This month, Europe and the democratic world bid farewell to a great Czech writer, Milan Kundera, who in the view of many, including me, deserved a Nobel Prize for Literature. He died in Paris on July 11 at the age of 94.

Kundera was much more than a brilliant novelist. He was a veritable champion of the East and Central European nations who for so long had to and still have to struggle for survival and freedom against the oppressive forces of despotic Russian imperialism, whether tsarist, communist or post-Soviet. In short, he also assured his reputation as a standard-bearer of liberty, whether on the personal or national levels, or as a defender of memory, culture and identity against their erasure for political purposes.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

As a young student of Ukrainian origin growing up in a free Britain and interested in the fate of the land from which my parents had been torn by the cruelties of history, I discovered Kundera sooner than most. I enjoyed reading his entertaining and provocative novels very much, set in his native Czechoslovakia, replete as they are with insights into the human condition – the unbearable lightness of being, as he termed it in the title of one of his most famous works.

But the political dimensions of Kundera’s writings also captivated me.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s I had the privilege of heading the unit in Amnesty International’s London headquarters defending Soviet prisoners of conscience. Inevitably, I came into contact with, and made common cause, with Czechoslovak and Polish dissidents and their supporters. From among those connected with Czechoslovakia, I’ll just mention the phenomenal playwright Tom Stoppard, and George Theiner, the kindly, receptive deputy editor of the then still new monthly pioneering magazine defending writers and freedom of speech, Index on Censorship, where some of my first journalistic articles appeared.

Six Ways Ukraine is Winning: The Rise and Rise of Ukrainian Culture

Within his frequently witty and humorous prose, Kundera conveyed important messages about the nature and impact of Russian-imposed communist rule, why the Prague Spring of 1968 had sought to free Czechoslovakia from its stranglehold only to be brutally suppressed by tanks and dictatorship, and why it was important to remember the plight and resistance of Europe’s other half and what it represented.

“The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history. Then have somebody write new books, manufacture a new culture, invent a new history. Before long that nation will begin to forget what it is and what it was... The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting,” Kundera emphasized in his novel The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, first written in Czech.

At that time, apart from Albert Camus, no modern writer had such an impact on me. And when I realized that he was speaking out not only on behalf of this own country but that of neighboring ones, including Ukraine, I became an even greater fan.

In those days, the problem of forgetting about, writing off, or simply ignoring nations languishing under Soviet rule, was a very real one for those of us trying to draw attention to the resilience, heroism and aspirations of the Central and East Europeans in the broadest sense.

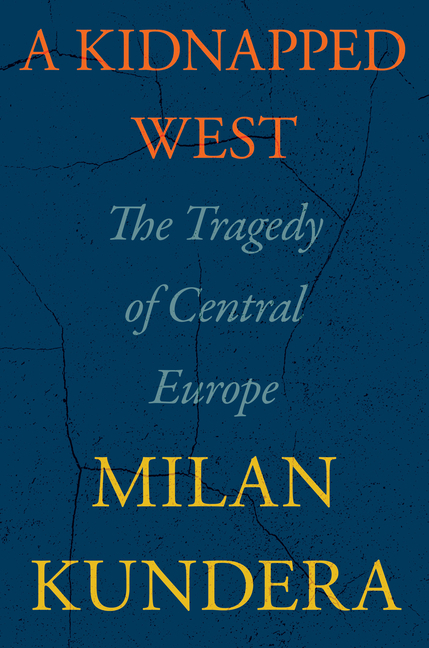

In 1983, while in exile in Paris, Kundera wrote an essay entitled “A Kidnapped West” in which he pointed out: “Today, all of Central Europe has been subjugated by Russia, with the exception of little Austria.” According to Tibor Fischer, writing in The Spectator in May 2023, “his essay can be summed up as: we’re so cultured, we’re so westernized, why don’t you care we’ve been kidnapped by Russians who’ve never seen a flush toilet? Unfortunately, there wasn’t much concern about the ‘other Europe,’ the vassal states of the Warsaw Pact, in the cultural spheres.”

The situation was even worse in the case of the non-Russian nations under Moscow’s rule – Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, Belarusians, Georgians, Crimean Tatars, and others. I was among those who tried their best to remedy things and in 1990 wrote Soviet Disunion – A History of the Nationalities Problem in the USSR, which subsequently appeared in British, US, French, Italian and Japanese editions.

But the going remained tough: while sympathy for East and Central European dissidents had grown in the 1980s because of the appearance of the Charter 77 and Solidarity movements in Czechoslovakia and Poland, empathy for non-Russian activists espousing freedom within the USSR was seldom forthcoming. More often than not, parroting the official Soviet line, they were dismissed as problematic “nationalists.”

I’ll provide a poignant example of this blinkered mindset even among liberals and “lefties” championing freedom in other countries. In early 1981, one of the leading British novelists, Graham Greene wrote a letter to the editor of The Spectator in which he expressed his disagreement with my exposure of the forced Russification of the non-Russians within the Soviet Union and the opposition it was generating. “Surely any Empire has to impose a lingua franca,” he retorted.

A few years later, as I was completing another book, The Ukrainian Resurgence (1999), I was still seeking to draw attention in the introduction to the “erroneous but widespread tendency to regard Russia and the Soviet Union as one and the same thing and the failure to understand the actual nature of the multinational former Soviet empire.”

I cited the British historian Norman Davies who in his major history of Europe wrote: “The best thing to do with such an embarrassing nation,” which refused to disappear meekly under both tsarist and Soviet domination, “was to pretend that it didn’t exist.”

But here Kundera also provided me with a very apt, if depressing, observation made in his early version of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting: “Over the past five decades, forty million Ukrainians have been quietly vanishing from the world without the world paying heed.” It made the point.

And the relevance of Kundera for today? Especially in view of Russia’s war on Ukraine. Here are a few recent responses.

In an article entitled “Milan Kundera and Ukraine’s place in Europe,” published in the July 2023 issue of Prospect, Princeton professor Rhodri Lewis states: “The writer’s works have been recontextualized by the ongoing invasion, now that the freedoms he espoused are once again under immediate threat.”

Lewis notes that “neither history nor literary history run along straight lines, and Kundera’s currency has seldom felt stronger than it does today. This is the doing of an unlikely and unwitting benefactor: the Russia of Vladimir Putin. The invasions of Ukraine in 2014 and 2022 have been a vivid reminder of that which, for Kundera, was always at stake: the freedom of individuals, particularly those in the nations that were constrained to exist within the eastern bloc, to express and enjoy and endure the perplexities of the human condition.”

Le Monde on July 22 in its introduction to an op-ed entitled “Milan Kundera outlined a certain idea of Europe,” wrote: “Political Scientist Jacques Rupnik looks back at the intellectual legacy of the Czech-born writer, whose reflections on Central Europe, which he described as a ‘kidnapped West,’ take on particular resonance today in the context of Russia's war against Ukraine.”

And in the above-mentioned article, Fischer comments: "Something that wouldn’t have surprised Kundera is Russia’s barbarous war in Ukraine. Merely Russian business as usual: kill, deport, lie, repeat – though not necessarily in that order… From the go, my Russian friends – mostly writers – viewed Putin as a KGB thug and were puzzled by the generosity of the West towards him. But what bewildered and infuriated them most was that the majority of their fellow citizens were unconcerned about Putin, or actually liked him.”

Today, Kundera’s works have a new resonance. That is why we need others to follow in his footsteps to ensure that we do not forget and that we don’t allow, as he put it, “those who want to be masters of the future only for the power to change the past” to have their way.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter