is another structural change. Kissinger argued that inherently unpredictable military applications of AI might eventually undermine even the minimal strategic stability of nuclear deterrence between the US, China and Russia.

But if you ever doubt that contingency and individual human choices matter as well, you need look no further back than February 2022, when Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s inspiring personal leadership, and the way that Ukrainian forces just managed to deny the Russians control of Hostomel airport, changed the course of history.

This goes to the last and most important point. The interpretive cacophony that I’ve identified is itself symptomatic of the fact that we are in a new period of European and global history, with everyone casting around for new bearings.

The postwar period (after 1945) was followed by the post-Wall period, but that lasted only from 9 November 1989 (the fall of the Berlin Wall) until 24 February 2022 (Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine). In history, as in romance, beginnings matter. What was done in the five years after 1945 shaped the international order for the next 40 years – and in some respects, such as the structure of the UN, to this day.

So what we do now, for example in enabling Ukraine to win or allowing it to lose, will be crucial in determining the character of the new era. History’s most important lesson is that it’s up to us to make it.

Timothy Garton Ash’s Homelands: A Personal History of Europe was recently awarded the Lionel Gelber Prize.

This article appeared in The Guardian on May 3, 2024, and is reprinted with the author’s permission. See the original here.

The views expressed in this opinion article are the author’s and not necessarily those of Kyiv Post.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter