As my plane descends into Istanbul airport, from the window I scan the horizon towards the direction of Ukraine, now a warzone. It is 24 February 2022.

While I travel to Zahle in Lebanon to meet one Maria, to bring her medicine and money to keep her alive, I perform the fatiha prayer for another Maria, my friend in Kyiv, to be protected and kept alive.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

I make a nidhr, a promise to Sayyida Khawla, the deceased daughter of our revered Imam Hussein that I will visit her shrine in the neighboring Lebanese town of Baalbek, if Ukrainian Maria survives.

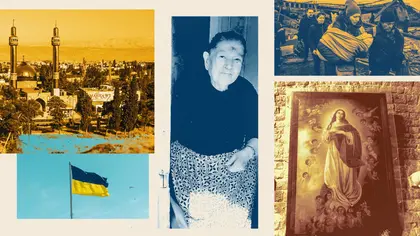

The Maria I am visiting is my grandmother’s older sister, whose family were refugees after World War I, leaving Mardin, in today’s Turkey, to Lebanon. While I was on the plane moving east, I knew Maria in Kyiv was a refugee in the making, and that she would eventually flee to the west.

This tale of two Marias is one of the greater Mediterranean, the sea in the “Middle of the Earth,” flowing into the Black and Red Seas and the terrain surrounding them.

These lands and waters which have witnessed waves of refugees, due to conflicts which compel and coerce. A history of displacement over distance, from antiquity’s Sea Peoples to Syrian refugees.

On Thursday, Feb. 24, 2022, both Maria Marchenko and I are preparing for trips to or away from an airport.

At 5 a.m. Maria Marchenko is jolted from her sleep. A barrage of ballistic missiles bombarded Kyiv airport, close to where she lives. Airports around the capital city were targeted that day to prevent Ukrainian planes from taking off, while Moscow sought to secure them as staging grounds for the assault on the capital.

At the same time, it is 6 a.m. in Madrid. I am packing for my trip to Lebanon in a few hours to visit Maria Shakir, delivering her the pain reliever Panadol and US dollars, both in short supply there due to an economic crisis.

Istanbul, where I am making my transit, is relatively close to the war zone and I wonder if flights might be cancelled. That would devastate Lebanese Maria. She is 98 and hasn’t seen me in 13 years.

While I’m packing my bag the morning of my flight because I am a procrastinator, Maria hadn’t packed because she did not believe that war would erupt. She thought if she did pack her bag in advance for such a scenario, war would then inevitably occur.

I had prepared my Madrid apartment for Maria, her mother and father in case they needed to flee here. I had arranged fresh linens for them, turning my apartment into a haven to accommodate three potential refugees.

During the morning of the 24th both Maria and I pack warm clothing. There is a winter storm in Zahle, in the high mountains of Lebanon. Maria will be going to a bomb shelter, well below the ground in a freezing metro station.

We collect our documents, laptops, and chargers. Maria packs something I have no need to: photos of family and friends, to preserve their memories unsure if she would see them again.

I shut the teal window blinds on my balcony. On top of the entrance to the convent in front of my house, a dove representing the Holy Spirit flies above the representation of Mary. For her namesake in Ukraine, it is not a dove that flies above her head, but rather enemy aircraft.

Driving to the airport, I dial Maria in vain. The first leg of my journey is to Istanbul, a four-hour journey where I won’t be able to make calls. At this point, I am not sure if the telecommunication lines have been hit, or even if Maria is still alive.

As I am about to board the plane and turn off my phone, she picks up. When I ask about her, she holds back her tears. Her parents live in Okhtyrka, in the Sumy region, 30 miles from the border and now the front lines. Nonetheless, she declares her wish for peace, with no malice or cynicism in her voice. I remind her that they have a home in Madrid.

I place my KN-94 mask snuggly on. And a surgical mask on top of that. I am so grateful the seat next to me is empty. I have yet to catch Covid and feared how I would fare with this virus in Lebanon, having heard stories about the abysmal conditions of health care as a result of the economic crisis. My grandfather survived a pandemic by moving to Lebanon in the late 1940s. I do not want to repeat history.

For the next four hours I will be dodging viruses. I fret that this plane will also have to dodge missiles as we approach Istanbul airport, close to the Black Sea, where warships are bombarding Ukraine with cruise missiles, according to the news.

Istanbul airport is unusually empty. I look at the screen for the gate to my connecting flight to Lebanon, noticing a list of cancelled flights that were destined for Ukraine and Russia.

Maria Shakir's apartment in Zahle, Lebanon. [Ibrahim al-Marashi/TNA]

I turn on my phone. No messages from Ukrainian Maria, but Lebanese Maria sends me pictures of the dishes she has prepared for my arrival via Whatsapp – hummus with olive oil and sesame seeds and falafel.

She is 98-years old yet knows how to send gifs and emojis. When I confirm I am boarding the plane, she sends a gif of a woman from the sixties with a bra that fires sparks, like bullets. When I leave her a voice message that the flight to Lebanon is scheduled to leave on time, she sends me an animated image of Jesus Christ.

Five hours later, drenched and exhausted, I arrived at a first-floor apartment in Zahle. Maria is elated. I collapse on her sofa. She hugs me, and screams “tu’burni” or “you will bury me,” which is a term of endearment, but I dread the thought of her passing. She is so short that even sitting on the sofa our eyeline is equal.

While she prepares the food, I recline on the sofa, made out of a wooden frame, yet the cushions are made with thick grey blankets, stamped with the logo of “UNHCR,” the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, while a stuffed teddy bear and cheetah rest behind me.

I am too embarrassed to ask whether her or a resourceful furniture maker had reappropriated them from the nearby camps housing Syrian refugees.

She brings out her folded table and I eat right there.

“My Maria in Zahle frets when she learns that the grain supply from Ukraine will be interrupted, increasing the price of bread in Lebanon. It’s fortunate I have arrived with US dollars to help her adjust to this crisis.”

While I am in the most comfortable setting, my second home, Ukrainian Maria’s second home is underneath the earth, a cold, underground bomb shelter. While I have a sumptuous Lebanese feast, Maria in Kyiv occasionally comes up for air, to find soup during the ephemeral lull of security, until the sirens call her back.

I asked Maria in Zahle to turn on the TV so I can find news about Maria in Kyiv. My Maria in Zahle frets when she learns that the grain supply from Ukraine will be interrupted, increasing the price of bread in Lebanon. It’s fortunate I have arrived with US dollars to help her adjust to this crisis.

On top of the TV set, on the wooden bookshelf, there are three separate depictions of the Virgin Mary and a drawn image of Jesus holding his hand to his heart, while what seems like laser rays of red and blue are coming out of his chest.

During the late 1940s, my grandfather contracted tuberculosis, the Covid-19 of its time. He had to leave his home, Najaf, in the dusty Iraqi desert to recover in the clean mountain air of Zahle. He probably bemoaned his fate, but there he met my grandmother, a Christian refugee from Mardin.

If it were not for refugees and pandemics my mother would not be born, and I would not exist.

I often question why God let my grandmother die at such a young age, when my mom was barely five years old. For most of my life I did not know Maria Shakir even existed. It was only as an adult I travelled to Zahle trying to find my grandmother’s family, eventually finding Maria.

Maria and my entire grandmother’s family are Syriac Orthodox Christian. The country of Lebanon tore itself apart because its Muslims and Christians could not see what unites them, and instead focused on the narcissism of small differences, plunging the country into a civil war that lasted from 1975 to 1991.

Yet this Shi’a Muslim flew across the Mediterranean to help his Christian great-aunt, bringing her money, medicine, and his love.

But in Ukraine that same day, the invaders that day could only focus on hate, in their minds, dark, vacuous caverns where only enmity and evil exist, and another set of small differences. Maria in Ukraine became another victim in this cycle.

On the other wall by the TV was an image of Mar Elias Shakir III etched in silver. The Patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox church. Maria’s uncle. My great-uncle. I make another nidhr to him: “If you help Maria, she is Orthodox like you, get out of Ukraine safely, I will visit your shrine in Kerala, India.”

Ibrahim al-Marashi with Maria Marchenko in Milan, Italy. [Ibrahim al-Marashi/TNA]

During dinner, when I tell my great-aunt Maria about my visit to the shrine of Sayyida Khawla, she informs me that Our Lady of Bechouat, the site of a Marian apparition, is only ten minutes away from Baalbek.

She tells me this, not to pay a visit as a pilgrim. In fact, rarely do our religious differences ever come up in conversation. My aunt Maria also worships another religion: gastronomy.

She tells me that a woman in Bechouat has a café next to the Marian shrine and where I could eat saj, a Lebanese flat bread cooked on an open circular grill, complemented with thyme or cheese. Of course, her saj is not as good as Maria’s, she reminds me, but I should try it still since I will need to eat lunch.

On Friday, the Muslim day of prayer, I arrive at the Sayyida Khawla shrine. I approach the shrine, with a gilded minaret and dome, interspersed with turquoise ceramic tiles and white Arabic calligraphy. I pass a pointed arch and enter the main hall, and look up at the dome, a pattern of the top in the shape of a star, a representation of heaven in perfect geometrical symmetry.

Not a single space is unadorned, illuminated with beams of light, with walls and ceilings made up of alternating panels of gold and silver, shimmering, shining, sparkling, with crystals glittering, glimmering, mesmerising.

“Rarely do our religious differences ever come up in conversation. My aunt Maria also worships another religion: gastronomy.”

I approach the above ground tomb. Khawla was another person displaced by conflict, a refugee of sorts, more akin to a prisoner of war. Khawla was the daughter of Imam Hussein and great granddaughter of Prophet Muhammad. Hussein, the prophet’s son-in-law, and most of his family were massacred in Karbala, in today’s Iraq, in 681 by a political rival, Yazid, based in Damascus.

During a long and arduous journey, the few members of Hussein’s surviving family were taken as prisoners of war across the desert from what is Iraq to Damascus. Khawla died in Baalbek. Zayn al-Abidin, Hussein’s only surviving son, and Khawla’s brother, planted a small branch to mark her grave. Over the years, that branch turned into a massive cypress tree, which is in the middle of the shrine, making it 1,400-years-old.

I sit on a carpet of alternating floral designs of red, black, and white, in front of her tomb. Technically Khawla is like my Khala Maria, my great-aunt, albeit older by more than a millennium and a half.

I pray. For the health of my family, that my sister gives birth to a healthy baby, and that I get some message from Maria in Ukraine that she is safe.

Afterwards, I am on my way to Our Lady of Bechouat, the site of a Marian apparition, because maybe there Ukrainian Maria’s text will also appear.

The church has a bell tower, an exact resemblance to the minaret of the Shi’a shrine, but the entire complex is constructed of monochromatic, soft beige stones, in comparison with the explosion of color in Sayyida Khawla. While the Shi’a shrine has a single tree, this complex is covered in sprawling olive trees.

It was here that in 1741, a wooden Byzantine icon of the Virgin was discovered in a cave and a church was built above it. Bechouat then became a pilgrimage site after a miracle occurred there for a paralyzed Christian man. The Marian apparition, however, occurred later, in front of the eyes of a Muslim child. Since then, I learned it has become a site of pilgrimage for both Christians and Muslims.

It’s fitting it became a site sacred to both Christians and Muslims. In the structure housing the statue, there is a painting of the Virgin Mary, standing on top of a crescent moon.

The crescent moon, along with a star, is a symbol associated with Islam. However, it was originally a Christian symbol representing the Virgin. The crescent moon had long been a symbol of fertility in the Middle East from pagan times, and the star stood in for Mary. It was only in 1453, when the Ottoman Muslims conquered Constantinople, that they appropriated the flag.

Within the span of a few hours in this narrow sliver of land known as the Bekaa Valley, settled by Phoenicians and Romans, known for its hashish, I visited two sites dedicated not just to Christianity and Islam, but the divine feminine: Our Lady of Baalbek, Khawla, and Our Lady of Bechouat, Mary.

The Lebanese often boast about how they can ski in the mountains and be able to go to the beach and dip into the water within the span of an hour. I was more impressed that within the span of an hour I could visit these two shrines, one Shi’a and the other Catholic.

In the span of an hour I could pray for protection, asking one holy Maria to protect both my Syriac Orthodox great-aunt Maria and my Ukrainian Orthodox Maria.

A few days later Ukrainian Maria eventually arrived in Parma, Italy, to stay with her aunt. Her parents remained in Okhtyrka, defending their home.

Maria was safe. And now I had to fulfil a promise before the year ended that I would travel to India, to visit the shrine of my great-uncle, and thank him for the favor.

The views expressed in this opinion article are the author’s and not necessarily those of Kyiv Post.

The original version of this article appeared in The New Arab and can be seen here.

Ibrahim Al-Marashi is an associate professor of history at California State University San Marcos. He is co-author of Iraq’s Armed Forces: An Analytical History and The Modern History of Iraq. Follow him on X: @ialmarashi

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter