As the rift between Kyiv and Warsaw widened over the ongoing grain dispute, the existence of Russian grain imports into the EU entered the debate.

At present, Russian agricultural imports are not under EU sanctions, and recently both Ukrainian and Polish officials have called for a ban on Russian grain imports as a potential compromise between the two – Warsaw would call on the EU to introduce a ban on Russian farm imports, and Kyiv would accept restrictions on farm imports into the bloc in return.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Thus, the questions are raised – how much Russian and Ukrainian grain is actually coming into Poland? What about the EU?

In short, the amount of Ukrainian grain imports far surpassed Russian imports, but there has been an extremely drastic decrease in Ukrainian grain throughout 2023 – following the ban in April – that is now on par with pre-full-scale invasion levels.

A recent Kyiv Post Op-Ed covered the grain dispute in detail.

Key findings

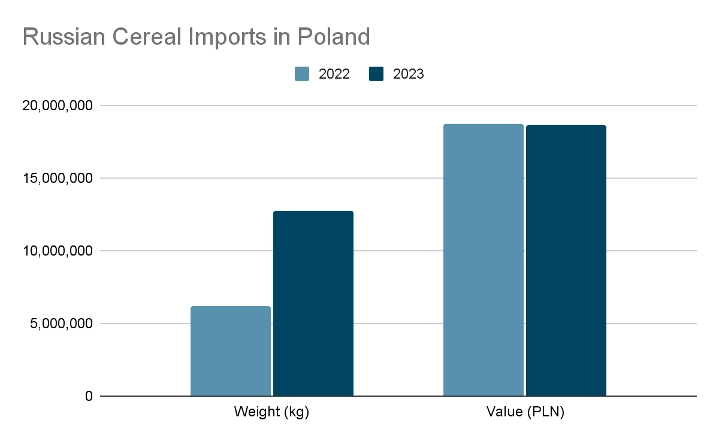

- Poland’s Russian grain imports doubled from 6,140 tonnes [metric tons] in 2022 to 12,694 tonnes in 2023

- Poland’s Ukrainian grain imports halved from 2.4 million tonnes in 2022 to 1 million tonnes in 2023

- Russian grain imports into the EU and Poland are the highest since 2018

- The EU imported 1.5 million tons of Russian grain vs 19 million tonnes of Ukrainian grain in 2023

- Ukrainian grain imports to Poland following the April 2023 ban have largely returned to pre-full-scale invasion levels

- The research cannot take into account grain rejected by third countries and returned to Poland

Russian Grain in Poland

In response to a Kyiv Post inquiry, the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS) provided data on the number of grain imports from Russia and Ukraine.

In 2022, Poland imported 6,140 tonnes of grain – which included buckwheat, corn, sorghum, millet and rice – from Russia, and it rose to approximately 12,694 tonnes in 2023, the highest since 2018.

Putin and Xi Praise Ties, Hours After Trump Sworn In

However, the total monetary value of the imports reduced ever-so-slightly at 18.7 million Polish złoty ($4.75 million) and 18.6 million Polish złoty ($4.73 million) respectively – a mere $20,000 decrease.

Meanwhile, Eurostat’s dataset produces slightly higher figures due to the different categorization methods, where it used the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) instead; it also uses different measurement units (per 100 kg) compared to GUS (per kilogram), which has been considered in Kyiv Post’s conversion. Also, note that a tonne is a metric ton, which is 1,000 kg or 2,204.6 lbs.

Both GUS and Eurostat calculate the figures based on the cargo that crossed the international border and stayed in the country, excluding those destined for other countries (transit); it also does not include cargos being rejected by other countries and sent back to Poland, as those would be counted towards traffic between Poland and those countries.

According to Eurostat’s data, Poland imported 7,659 tonnes of Russian grain in 2022 and 14,430 tonnes in 2023.

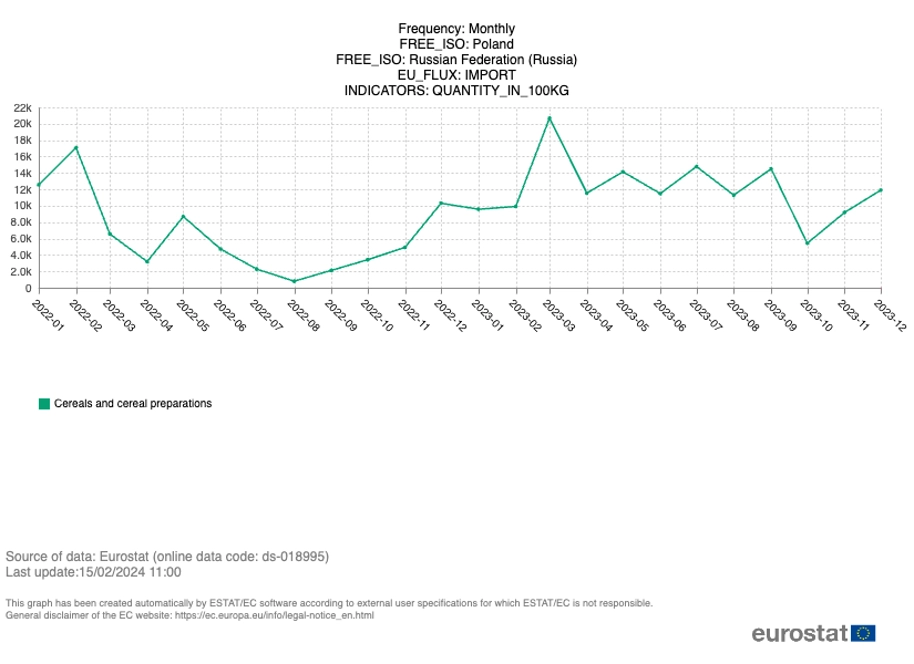

Eurostat data on Russian grain imports per month between 2022 and 2023

Regarding the monthly numbers, there was a spike in February 2022 after the full-scale invasion and another significant spike in March 2023.

Ukrainian Grain in Poland

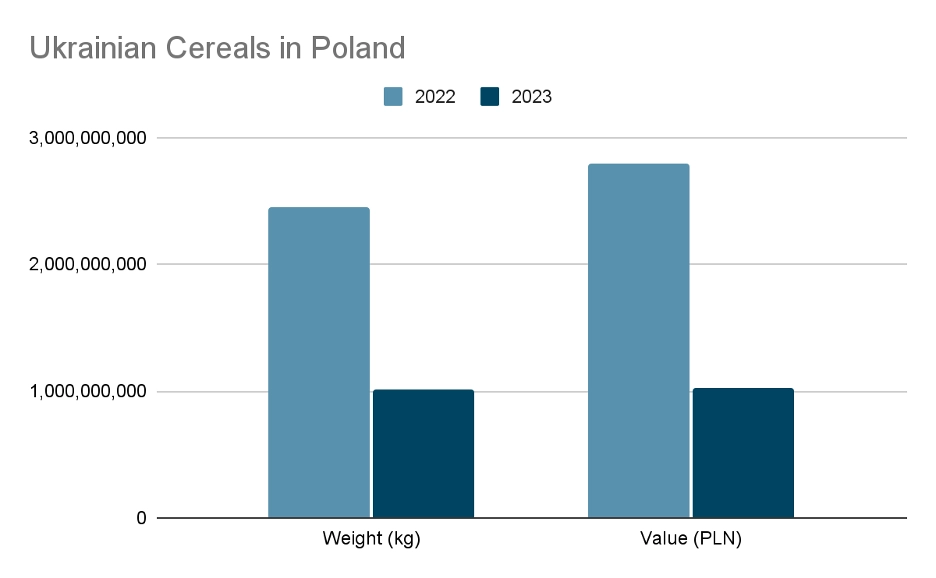

In comparison, Ukrainian grain imports into Poland were more substantial, but there had been a significant decrease between 2022 and 2023 – more than halved.

Polish GUS data showed that 2.4 million tonnes of Ukrainian grain entered Poland in 2022, but the number dropped to 1 million tonnes in 2023.

In terms of monetary values, it also registered a similar decline, going from 2.7 billion Polish złoty ($710 million) to 1 billion Polish złoty ($260 million).

If the numbers are accurate, it would mean that the cost for Russian grain went down from 3 złoty per kilogram in 2022 to 1.4 złoty per kilogram in 2023, whereas Ukrainian grain cost close to 1 złoty per kilogram between the two years.

What about Eurostat’s data?

Similar to Russian imports, Eurostat’s dataset showed a slightly higher number – 27,586 tonnes higher in 2022 and 49,548 tonnes higher in 2023 – compared to its Polish counterpart.

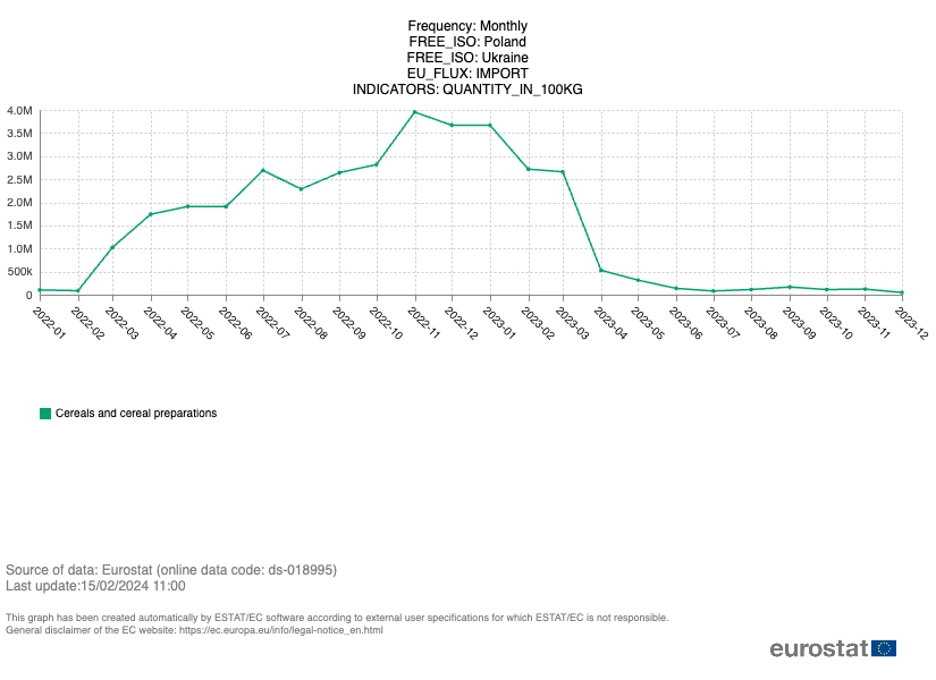

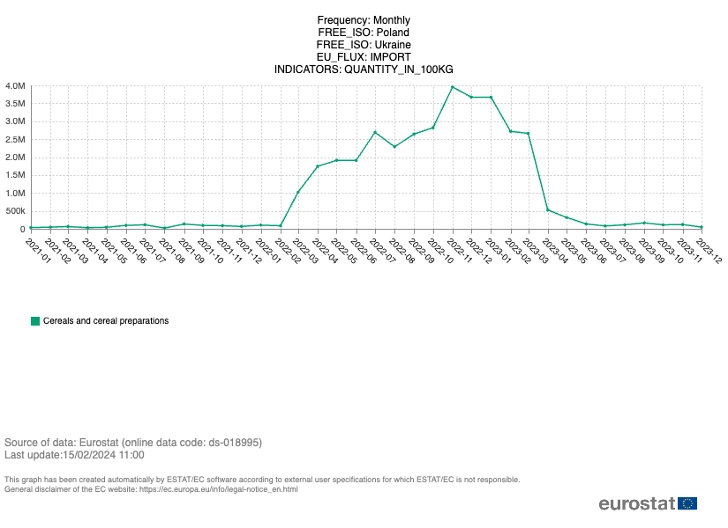

Eurostat data on Ukrainian grain imports per month between 2022 and 2023

Even though the numbers are significantly higher than Russian grain imports and registered a drastic spike in 2022, Ukrainian grain imports did decline tremendously in 2023 after March – following the EU’s temporary ban in May and the ensuing unilateral ban imposed by Warsaw – as demonstrated by the graph above, largely returning to pre-invasion levels.

For comparison, below is a graph from Eurostat that also takes data from 2021 into consideration. In December 2021, two months before the full-scale invasion, 6,670 tonnes of grain were recorded coming from Ukraine into Poland; two years later in 2023, the number was 4,654 tonnes.

Polish farmers began protesting Ukrainian imports in early to mid-2023, but it wasn’t until January 2024 that they began blocking the border with Ukraine.

Russian and Ukrainian grain imports into the EU

Eurostat data said the EU imported 1.5 million tons of grain from Russia in 2023, which is the highest since 2018.

According to a report from Business Insider PL – also using Eurostat’s data – four member states stood out in terms of increased Russian grain imports:

- Estonia: from almost 4,000 tonnes in 2022 to over 31,000 tonnes in 2023

- Spain: from 173,000 tonnes in 2022 to over 256,000 tonnes in 2023

- Italy: from 94,000 tonnes in 2022 to over 473,000 tonnes in 2023

- Latvia: from 265,000 tonnes in 2022 to over 421,500 tonnes in 2023

However, Latvia recently imposed a full ban on Russian agricultural imports in February, becoming the first EU member state to do so.

Meanwhile, Denmark reduced Russian grain imports from 11,000 tonnes in 2021 to only 3.6 tonnes, while Malta went from importing close to 3,300 tonnes in 2022 to zero in 2023.

As for Ukrainian grain imports into the EU, they reached 19 million tonnes in 2023, the highest of all time.

For Poland, it is a matter of livelihood; for Ukraine, it is a matter of survival.

Polish farmers’ requests

Polish farmers’ protests are two-folded – first against the influx of Ukrainian grain, and second against the EU Green Deal, which would see the reduction of pesticide and fertilizer usage in farming by 20 percent by 2030.

The latter point is a complex matter that goes beyond the scope of this article, but it’s one that warrants some attention as it might explain the increased reliance on Russian fertilizers.

As for the former point, it is a difficult question to answer, both factually and morally.

While there have been far-right and pro-Russian elements spotted at the protests, there are still merits to the Polish farmers’ claims.

On the one hand, it is a fact that grain prices dropped tremendously on the Polish market following the influx of Ukrainian grain in 2022 and early 2023 before the ban, which itself came because of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

However, the numbers did appear to show that most Ukrainian grain are merely transiting following the ban, but since it is difficult to determine how much grain were returned by third countries to Poland, there’s no definite proof that fresh imports from Ukraine continue to have an impact on the Polish market.

Mix in the political agenda from different governments – including Moscow’s potential interference – the matter soon grew out of control.

But for Ukraine, a country hailed as the “breadbasket of Europe,” the export through Europe is a lifeline to sustain its economy following the invasion and the subsequent naval blockade imposed by Moscow.

For Poland, it is a matter of livelihood; for Ukraine, it is a matter of survival.

The answer might ultimately lie in finding a mutual understanding beyond the differences, and a form of compromise between the conflict of interests, as demonstrated in the more recent talks between Warsaw and Kyiv officials in creating a mutual export licensing mechanism.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter