There’s a lot of talk about Satan these days. Much of it can be heard on Russian TV.

Having dispensed with their campaign against “Nazis” in Ukraine (obviously they had trouble seeing beyond their own Wagnerian SS and Kadyrovite stormtroopers), Russian propagandists are now calling for the annihilation of no less than Satan himself. Even Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church and Russian President Vladimir Putin have invoked the notion of the fallen angel now running rampant in Ukraine.

The reality of course in Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine, is that whatever metaphor or anthropomorphism you use (or choose to reject), the presence of evil has become painfully visible to anyone prepared to open their eyes. It’s taken on the names of real places: Bucha, Mariupol, Izyum – places where unspeakable terror has been carried out on people who quite simply have been resisting genocide.

Most of the world has been watching – in horror. And most of the world knows exactly what it is. Evil.

A brief foray into theology

The problem of evil: How can God – who is supposed to be all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good – still allow evil to exist? Either God is lacking in one of those three attributes – omnipotence, omniscience, absolute goodness – or what we deem to be God is actually complicit in evil.

I admit, I’ve never resolved this problem and don’t intend to try here. Various traditions have elaborated some version of theodicy (the theological term for justifying God amid the existence of evil). Mainstream Christian theology conceives of evil as a sort of privation of good. Indian philosophies understand it similarly, in terms of ignorance. Some theological traditions perform an array of intellectual summersaults and backflips to justify the “necessity” of evil by insisting that human beings have free will – and that they must be free to commit evil if God is to be revealed fully.

I can follow the arguments – at least most of them. But frankly, in trying to play the conceptual game of fitting the pain and death of innocents into some theological schema, I find myself estranged from the day-to-day reality of human beings. Moreover, I feel as if doing so in the face of so much suffering is rather obscene.

If I’m to explore why human beings willingly inflict pain on one another and indulge in cruelty, then I prefer to look at flesh and blood lives rather than concepts. In this light, I prefer literature to philosophy.

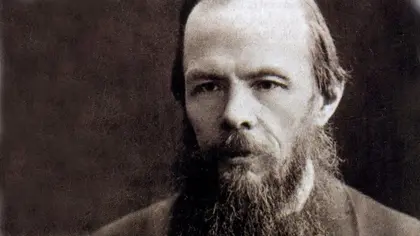

Dostoevsky’s rebellion

Perhaps no other literary figure in the world has devoted so much of his oeuvre to the problem of evil as Fyodor Dostoevsky has. The 19th-century Russian novelist’s magnum opus “The Brothers Karamazov” is a bottomless plunge into the problem of evil from countless angles.

One chapter in particular stands out: “Rebellion.” It consists of a long conversation between two brothers: Ivan and Alyosha. Ivan considers himself a free thinker; whereas Alyosha, an aspiring monk, is deeply influence by his “starets” (spiritual elder), Zosima, who preaches universal love.

Ivan simply cannot resolve the problem of evil. He struggles to explain the suffering of innocent children. He goes on for pages, reciting a vicious litany of episodes he’s either heard of or read about or witnessed firsthand – episodes of abject cruelty, especially to children. At one point in the novel, in a feverish state, he even encounters the devil himself.

It’s not that Ivan denies the existence of God. That would be too easy. He refuses to take a position on whether God created man or vice versa. He even grants that some sort of eternal harmony might come at the price of innocent people suffering unjustly. But he wants no part of any God who would allow innocent children to be tortured. “If all must suffer to pay for the eternal harmony, what have children to do with it, tell me, please?” Ivan asks. “It’s beyond all comprehension why they should suffer, and why they should pay for the harmony.”

Ultimately, he concludes to his devout brother: “Too high a price is asked for harmony; it’s beyond our means to pay so much for it. And so I hasten to give back my entrance ticket, and if I am an honest man I am bound to give it back as soon as possible. And that’s what I’m doing. It’s not God that I don’t accept, Alyosha, only I most respectfully return Him the ticket.”

All you need is love

Although Dostoevsky is also considered a “religious thinker,” his philosophy comes through the characters he portrays, rather than any formal logical argument.

If Dostoevsky proffers anything that might resemble an antidote to the problem of evil, then it’s the figure of Father Zosima, Alyosha’s spiritual elder, who was modeled on a conflation of actual Christian mystics. “Love all of God’s creation, both the whole of it and every grain of sand. Love every leaf, every ray of God’s light. Love animals, love plants, love each thing. If you love each thing, you will perceive the mystery of God in things. Once you have perceived it, you will begin tirelessly to perceive more and more of it every day. And you will come at last to love the whole world with an entire universal love.”

Naturally, Ivan cannot reconcile the problem of evil. As Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart writes in “The Doors of the Sea,” his short, incisive examination of the problem of evil (no, Hart does not reconcile the problem either): Zosima “constitutes a kind of ‘answer’ to Ivan, though not certainly a direct answer. Rather, in his person and in his teachings, he represents so radically different a perspective upon the whole of created reality that it is almost as if he and Ivan inhabit altogether different worlds (and, in a sense, they do).”

Not only is Ivan unable to reconcile the problem, he goes stark raving mad. But not before he manages to sow the seeds of doubt in his pious brother, Alyosha, who begins to catch whiffs of Satan’s sulfur despite his prayers.

Evil over Ukraine: the Yellow Prince

Throughout his works, Dostoevsky describes what his character Ivan calls a “peculiarly Russian” expression of cruelty and evil. Over the centuries this manifestation has settled all too often over Ukrainian soil.

But Dostoevsky, who died in 1881, didn’t get to see the 20th century – in which one span of 30 years, roughly between 1915 and 1945, saw forces of evil lay waste to Ukraine and its population from every conceivable direction.

Twentieth-century Ukraine produced one writer who was forced to address the problem of evil on his own skin: Vasyl Barka (1908-2003). Born near Poltava, he rode the wave of Ukraine’s cultural revival in the 1920s. His poetry was suppressed by the Bolshevik regime for its spiritual tendencies. In the winter of 1932-33 he survived the Holodomor. When World War II broke out, he joined the Red Army. He was wounded and taken prisoner to Germany, where he remained until the war ended. Eventually he made his way to the U.S., where he lived in exile for half a century.

Barka was a prolific poet, novelist and religious thinker, but he is best known for his novel “The Yellow Prince,” a grim account of one Ukrainian peasant family and village during the winter of 1932-33. His works were banned in Soviet Ukraine until the Glasnost period. In 1991 a film, “Famine ’33,” was made based on “The Yellow Prince” and shown throughout Ukraine on the eve of the vote for independence.

In short, “The Yellow Prince” is the account of a simple peasant family, especially the three children, and their rapid descent into hell amid hunger and Bolshevik terror. A genocide novel, it is a nightmarish cross between Primo Levi’s “If This Is a Man” and John Bunyan’s “The Pilgrim’s Progress.” What happens to the fictional Katrannyk family – episodes based on real events that Barka witnessed firsthand – makes Ivan Karamazov’s litany of human cruelty seem like frat-boy hazing in comparison. In “The Yellow Prince” we get an account what happens when the forces of evil seep into an entire society – from ideology to government to simple peasants and the earth itself.

I had the privilege and honor of meeting with Barka often in the last 15 years of his life, and working with him on translations of his poetry. He even became a “starets” of sorts for me.

Barka occasionally talked about the presence of evil he experienced during those months of hunger, which he tried to depict in his book. “Everything around me began to turn yellow,” is how he described it. Hence, the yellow prince.

Black earth redemption

There is no “happy ending” in “The Yellow Prince” (though one might say we are working on it right now with this war for independence). Yet Barka was a Christian mystic. He saw hope and universal love everywhere – even when staring at the Yellow Prince himself.

Moreover, Barka’s vision of universal love was intimately related to the mystery of the earth: how it regenerates and nurtures all life on this planet. If his vision frequently soared through ethereal realms, the source of that vision was always the earth from which flesh and blood is fed and eventually comes to rest.

It’s as if Barka’s answer to the evil “spreading like a miasma from the north” were secreted away somewhere in the ground now being fought over – not some abstract principle, but a mysterious force suffusing the very soul of the earth.

As the novel concludes, the lone survivor, a young boy walking down a road into dire uncertainty, sees a cloud-like form on the horizon:

“The flickering pillar scatters lightning from every direction, like storm clouds, into the vault of the sky, takes the shape of the chalice that the peasants hid in the black earth, never betraying its secrets to anybody as they died horrifically, one by one in a vicious circle.

“It seems to descend on them, with incorruptible and invincible power: eternally offering salvation.”

Vasyl Barka in 1991. (Photo by Caterina Zaccaroni)

The views expressed are the author’s and not necessarily of Kyiv Post.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter