June 6 is the Day of the Journalist in Ukraine. It has me thinking about my own career in the profession, spanning more than 40 years, about some of the highlights, and some of the lessons learned.

The son of Ukrainian wartime refugees born in Britain, in the provincial industrial town of Wolverhampton, as a young boy interested in Ukraine I could not imagine being published in the best of Britain’s press.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

But the late 1970s were a propitious time. Despite having a name and surname that did not sound British at all, thanks to the country’s system of fair play and meritocracy, which had already surpassed the traditional class and old boy systems, I was eventually able to make it to the Olympus of British journalism.

How, you may ask. Well, for a start, having a father, who knowing my interest in history and politics, and sensing I had some talent, kept convincing me that I should go into journalism and study politics.

Good teachers in a Catholic grammar school (St. Chad’s College) instilled in me a love of literature and the English language, complete with training in the art of public speaking and debate.

At the University of Leeds, I was advised by a brilliant young professor of history, David Dilks, to learn how to “imply knowledge” and avoid turning on a hosepipe spewing out information ineffectively.

A year in Canada, in 1974-75, as a Masters Student in Modern European History in Winnipeg, at the University of Manitoba, helped me to realize that cultural differences exist even between people speaking the same language – in this case, English – and that you cannot always assume you are on the same wavelength.

Also, that the sense of identification with Ukraine demanded a far broader and honest appreciation of what it entails than I had hitherto encountered growing up within the somewhat blinkered Ukrainian community in Britain.

The example of the vibrant longstanding Ukrainian diaspora in Canada, and what I learned from such enlightened professors of Ukrainian origin teaching there at that time, such as Yaroslav Rozumny and Ivan Lysak-Rudnytsky, about what was happening in Soviet Ukraine, helped me to mature as a “concerned” British-Ukrainian.

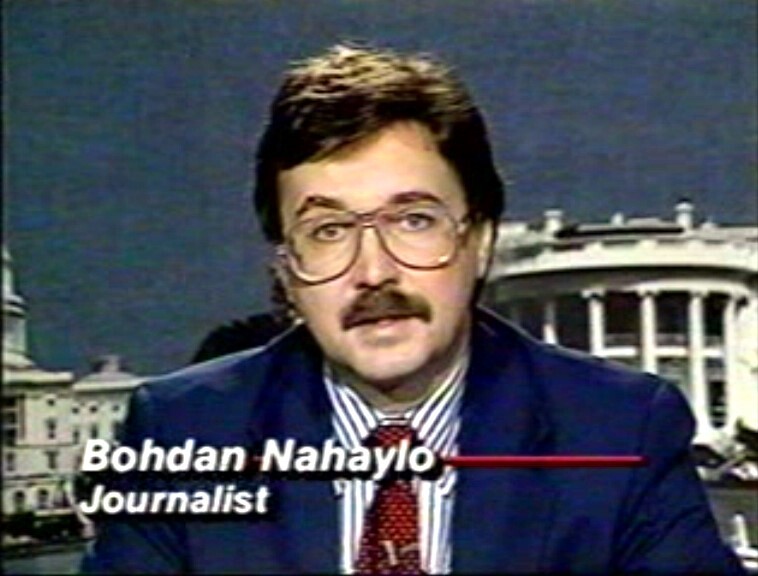

Bohdan Nahaylo predicting the dissolution of the Soviet Union, live on CNN in July 1990.

From 1975, I was enrolled as a Ph.D. student at the London School of Economics and Political Science. My topic was very exotic for Britain in those days – Ukrainian national assertiveness in the 1960s under the local Communist Party leader at that time – Petro Shelest.

I’m grateful to my professors and tutors there – Peter Reddaway and Leonard Schapiro – for accepting a post-graduate student on a non-Russian “Soviet” theme and grasping its significance.

Reddaway was a leading supporter of Soviet dissidents and an opponent of political abuses of psychiatry. He got me translating into English the main underground Russian human rights journal: A Chronicle of Current Events.

In 1978, with my tutor’s recommendation, I got a huge break. Amnesty International hired me as its official responsible for researching, publicizing, and organizing its work in defense of all Soviet prisoners of conscience.

Soon, I was also publishing articles in the London-based Index on Censorship about imprisoned Ukrainian writers.

1980 was the crucial year. Let me remind readers: the leading Russian dissident Andrei Sakharov was isolated in internal exile within Russia, and the Olympic Games taking place in Moscow were boycotted by the West. Soviet troops were in Afghanistan.

A time of tension, it brought renewed interest in what the Soviet Union was about. What would happen when the ailing Kremlin leader Leonid Brezhnev left the scene? What should the West’s relation be with this still strong, but already evidently declining nuclear superpower? Should the West assist Moscow in building an energy pipeline from Siberia to Europe? How far should it go in agreeing to arms reductions, or for that matter in supporting dissidents in the communist bloc?

I was disappointed with the level of writing about the Soviet Union. Eventually, I decided to try to inform the discussion about the Soviet Union. My aim was to raise awareness about realies, and not just the obvious elements of its enduring power and the threat it posed, but also its weaknesses, in particular the nationalities question which few in the West at that time wanted to acknowledge as a serious factor.

I made my first try in early 1980. My very first article dealt with a rather obscure subject – the potential for the resurgence of Islam in Soviet Central Asia.

Not expecting success, I offered my piece simultaneously both to the New Statesman and to The Spectator. Christopher Hitchens was the foreign editor of the New Statesman and immediately agreed to publish it. I got an irate phone call from the editor of The Spectator, Alexander Chancellor, who called me in to give me a dressing down.

He told me that I should have had the courtesy to submit the article to one publication at a time. Chancellor turned out to be an amazing editor. He was interested in foreign affairs – not simply a “Champagne Charly,” as some of the more traditional associates of The Spectator were called. He told me that if I stuck with The Spectator, if my articles proved to be of the quality they were looking for, I could become their regular columnist on “Soviet” affairs.

Over the next few years, I was given effectively free rein by Chancellor to write for his respected weekly. I published around 90 pieces for that publication on all sorts of issues, from political and economic, to the challenges of nuclear disarmament. This was when the likes of Tim Garton Ash were also gracing the pages of this renowned publication.

I’m proud that in 1983 I was also able to get a piece published dealing with the Holodomor, that I was able to cover other topics of interest to non-Russians and Russians struggling for their freedom, including a description of the plight of the Crimean Tatar nation.

One of the highlights was when in early 1981 Graham Greene wrote a letter to the editor of The Spectator in which he expressed his disagreement with my exposing enforced Russification within the Soviet Union and the opposition it was generating in the Russian republics. “Surely any Empire has to impose a lingua franca,” he retorted.

Subsequently, I was also often published in The Times, Observer, occasionally the Guardian, and then very frequently in the Wall Street Journal, European edition.

Questions were now being asked about what was happening in Moscow after the death of Leonid Brezhnev, about his short-term successors Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, and later about the arrival in power of a much younger party leader, Mikhail Gorbachev. And then of course the Chornobyl nuclear disaster in 1986, perestroika, glasnost, etc.

There was a thirst for information and commentary about the Soviet Union. I was fortunate to be in the right place at that time – London, and later Munich, and to have access to sources that were not available to most. Remember, there was no internet in those days.

In 1994 I was invited by the American directorship of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, broadcasting from Munich to the former Soviet Union, to work for them. I spent 10 years there mostly as a senior research analyst, writing hundreds of analytical pieces in English that were published and available to all interested subscribers.

But for two and a half years, from 1989 to 1991, I headed the Ukrainian service of Radio Liberty and was directly involved in radio journalism.

In June 1990 I was the first correspondent from Radio Liberty to be allowed into the former Soviet Union and visited Ukraine for the first time. The following month I predicted live on CNN that the collapse of the Soviet Union was now inevitable because democratization and the preservation of empire were incompatible. And, because by then Ukraine had begun freeing itself from the deadweight of the oppressive Soviet Russian imperial system and finally stirred.

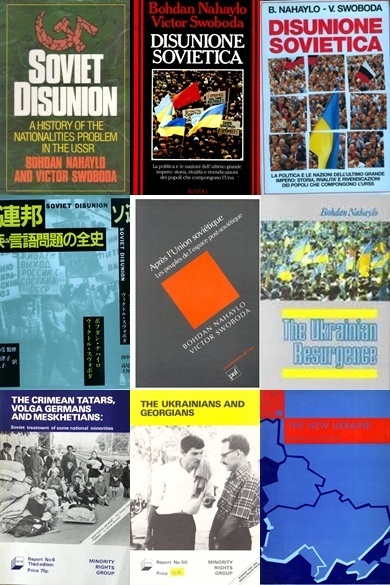

A selection of Bohdan Nahaylo's publications

In October 1990 I took the first unvetted interview with a Soviet Ukrainian leader. Sitting in his office, under a portrait of Lenin, the then speaker of the Soviet Ukrainian parliament Leonid Kravchuk, who subsequently became the first president of independent Ukraine, nervously answered my probing questions.

In these exciting and challenging times, I established a network of reporters within Ukraine itself. In Kyiv, it was headed by the late great journalist and former political prisoner Serhii Naboka.

On Aug. 24, 1991, thanks to my new colleagues in Kyiv, Radio Liberty was the first to broadcast the news that Ukraine had just declared its independence.

After this immense milestone, it was time to move on and accept other challenges. My acclaimed book Soviet Disunion appeared in five editions – British, US, French, Italian and Japanese, and it eventually landed me a job with the United Nations, as the Senior Policy Advisor on the former Soviet region for the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

From 1994 to 2015 I worked in various senior positions for the United Nations – including as UNHCR’s Representative in Belarus, Azerbaijan and Angola, and finally as the Chief of the UN’s Department of Political Affairs (DPA) team in Kyiv. Understandably, during this time, I could not publish as a journalist.

After retiring from the UN, I gradually returned to journalism and providing political commentary and analysis. I contributed to, among others, Atlantic Council’s UkraineAlert, Kyiv Post, Ukrainian Weekly; was a columnist for Ukrainian International Airlines magazine Panorama; and host of radio programs in Kyiv.

Having contributed to the birth of independent media in Ukraine more than 30 years earlier, I cannot say I was pleased with what I saw.

For certain, there was a pluralism of views, but oligarchic controls, low standards and widespread lack of integrity raised serious questions about the quality of the journalism being offered.

There was much that needed improving. Staged political talk shows as well as the proliferation of “expert” bloggers, know-all oracles and Cassandras became part of the problem, not the solution.

So was primitive hate-mongering, mud-slinging and dissemination of confusion through disinformation and manipulation of facts by paid agents of influence masquerading as journalists, not to mention bots.

The political atmosphere began to change for the better after 2019, as the influence of the oligarchs and of pro-Russian forces began to be curtailed.

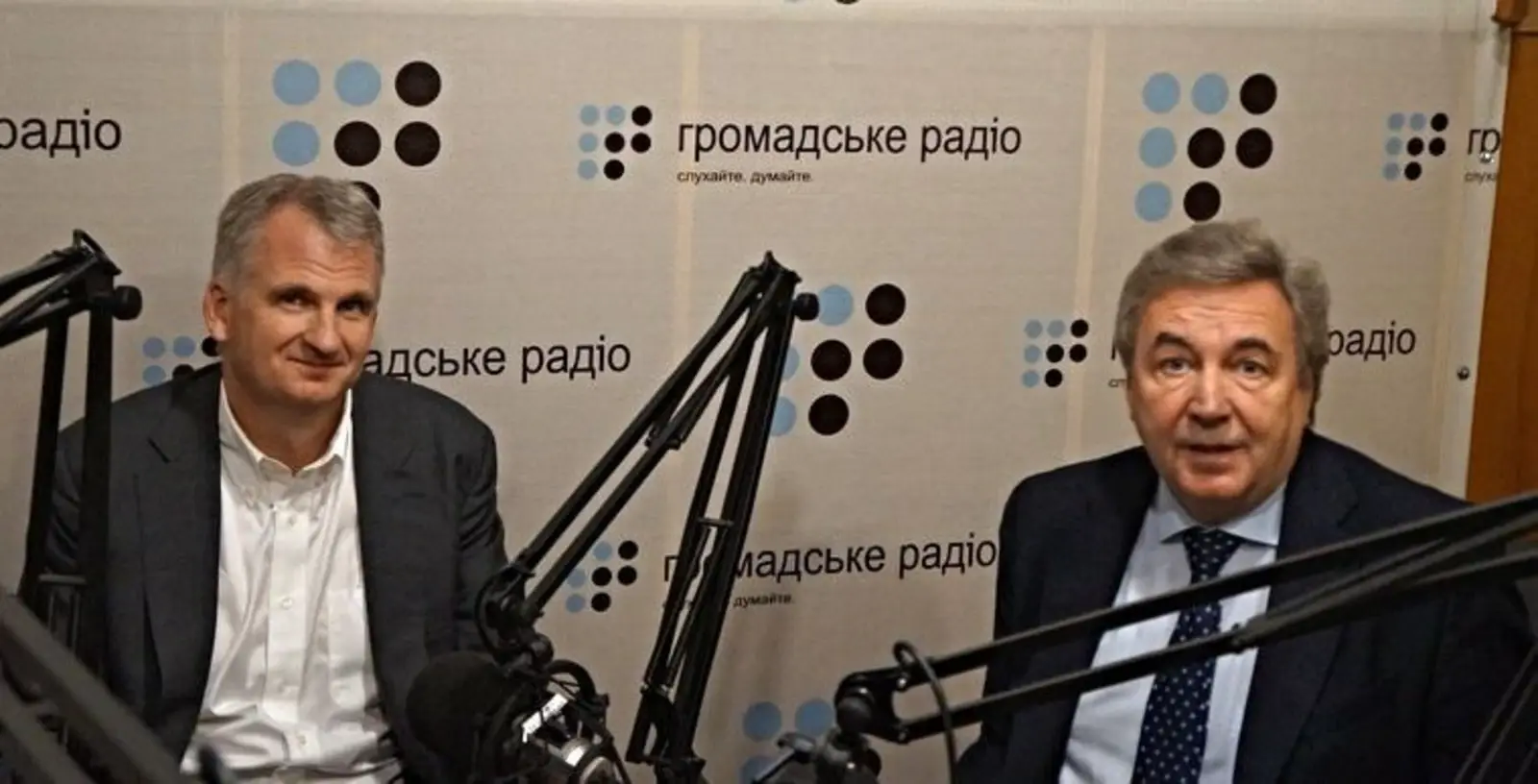

Interviewing Timothy Snyder for Hromadske Radio in Kyiv in 2016

I was fortunate again to be given the immense responsibility at the end of 2021 to become the Chief Editor of the revamped Kyiv Post, Ukraine’s oldest English-language news publication and its “global voice.”

But even this proved to be a considerable challenge. Kyiv Post, under its former long-standing editor Brian Bonner, was briefly closed down in November 2021 by its owner Adnan Kivan after a mutiny on board by a complacent core who felt threatened by the owner's desire to launch a Ukrainian edition, and expand into video and podcasting. I was Bonner's deputy at the time and witnessed what occurred at first hand.

Aftra several weeks, Kivan called the rebels' bluff and responded firmly to Bonner's indecision. They stormed off claiming gratuitously that they were defending press freedom and editorial independence. They abandoned Bonner himself but managed successfully to raise significant funds on the basis of their distorted vesion of what had occured to launch their new publication.

In the meantime, I was invited to an empty office and newsroom to rebuild and revamp Kyiv Post - quite a tall order.

The start of Russia’s all out-war against Ukraine in February 2022 made this daunting task all the more challenging, but vital. Fortunately, with the strong support of our owner. Kivan, and CEO, Luc Chénier, a new team was gradually assembled that has weathered the storms and risen to the occasion.

Today Kyiv Post has on average between 3 to 4 million readers a month, mainly in North America, the UK and western Europe, a reputation for reliability and excellence, internally acclaimed contributors, a new Ukrainian edition, an active and diverse presence on social media, and has expanding into video and television. And most of the team are young, both Ukrainians and non-Ukrainians.

I’m fortunate that just as when I was able through Radio Liberty to have an initial impact on the journalistic “start-ups” of the day, today, through the Kyiv Post, we are able to serve as a benchmark for other journalists and media, and as a proven trustworthy source about Ukraine and its geopolitical context during a time of war, fake news and cheap populism.

Thanks to all my mentors, editors, colleagues, critics and loved ones who have helped me reach this stage in my long and rich career as a journalist in the service of truth, decency, humanity, Ukraine, and democracy.

This is a revised updated version of an article that first appeared in Kyiv Post exactly a year ago.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter