Yulia Marushevska is one of Ukraine’s rising stars, but sometimes it seems that she is fighting corruption in Odesa’s lucrative ports all alone. She says bosses in Kyiv are her biggest obstacles to progress.

ODESA, Ukraine – When Yulia Marushevska was appointed head of the notoriously corrupt Odesa customs a year ago, there were high hopes in Ukraine and abroad that she’d soon clamp down on shady schemes at the country’s biggest ports.

Marushevska, a former member of the team of Odesa Governor Mikheil Saakashvili, rose to prominence as an activist in the EuroMaidan Revolution. Her face was familiar as the star of the “I am a Ukraine” video, viewed 8.7 million times. She also had a squeaky-clean reputation which, a year later, remains intact.

But hopes that she’d produce rapid results are fading.

That’s not to say she hasn’t made some progress: 37 countries with advanced customs procedures (mostly ones from the European Union) have been included on a “Golden List” for expedited customs processing.

Companies importing to Ukraine from one of the Golden List countries can spend as few as 15 minutes, and no more than one hour, undergoing customs registration of their goods. Before, they’d spend up to five hours.

A new modern customs terminal, which will house one of eight departments at Odesa Port and that will be staffed entirely by new, better-paid staff, is nearing completion. And many of the criminal schemes involving private warehouses and logistics terminals surrounding the Odesa port have been sharply curtailed through carrying out full customs registration on the spot, inside the port.

However, it’s far from certain if the changes that Marushevska has pushed through, and her pilot project, which will debut in the new terminal, will survive over the long term. If anything, her team’s presence and attempts to shake up customs controls have highlighted the enduring strength and extent of corruption in the Ukrainian state.

The schemes that prey off businesses who lack connections or refuse to pay bribes, as well as dozens of bureaucratic attacks against Marushevska, lead back to the highest levels in Kyiv.

Roman Nasirov, Marushevska’s boss and head of the State Fiscal Service, has been her main bane, although many more high-ranking officials from a range of bodies have been involved in attempts to block her reforms, she says.

Nasirov has tentatively agreed to an interview with the Kyiv Post, but it was not yet scheduled by the time this Legal Quarterly went to print.

The sheer number of interests working against her means she will probably have an even tougher year ahead, especially if the media spotlight on her work dims.

Pilot Project

It’s been one year since the pilot project began – and five months since it was due to launch.

Known as the Open Customs Space, its goal is to entirely transform one department out of eight at Odesa Port, the biggest of the five ports in Odesa Oblast.

A new, almost completed, modern terminal building will house 130 new staff who have undergone special training programs, including with U.S. customs specialists. They will use the “one window” principle, by which if a company has all the necessary and correct documentation, it should have its clearance carried out by a single customs official in one place.

If the Cabinet of Ministers signs the decree required to open the new terminal, the new customs officials will be paid Hr 10,000 a month – about $400, or around four times the amount a current customs inspector earns.

The decree will also approve the introduction of a new information technology system in the terminal, and automatically approve its use elsewhere in Ukraine.

The system’s software, named ASYCUDA, was provided free to Ukraine by the United Nations, and is currently used by 80 countries. It offers more accountability and transparency than the current program, Inspector 2006, where data can be retrospectively changed from Kyiv.

The cost of introducing the software and training officers to use it is estimated to be about Hr 17 million ($700,000) – a small amount, according to Marushevska, given that Odesa’s customs sends around $2 million to the state budget in customs revenues per day.

But getting the final go-ahead for the pilot project could be difficult.

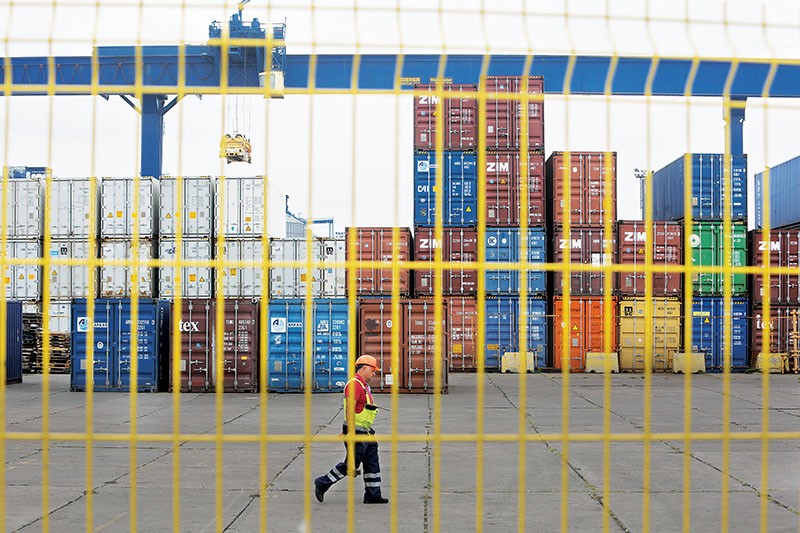

A worker walks past containers in the Odesa port on Aug. 29. New leadership at the port is struggling to cleanse it of corruption. (Volodymyr Petrov)

Hostility from Nasirov

Nasirov, despite initially vowing to support Marushevska’s initiatives, has since been hostile to all of the proposed changes at Odesa Port, according to Semon Kryvonos, the deputy head of Odesa customs.

Nasirov’s disruption of their work has included a slew of office searches by officials from Kyiv due to alleged legal violations, Kryvonos told the Kyiv Post, saying these were attempts to have members of the new team dismissed. He described how one week, seven separate groups of investigators from the State Fiscal Service turned up to search Odesa customs’ offices.

“There wasn’t enough space to seat them all,” said Kryvonos. “They even duplicated what they were doing. In the end, two groups filed exactly the same complaint, word for word, copy and paste.”

Nasirov has so far reprimanted Marushevska four times. Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman dismissed three during his visit to the port in May. Three reprimands are usually enough for officials to lose their job. Asked why Nasirov hadn’t fired her, Marushevska told the Kyiv Post that he is afraid to do so, because she was appointed by Saakashvili and President Petro Poroshenko.

The latest clash between the officials in Odesa and Kyiv has led Marushevska to take Nasirov to court: Nasirov refused to approve Marushevska’s candidate to head the pilot project, Roman Bakhovskyy, who previously headed police reform in Lviv.

Instead, Nasirov has attempted to appoint his own people through non-transparent competitions, according to Marushevska.

Bakhovskyy is, meanwhile, working as the deputy head of the project, the highest position to which Marushevska can appoint him without Kyiv’s approval. Marushevska is also claiming in court that Nasirov is blocking disciplinary proceedings against customs officials suspected of corruption. The court hearing is set for Sept. 28.

The main problem is, according to Bakhovskyy, that everything is still centralized and must be approved by Kyiv. “If you’re in the middle of the vertical of power, which is where we are, it’s really hard to make moves,” added Marushevska.

The nut mafia

Ukraine is the fifth biggest walnut producer in the world. Exports, however, are monopolized by a small group of companies rumored to have links to officials in Kyiv. Walnut producers told investigative website Censor.net in July that they pay between $9,000 to $12,000 per container to have these companies export their nuts. The export monopolizers pay very little in customs duties, producers claim.

Producers who try to export nuts by themselves face huge problems. At the border they are either forced to pay thousands of dollars in bribes or have their shipments confiscated by the Ukrainian Security Services for “contamination inspections.” The process of getting confiscated nuts back is near impossible without the right connections.

Saakashvili has staged two high-profile raids of depots holding confiscated nuts in Odesa Oblast in the last six months.

In both cases, the nuts were confiscated in Odesa on the orders of a Kyiv prosecutor by the SBU, Ukraine’s security service. The deputy head of the SBU, Pavlo Demchyna, has been accused by Saakashvili of running the nut exporting scheme.

In the latest case in April, as a container was surrounded by heavily armed and masked special services men, Saakashvili told the men in front of a crowd of journalists that this was outright robbery, and successfully returned the shipments to the owners.

Groysman announced in May that he would rid the country of the nut mafia and their “tax squirreling” ways.

During his May visit, Groysman behaved like a man who could make anything happen, and showed off by embarrassing Nasirov in front of a crowd of journalists. Groysman has since made several big shows about getting rid of corruption in customs, but they’ve yet to amount anything concrete.

The decree on opening the new terminal has still not been signed, the nut mafia is still operating and Marushevska’s conflict with Nasirov has only gotten worse.

Change for some, not for others

Shailendra Bakshi, an Indian tea importer who has lived in Ukraine for 30 years and has been using the port since 1990, agrees that the customs clearance is now quicker – even though his company is not on the Golden List. Overall though, he doesn’t believe much has changed. His main gripe is the calculation of customs duties, which he said is done very subjectively.

The current system effectively means that different customs offices can charge different prices, leading to “agreements” being reached between businesses and officials. So it can be beneficial to declare goods in Kyiv or elsewhere, while actually transiting them through Odesa.

Marushevska has introduced customs duties by contract for large tax payers, and this has been received positively by those affected. She reported on Sept. 1 that there was an increase in revenues of Hr 242 million ($9.68 million) in August 2016 (to a total $50 million) compared to August 2015, and that 650 new companies had started to use

Odesa customs since the beginning of the year.

She also introduced a helpline for those doing business at the port, which they can also use to report corruption. But Bakshi says that reporting corruption only leads to being blacklisted by local customs officials, so most won’t bother. He also said that many larger businesses are able to negotiate their customs duties at the top levels, which means they are able to out-compete smaller importers.

Meanwhile, the low wages paid to customs officials are still engendering corruption.

“Yes there are fewer checks,” said Vadym Sedov, a senior customs official who led the Kyiv Post on a tour of Odesa port. “But you can’t talk about (tackling) corruption. Would you work for $100 a month? Until you sort out the salaries you won’t solve a thing.”

The 200 customs staff who currently work shifts at the port, along with others in the region, are likely to lose their jobs if momentum for change at the port builds, meaning they’ll miss out on any pay increases. However, the best of them will be retained, says Marushevska.

For now, Marushevska says she is doing what she can.

“Of course we’re just at the start of a long road to a complete change in the Odesa customs system, because we’re working with existing procedures and legislation,” said Marushevska. “We’re just using a force of will to change the middle management.”