The Museum of Antiquities on the premises of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra holds a unique collection of precious Scythian artifacts. Another collection, which was previously kept in a museum in Crimea, was brought to the Netherlands for an exhibition in the fall of 2013, several months before Russia annexed the Ukrainian peninsula. The Kremlin then demanded that the exhibits be returned to Crimea, claiming they belonged there, but Kyiv insisted they were the property of the Ukrainian state. The dispute was taken before the Dutch courts and now, after almost a decade of litigation, the case has finally been decided in Ukraine’s favor.

Some seven centuries B.C., tribes of free nomads known as the Scythians appeared in the steppe lands of the present-day southern and southeastern regions of Ukraine. Herodotus wrote that “the Scythians believed Hercules to be their father.” He described Scythian men as “stern, pugnacious, but kind-hearted”. They were robust, pale-faced, blue-eyed and long-haired, wearing mustaches and beards.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Their warlike nature is reflected in their jewelry where the central character is a beast of some sort; an idol to worship and a target to hunt. Early artifacts of Scythian craftsmen obeyed what historians define as “primeval impressionism”. A wild boar symbolized war and victory; a deer symbolized the Sun and fertility; and a horse was a nomad’s friend and helpmate. Even the Scythian king Atheas (ca 429 - 339 BC) would clean and stable his horse himself, to the great surprise of the Greeks.

There is a well-known historical fact about the Scythians. When the invincible army of the Persian king Darius set foot on the Scythian lands, the nomads did not confront the invaders, just wrapped up their tents and disappeared into the wide steppe. Every now and then the Persian army would lose men and horses, as the result of Scythian “hit and run” swoops on their camps, after which the raiders would disappear again – a demonstration of, what we would call nowadays, a guerilla campaign.

The Persian army had never encountered anything like that before. The Scythian king, Idanthyrsus, said to the enraged invaders, “We have nothing to lose. We have no towns, nor fields of grain. Our only possession is the graves of our fathers. Try and loot them, and then you shall see our real force!”

Darius thought it best to retreat and was never again tempted to invade. Several decades later, the Scythian lands were invaded again, this time by the Sarmatians another equestrian-based nomadic peoples from eastern Irani equestrian nomadic, but that is a different story.

One of the artifacts in the Crimean collection – a gold-plated Scythian quiver – depicts events from the life of Achilles, the hero of the Trojan War. The Scythians believed that arrows from that quiver were lethal even to invincible warriors.

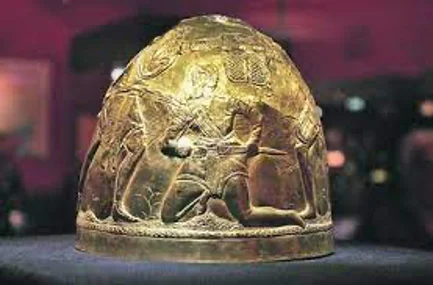

There is also a gold helmet that dates back to the times of Alexander the Great. It recounts a legend of a war between an older generation of Scythians and a younger one, begotten by Scythian women and their slaves. The fierce standoff went on for twenty days and neither side was able to win. Then the older Scythians put their swords aside and took up their whips causing their adversaries to flee; for a slave always remains a slave at heart.

The Scythians are believed to have initiated a ritual known as “fraternization,” which was described in detail by Herodotus: the would-be blood brothers dripped blood from cuts made to their fingers into a bowl, put their sword blades in it, and drank the “fraternal” potion, holding hands. From then on, only death could part them. One of these bowls can be seen in the Kyiv collection.

The Scythians buried their kings dozens of feet deep in large tumuli with side entrances and circular ditches around. They never built churches but fought to the bitter end for the graves of their ancestors.

In bygone times, grave robbers would dig into the center of a burial vault, overlooking side entrances. Borys Mozolevsky, an amazingly gifted Ukrainian poet and amateur archeologist, relied on this fact when mounting an expedition to the barrow called Tovsta Mohyla (Thick Grave) in the south of the Dnipropetrovsk region. There, the burial vault of the Scythian king had been robbed centuries before, but nobody had looked beyond the central chamber.

What he unearthed in June, 1971 at a depth of over 7 meters is what is considered to be one of the greatest archeological finds of the 20th century, on a par with that discovered in the Tomb of Tutankhamen. There, he found the skeleton of a Scythian queen as well as those of numerous slaves and horses that it is believed the Scythians normally buried alive alongside their king. She had been a lavishly clad young woman with gold plates on her garments, a gold head-dress, gold bracelets and rings, and a massive gold pectoral on her chest. Beside her lay the remains of a two-year-old child, also richly clad, who was probably the king’s son.

The most precious find was that gold pectoral, which weighed 1.148 kg, with a purity standard of 900 (over 90% gold content), beautiful ornamented wiyh exquisite high reliefs of animals and people. I saw it with my own eyes and even held it in my hands, and I know the story first-hand, as Mozolevsky told it.

I was just a nine-year-old boy then, but I remember it very well. Mozolevsky was a friend of my parents, and when he brought the invaluable treasures to Kyiv in September 1971, they were exhibited to top government officials in a large room on the premises of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra. The objects were displayed openly, not under glass as you would expect.

Mozolevsky was allowed to bring his wife and closest friends with him. I remember the Scythian king’s gold-plated sword sheath, gold figurines, earrings, bracelets and other adornments, cups and bowls, bronze arrowheads, two brownish skeletons – one large and the other very small, a horse’s skull, and the gnarled bones of a human hand. The fingers left grooves in the clay when the slave was buried alive… That human hand left a very deep impression on the nine-year-old me.

I became dazed and confused when Mozolevsky put the gold pectoral in my hands. It was so heavy and I stood there holding it in my hands, wondering how those ancient people had been able to make such tiny antlers, arrows, and even beards and eyes and individual expressions! I was too small then to realize what a priceless treasure I was holding in my hands. Now I do and I am very proud of that experience.

Later, I read Mozolevsky's beautiful poems inspired by the historic find. And he told us that he had located the Tovsta Mohyla by studying old legends and lore. He called the Gold Pectoral “a comprehensive symphony of the Scythians’ life and worldview” and said that it alone was enough to make his own life worthwhile.

This masterpiece of ancient craftsmanship harmoniously combines symbols of life and death, heaven and earth; a glimpse of everyday life; horses caught in a wild gallop, motion interwoven with emotion; and death treading somewhere nearby. The pectoral's exquisite high reliefs seem to represent the eternal circle of human existence, the frozen harmony of the universe.

It is believed the pectoral contains many secrets which are still unsolved. Scientists and archaeologists and scientists believe it contains a map within its many images which could point to the burial sites of other Scythian kings.

The search will have to wait until the Ukrainian flag flies once more over what were once the primeval steppes which are now trampled by Russian boots …

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter