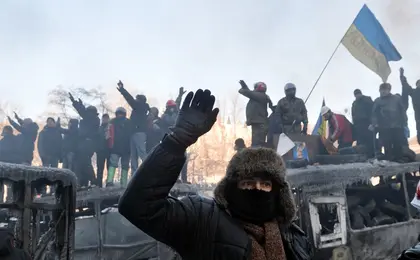

Ten years ago today, young Ukrainians began protests in favor of a European orientation for their country. By a mixture of threats and bribes, Putin had dissuaded Ukraine’s president from signing an agreement with the European Union. After Ukrainian students were beaten by security forces, the protests took on a mass character, now in support of the rule of law. Russian television characterized Ukrainians protestors as fascists and gays, and in late December 2013 Putin began gathering forces for an invasion of Ukraine. In February 2014, right after a massacre of protestors, Russia invaded Ukraine, occupying Crimea and some territory in the eastern region known as Donbas.

This guest text from Marci Shore, focuses on the experiences of the protestors themselves, people who took risks for a better kind of politics, and prevailed. Ukraine did not collapse when invaded in 2014, nor during the full-scale invasion of 2022. Putin (and many others) were mistaken about Ukrainians’ capacity to believe in themselves and in ideals, and to organize themselves to resist. Important as it is to analyze the war as such, there is also the impalpable element of choice, a choice of one kind of life over another. That is the subject here, and it is relevant everywhere. Marci’s book on the Maidan, now updated to bring the account through the war, is Ukrainian Night. This text appeared in German in the taz.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

The ‘Tryzub’ - Ukraine's Proud Trident Symbol

21 November 2014, 10 years later. . .

The present is ungraspable in its dimensionlessness. It has no duration. For Jean-Paul Sartre, the present had to be understood as a border, the border between the realm of facticity—what has already happened and simply is —and the realm of transcendence, an opening to go beyond what has been. Revolution illuminates this border; it is a moment of choice.

In 2004 the team of Ukrainian presidential candidate Viktor Yanukovych, a Kremlin-allied oligarch, committed election fraud—and poisoned Yanukovych’s opponent, Viktor Yushchenko, with dioxin. Mass protests on the Maidan, Kyiv’s central square, forced a second election; this time Yushchenko won decisively. In Kyiv the mood was elated. It seemed Yanukovych could never come back. Yet Yushchenko proved a deep disappointment. And Yanukovych tapped into the American boutique industry of PR for gangster-types with presidential ambitions. Tutored by his Washington consultant, Yanukovych reemerged in 2010 to win the presidential elections, this time legitimately.

Afterwards Yanukovych gave his Washington consultant—whose name was Paul Manafort—a thank-you gift: a jar of black caviar worth over $30,000.

The consolation prize Yanukovych dangled before a liberal intelligentsia that hated him was the distant prospect of European integration. For a young generation in particular, “Europe” was the object of the greatest desire. In November 2013 Ukraine was expected to sign a long-anticipated association agreement with the European Union. At the eleventh hour, on 21 November 2013, Yanukovych refused.

The disappointment was especially crushing for students, who felt as if their future had vanished; Europe would be closed to them. That evening a thirty-two-year-old Ukrainian journalist from Kabul named Mustafa Nayyem wrote in Russian on his Facebook page: “Come on, let’s get serious. Who is ready to go out to the Maidan by midnight tonight? ‘Likes’ don’t count.”

That night Ukrainians—overwhelming students—came to the Maidan—and stayed. They held hands and shouted, “Ukraine is Europe!” At 4 am on 30 November 2013 Yanukovych sent his riot police to the Maidan to beat the students. The violence against peaceful protestors was a shock. Yanukovych, it seems, was counting on the shock to shake parents into pulling their kids off the streets. That was when something remarkable happened: instead of pulling their kids off the streets, the parents joined them there. It was a historic Aufhebung of Oedipal rebellion. Now there were close to a million people on the streets of Kyiv, and they were shouting, “We will not permit you to beat our children!”

One of those beaten children was sixteen-year-old son Roman Ratushnyy.

“Your mother must have been very upset,” I said to him. “But she let you go back?”

“My mother”—he said—“was making Molotov cocktails on Hrushevskogo Street.”

The Maidan became not only a site of protest, but also a parallel polis. Kitchens were operating. Musicians performed, artists painted, physicians treated the injured. There was a library, an Open University, a communal upright piano. People erected tents, built bonfires, and cooked soup in iron cauldrons. Volunteers cleared snow and ice. An LGBT organization transformed its confidential hotline into an emergency hotline for the Maidan.

Borders that normally existed between people dissolved; it became very easy to talk to strangers. “There were very different people,” a student named Misha told me, “Ukrainians, Russians, Jews, Poles, Tatars, Armenians with Azerbajzhanis, Georgians, Ukrainian-speakers, Russian-speakers.” There was a feeling that not only ethnic divisions, but also socio-economic divisions had been overcome. The Maidan was a “laboratory of the social contract,” in one writer’s description, “a union of IT specialists from Dnipropetrovsk and a Hutsul shepherd, an Odessa mathematician and a Kyiv businessman, a translator from Lviv and a Tatar peasant from Crimea.”

The historian Yaroslav Hrytsak described the Maidan as akin to Noah's Ark: it took “two of every kind.” There were people of all political sympathies from radical left to radical right. For the filmmaker Oleksiy Radynski, Europe's discomfort at watching Ukraine resembled Caliban's grimace upon seeing the reflection of his own face in the mirror.

On January 16 Yanukovych’s government passed “dictatorship laws,” revoking the rights of free speech and assembly. Everyone on the Maidan was declared a criminal. Yanukovych’s riot police used tear gas, rubber bullets, stun grenades, and water cannons in sub-freezing temperatures. Protestors were disappearing. An activist’s body was found maimed and frozen in the woods. Those who returned were often disfigured, missing, for instance, part of an ear.

Hannah Arendt described the “character of startling unexpectedness… inherent in all beginnings.” When Ukrainians went to the Maidan on 21 November, no one expected to die there. But by the end of January, after the first protestors had been shot to death by the police, an existential transformation was palpable. The quality of temporality itself changed; people lost track of time, of night and day. In Kyiv no one slept anymore. The Maidan lived in what Walter Benjamin called the Jetztzeit, the-time-is-now-time. A critical mass of people had made a decision: they were willing to die there if need be.

This was the moment—art curator Vasyl Cherepanyn believed—when Ukrainian society as it exists today was born.

* * *

In February 2014 the Maidan culminated in a sniper massacre that left a hundred protestors dead. Yanukovych fled to Russia. The Kremlin illegally annexed Crimea, and sent “Russian tourists” across the border to instigate a war in eastern Ukraine, where a motley crew of Kremlin-backed separatists claimed to be protecting Russian-speakers from the Ukrainian Nazis brought to power by the American-orchestrated fascist coup in the capital. That war has not ended.

During the winter of 2013-2014 Russian journalists continually asked those on the Maidan who had organized them, what help they got from the Americans. “They simply could not grasp,” one young woman described, “that we ourselves organized ourselves.” Kremlin propaganda, the conviction that American intelligence or some other world-controlling force must be pulling the strings, betrayed not only malicious intent, but also an inability to believe that there could be such a thing as individuals thinking and acting for themselves.

Eight years later, in spring 2022, Russian soldiers who occupied Kherson could not believe that the local people who came out to protest were not controlled by “some mastermind out there.” “They weren’t able to consider the possibility,” a woman from Kherson told journalists, “that people who care about freedom, democracy and self-determination are self-organizing.”

Roman Ratushnyy belonged to the generation who had come of age on the Maidan, with its legacy of people who saw themselves as subjects, not objects of history. He became an environmental and anti-corruption activist. When Russia launched a full-scale invasion, he joined the military.

In June 2022 Roman was killed on the frontlines.

Today Ukrainians do not speak about “after the war;” they speak about “after the victory”—пiсля перемоги (pislya peremohy). “Peremoha”— Polish theater director Krzysztof Czyżewski suggested—should become part of a new universal vocabulary. The prefix pere indicates a crossing and moha means “I can.” Peremoha—“victory”—literally expresses a going beyond what one is able to do.

When Ukrainian writer Kateryna Mishchenko’s colleagues talked about the war, they talked about Russian imperialism, about Stalinism and colonization. “For me”—Kateryna wrote—“his war has a fairly clear point of reference – the Maidan. Perhaps it is worth returning to this place to find the future.”

For Sartre, to live in mauvaise foi was to project facticity into the future and so deny the possibility—and responsibility—of going beyond what is. The lesson of the Maidan is that we can go beyond who we have been until now. We can—even if that light illuminating the border that is the present shines only in rare moments, flickers, and then appears to be gone.

Reprinted from Thinking About.

The views expressed are the author’s and not necessarily of Kyiv Post.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter